Zunar: Malaysia's Brave Cartoonist for Free Expression

Discover how Zunar, an acclaimed Malaysian cartoonist, risks his freedom in the fight for free expression. His courageous art challenges political injustices and censorship in Malaysia.

Discover how Zunar, an acclaimed Malaysian cartoonist, risks his freedom in the fight for free expression. His courageous art challenges political injustices and censorship in Malaysia.

For Zulkiflee S.M. Anwar Ulhaque, the 57-year-old Malaysian cartoonist better known as Zunar, receiving the 2016 Cartooning for Peace Award helped significantly with his protection. “But that’s a very tough question,” he explained carefully, when asked whether such awards really make a difference. “Certainly, it had an incredible impact, particularly because it was given to me by Kofi Annan. This is something that the (Kuala Lumpur) government could not ignore. Nor the fact that the Malaysian public was also very aware of the award.”

In his speech made at the time, Annan, who, as former United Nations Secretary General was also honorary president of the Cartooning for Peace Foundation, noted that through their work both Zunar and his Tanzanian co-winner Gado have reminded us “how fragile liberty remains in Africa and in Asia as well as in other regions of the world.” Through their commitment towards open and transparent societies, he added, they have “received threats in their countries of origin and can no longer practice their profession.” He further pointed out that such artists “confront us with our responsibility to preserve freedom of expression.”

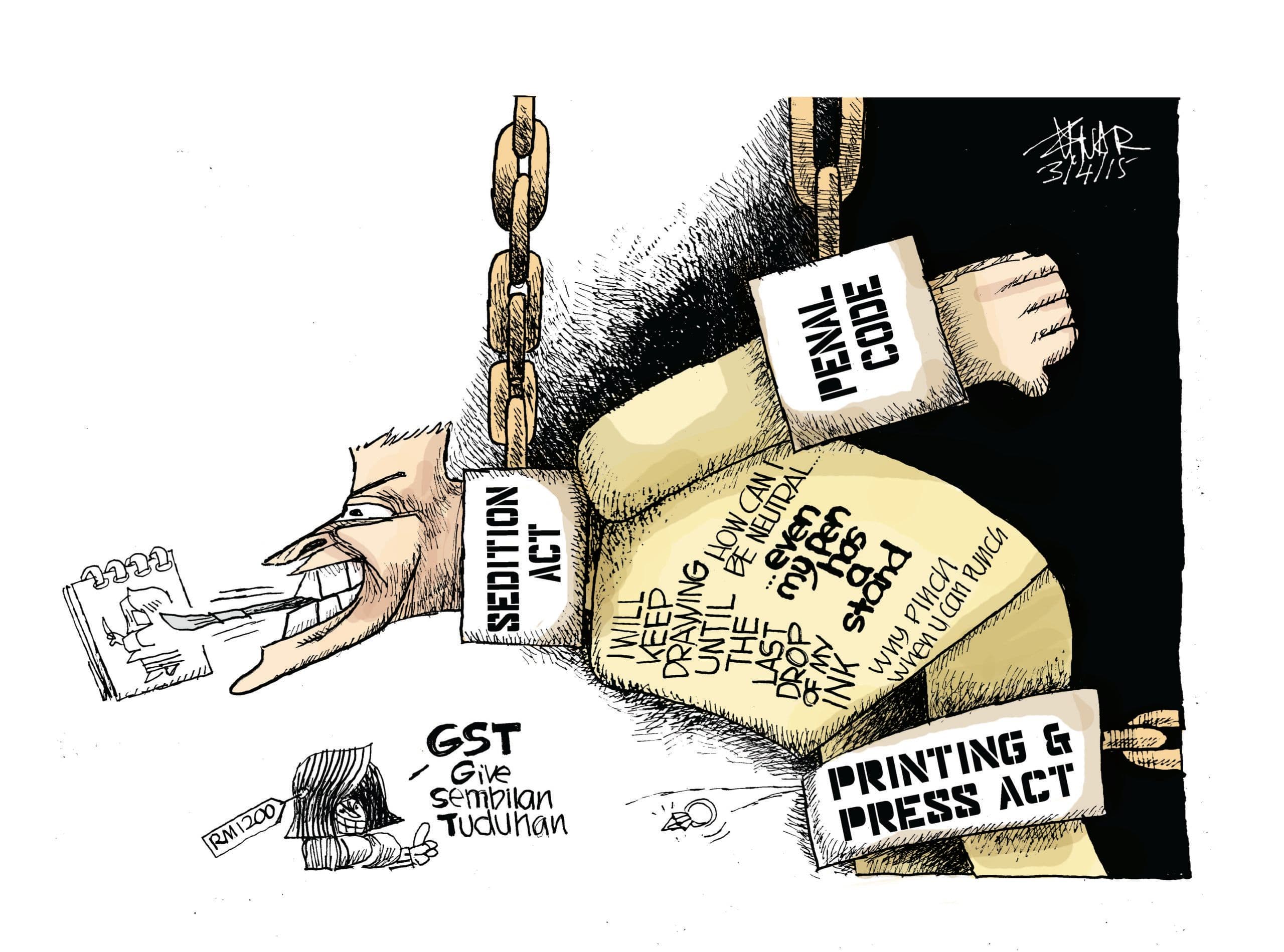

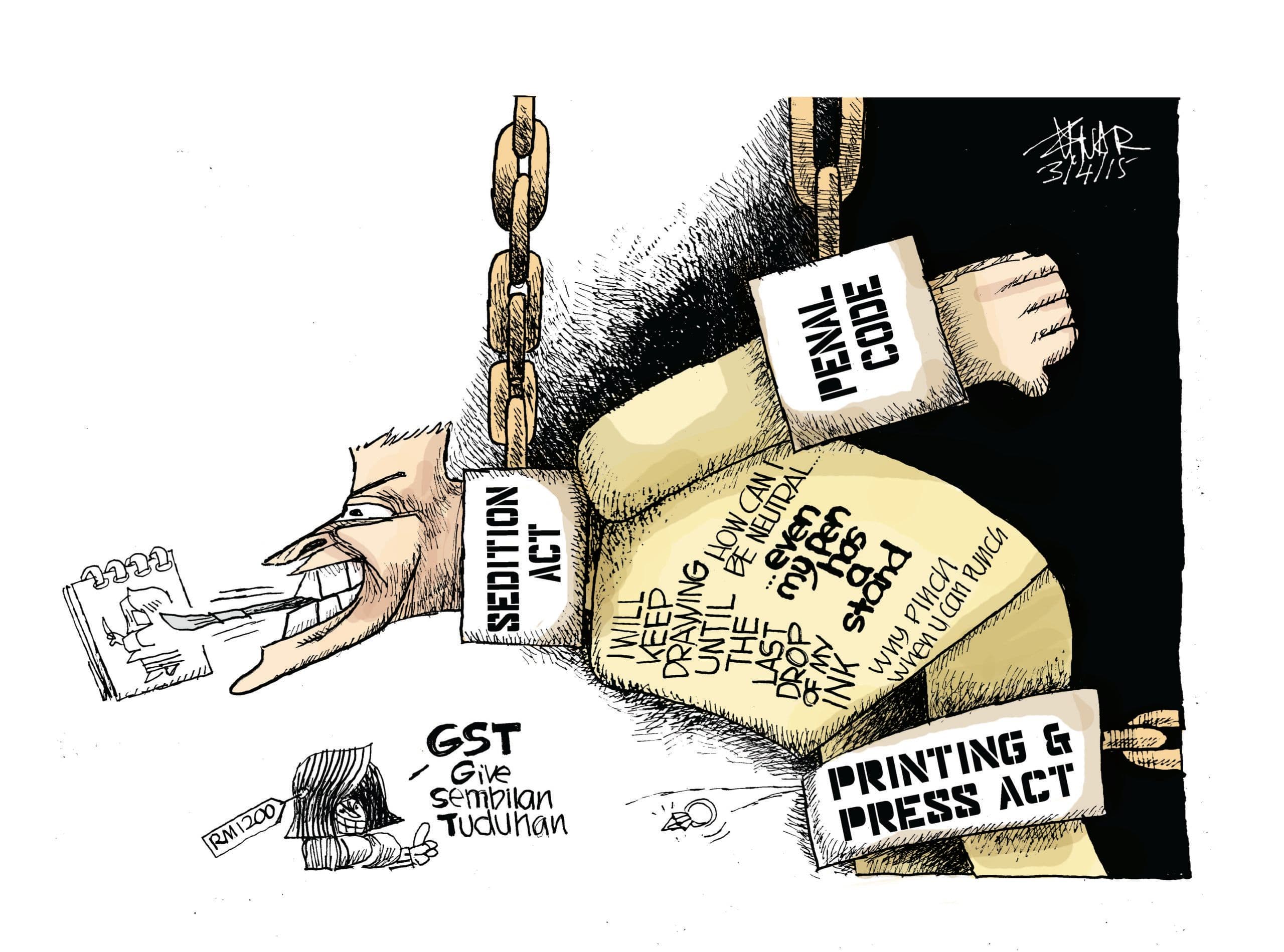

Over nearly four decades, Zunar has established himself as Malaysia’s leading satirist by defying its repressive sedition laws and state-controlled media. His starkly frank cartoons have focused on the corruption and financial scandals that have marked Malaysian politics since independence from Britain in 1963. With the country’s leading newspapers remaining largely silent, the regime of Prime Minister Najib Razaki did everything possible to silence Zunar – and the ridicule he dared to highlight in the name of freedom of expression.

From 2010 onwards, the Najib government repeatedly arrested Zunar, or raided his office and home. It banned nine of his books as well as his online activities, plus confiscated thousands of copies of his publications. They also intimidated his three main distributors with removal of their licenses if they continued to sell his works. Charging Zunar under six different laws, plus nine charges of sedition, the authorities threatened him with 43 years imprisonment, primarily for lambasting both Najib and his wife, Rosmah Mansor, for their illicit activities or public absurdities. This included a series of tweets made in 2015 criticizing the regime. They also banned him from overseas travel.

Given the enormous prestige of the Cartooning for Peace award, however, and the embarrassment that it might cause, Najib was forced to allow Zunar to fly to Geneva to receive the prize and to open a lake-side exhibition of satirical cartoons. “Such top events can really bring such regimes under a lot of pressure,” Zunar added with a smile. Both Najib and his wife Rosnah are themselves now facing major corruption and theft charges and are prevented from travelling.

Zunar, who was only 18 when his first cartoon was banned (he had criticized a teacher in his school magazine), had a particular passion for focusing his satire on Rosmah, whom he regarded as a ‘gift’ to any imaginative cartoonist with her massive hair-do’s, obsession for luxury goods and expensive lifestyle. His drawings made her a source of national ridicule.

Since the defeat of Najib and his Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition, which ruled the country for over 60 years, freedom of expression has become easier. “The charges against me have been dropped and I am now able to draw whatever I like. You can also find my publications in the shops or at news stands, which makes a big difference because this is the way I make my living,” Zunar explains.

At the same time, he maintains, the statutes haven’t changed. While the Alliance for Hope (PH, or Pakatan Harapan) government of Maharhir Mohamad has pledged a new era of freedom of expression, Zunar is not so sure. “How can we say the situation has improved if the laws remain? The knife is still there. They are still on the books, so (technically) the whole thing could start again.”

According to the cartoonist, a new danger is emerging, notably a brutish form of nationalistic racism and extremist Islamic-inspired discrimination that is increasingly marking BN opposition ranks. This is now specifically targeting the more ethnically and religiously mixed Alliance of Hope government, which includes Malay, Chinese, Indian, Hindu and other political or religious groups.

“This is what I am now drawing against. People are being attacked for not being Malay enough. The former government is encouraging a new form of intolerance,” Zunar maintains. “We have to speak out.” Once when the police arrested him, he told them that they could “ban his cartoons but not his mind.”

For Zunar, cartooning is an important way to ring the ‘alarum bells’ as it can communicate with everyone, regardless of language and including those who can’t read. “This is why politicians hate cartoonists. They dislike being cancelled out. They also know that we can make people laugh and across all lines,” he adds. Humour is a highly critical form of expression for cartooning, he explains. “It is important for everyone to laugh at governments, preventing politicians from taking themselves too seriously. My way of protesting is by laughing and making people laugh.”

At the same time, he notes, it is vital for people to understand the dangers. The politicians can use any form of manipulation or lies to inspire hate – and intolerance. “When governments ban books, they can use any definition they want to say that you are being a threat. If they don’t like you, they can get you,” Zunar argues. “So, in the end, I don’t see any real change.”

Zunar, who has always refused to back down or to remain silent, sees a particularly heinous threat with the rise of the supposedly “new Malay” identity. As he explains, 60 per cent of his country’s citizens are ethnic Malay with 30 per cent Chinese and 10 per cent all the rest, including people of Indian, Pakistani, Indonesian, Tamil, Thai and European origin. So one is beginning to witness a form of ‘us’ (ie. Malay) against ‘them’, all the rest, he says. In addition, there is the emergence of a Muslim against non-Muslim approach. Most of the new political opposition is both nationalist Malay and hardline Islam.

“This is terrible for Malaysia and terrible for everyone,” says Zunar, who is himself both Malay and Muslim. “So I consider it my role to speak out. It is also our responsibility as a people.”

Global Geneva editor Edward Girardet is both a foreign correspondent and an author. He is based in Geneva and Bangkok.

Teach your children well…Democracy today?

Chappatte and the stifling of graphic satire – 2020 Geneva Foundation Laureate

Jeff Danziger – A cartoonist on the political frontline

World Press Freedom Day, 3 May 2019

Launch of Global Geneva’s Young Journalists’ & Writers’ Programme and Awards for international schools

Helping young people to trust journalism – and counter fake news

International Geneva: Not just a hub but a global reality