Explore the Seine: Paris's Most Romantic Journey

Embark on a journey along the Seine River, Paris’s most romantic waterway known for its breathtaking views and rich history. Explore things to do and the best Paris cruises!

Embark on a journey along the Seine River, Paris’s most romantic waterway known for its breathtaking views and rich history. Explore things to do and the best Paris cruises!

One of my favourite words in French is “partage,” sharing. I love to share stories and open conversations with others. So I decided to write a book about a subject that gave me joy and would give me the chance to spread that joy to readers.

When I was a very young and very green foreign correspondent in Paris for Newsweek years ago, the Seine made me happy. I had been living in Chicago and there had been a husband there, but he announced one day that he was leaving. I arrived in Paris with no friends, no lovers, no sources, mediocre French and a broken heart. Most evenings I crossed the river during my walk from the office on the Right Bank to my apartment on the Left Bank. Along the way I stood on the Pont de l’Alma and watched the sun set on the river behind the Eiffel Tower. Pure magic! I could never be lonely on the Seine. The river allowed me to begin a journey of discovery—of Paris, of the French people, of myself. Its energy pumped deep into my veins; its light gave me strength.

I came to Paris again in 2002 as Bureau Chief for The New York Times with my husband Andrew (we met on a train in 1984!) and our two daughters. Over time, I decided the time had come to make the river mine and explore it all along its 777-kilometer route. The result is a deeply personal book shaped by my impressions of life on the river. I have told the stories that resonated with me and shared encounters with people whose lives touched me.

Here is a passage from the book that sums it up:

“The Seine is the most romantic river in the world. She encourages us to dream, to linger, to flirt, to fall in love, or to at least fantasize that falling in love is possible. The light bouncing off her banks and bridges at night can carry even the least imaginative of us into flights of fancy. No other river comes close. The Ganges, the Mississippi, and the Yangtze? They are muscular workhorses. The Danube? It may be immortalized as the world’s most recognizable waltz, but its history is one of warring nations and tribes. The Thames? Who can name one famous couple who fell in love on its banks?”

I suppose I could have written a book about diplomacy or the Middle East. But that was my old life. In 1990 I wrote a book about Iraq. Nearly ten years later I wrote a book about Iran. A war book? I am proud to have been among the first group of female foreign correspondents to work in war zones in the Middle East. And yes, in the 1980s I covered the Iran-Iraq war from both sides of the border and the war in Lebanon. I was locked in a room by Colonel Kaddafi of Libya when the interview was over. I was put into a prison in Syria (just for a day). I walked through minefields in Iran. When I became a mother, I decided never again to put on a flak jacket and a helmet.

Here’s a passage I wrote in my last book, The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue des Martyrs about my closest encounter with death in a war zone.

“In the fall of 1983. President Ronald Reagan had sent the marines to help calm Lebanon’s civil war. I was a roving international correspondent for Newsweek. The Beirut bureau needed reinforcements.

“The fighting was so intense that the Beirut airport was closed. The only way to get into the country was to sneak in: relatively safely by ferry across the Mediterranean from Cyprus or dangerously by car overland from Israel. I am subject to motion sickness. Not just ordinary motion sickness but the debilitating kind that keeps me off every ride at an amusement park. “Traveling on a slow-moving aircraft carrier requires massive doses of Dramamine. Swinging on a swing? Torture. An all-day ferry ride over the choppy Mediterranean? Never.

I flew into Tel Aviv, hired an Israeli driver, crossed the border into Lebanon with an American passport and no visa, hired an Arab driver, and headed north. Somewhere outside of Sidon, on the road to Beirut, the shelling started. I had no idea what the target was, or if there was a target. But shells were landing on both sides of a desolate road, so close that the smell of explosives filled our lungs. “The driver wanted to turn back. I refused. This was long before cell phones. I had no way to communicate with the outside world. I mentally took stock of the situation: I work for a weekly news organization and no one is waiting to hear from me. I’m going to die with this panicked driver; vultures will attack my corpse before anyone knows I’m dead.

“At that moment I thought of Saul on the road to Damascus. And I made a pact with the Almighty. “God,” I said, “If you get me out of this, I’ll believe!” (If truth be told, I said, “I’ll try hard to believe.”)

“A few hours later I was in Beirut, in a comfortable room in the Commodore Hotel, where foreign journalists stayed. Shortly after I left, suicide bombers blew up buildings housing American and French military forces, leaving 299 people dead. I had been at the American barracks just days before. Maybe God was looking out for me. After that, I was trapped. I had promised God I would believe. I was superstitious and Sicilian enough to know that I had to keep my promise.”

A different era, no? Now is the time to share my adventures on the most romantic river in the world!

Elaine Sciolino has lived in Paris with her husband since 2002. Her first book on Paris is the New York Times bestseller: “The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue des Martyrs.” Other books include: “The Outlaw State” (1991); “Persian Mirrors: The Elusive State of Iran” (2000); “La Seduction: How the French play the game of life” (2011).

For book order details, please see the following links:

Amazon. Barnes & Noble or Indiebound

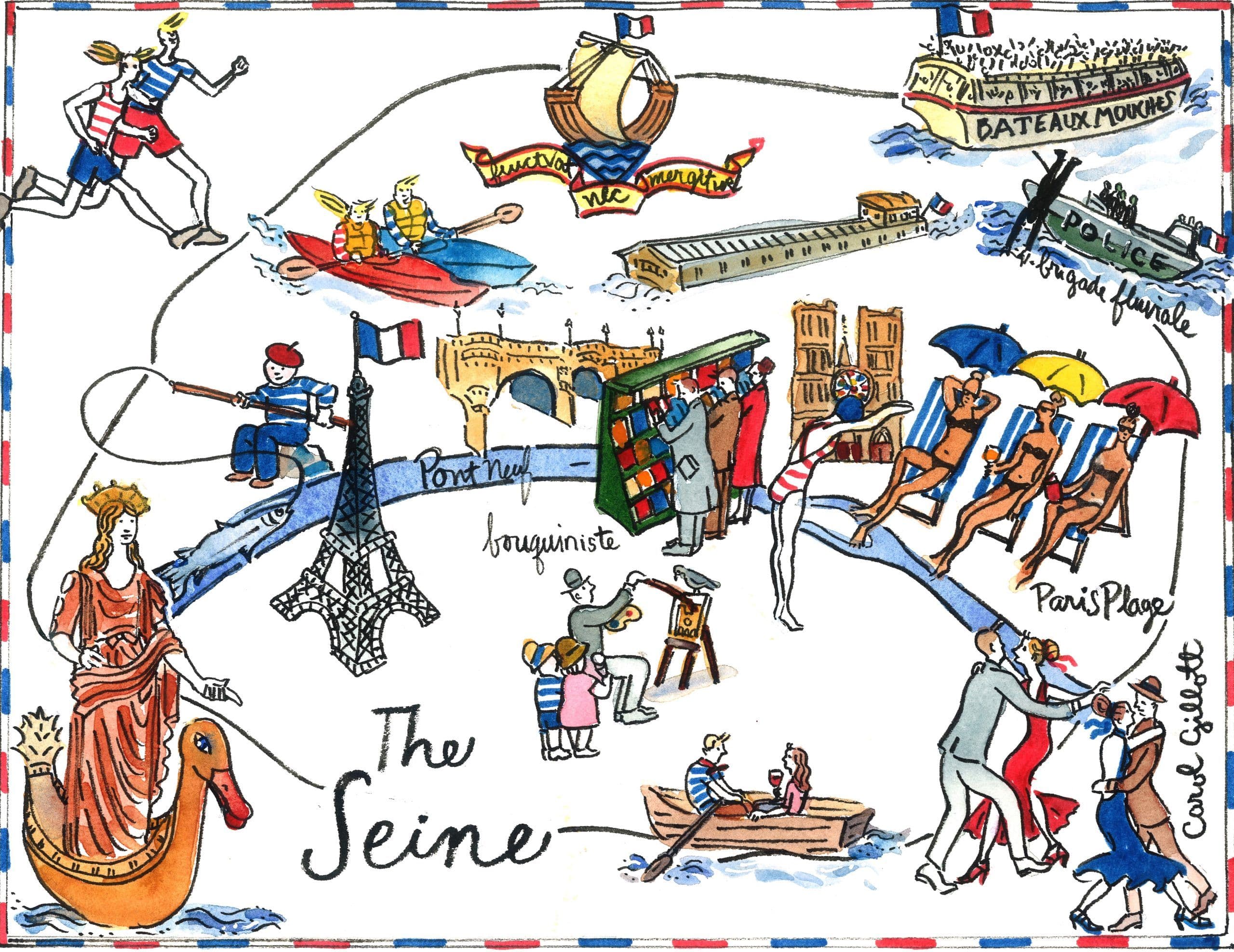

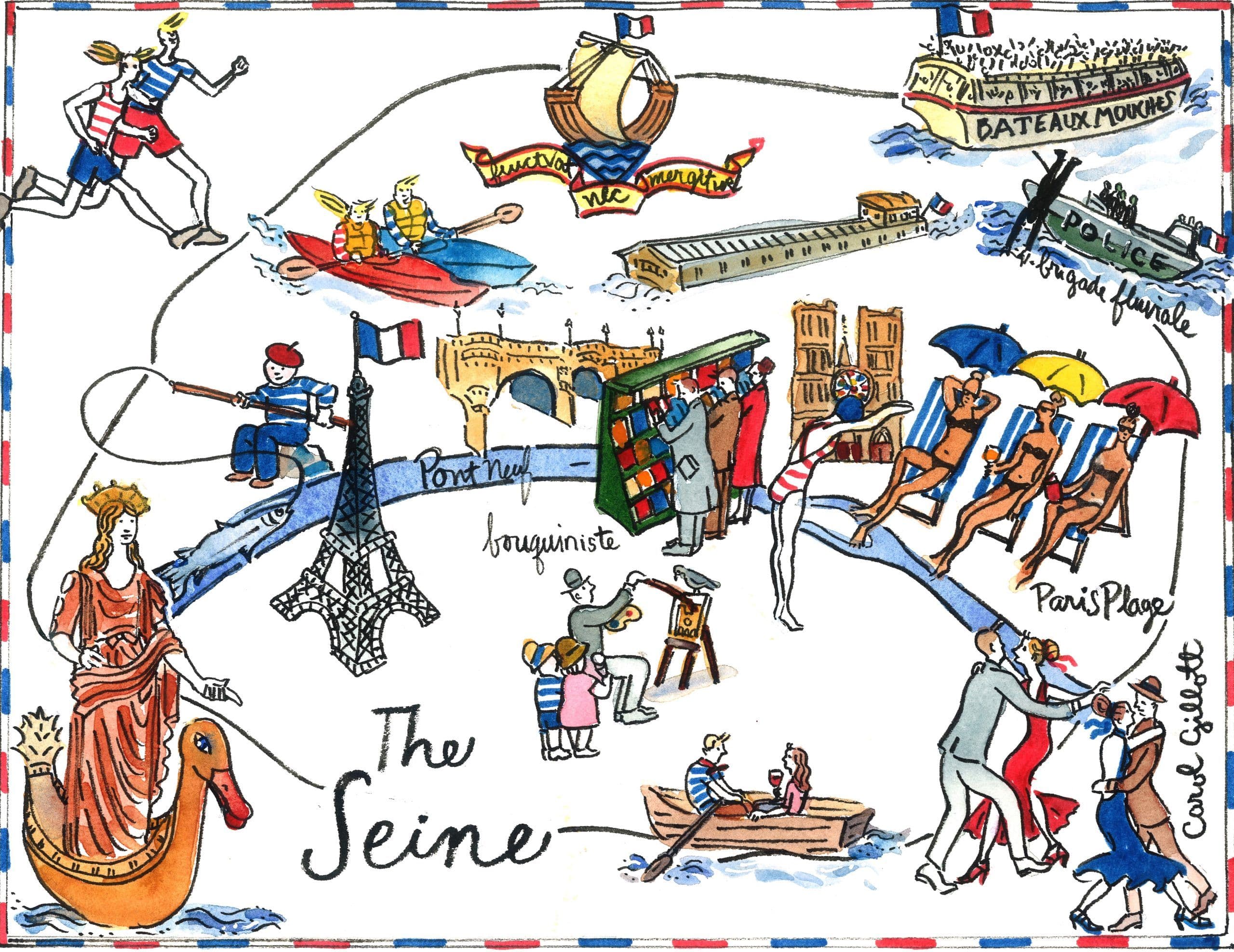

Life is lived on the river—on barges, pleasure craft, pontoon platforms, decommissioned naval vessels. Afloat on the Seine, you can live, eat and drink, make love, get married, practice yoga, run a business, shop for books, watch fireworks, do a wine tasting, go fishing, dance the tango. You can attend a fashion show, a concert, a play. You can find a hotel, a psychiatric hospital ward, a film studio, a homeless shelter, an architect’s showroom—all floating on the river….

The Seine has been a source of food and water, an irrigator of crops, and a healer. It has been a killer, a crime scene, and a burial ground. It has been a sewer and waste dump for towns and cities, farmers and factory owners, tanners and butchers, washerwomen and bargemen. It has been an attack route in war, a promenade in peace, and a starting point for global exploration. It has been a practical powerhouse for industry and a path of transit, ferrying foods across its currents. Finally, it has been the keeper of the secrets of French history….

The river starts as pure spring water, bubbling up from fissures in an obscure plain in northeast Burgundy. From there, it flows west, cutting a deep trench through the dry chalk plateau of Champagne country and the medieval city of Troyes. It swells as it absorbs other waterways, showing off and then abandoning different landscapes on its banks: cultivated fields, dark green thickets, dense woods, spongy marshes, grassy meadows, white limestone cliffs speckled with black flint. A children’s geography book from 1926 describes the Seine as the “most regular and most navigable” river in France, with a gentle drop along its route—only 1,465 feet until it heads triumphantly into Paris almost midway on its journey. At the city’s far western edge, it becomes lazy and winding, looping and twisting and losing its sense of direction as it continues a northwesterly course across the flat country of Normandy. At Rouen, about seventy-five miles northwest of Paris, it becomes a maritime river, deep and wide enough for oceangoing ships. Fifty-six miles farther along, it opens to a large estuary, a huge expanse of water that acts as a transition zone between the river and the sea. At the end of the estuary, the Seine empties into the English Channel at Le Havre….

I had come to Paris to find happiness and freedom. It was in Paris—not in Tokyo or London or Hong Kong—that I had deposited my dreams. It was Paris that carried me along and stayed with me. I had healed in Paris after a failed marriage, traveled as a foreign correspondent from Paris to faraway places, and had fallen in and out of love in Paris. Years later, I shared a life with my husband and two daughters in Paris.

The river that created Paris is not long. But it has carried me to new worlds and seduced me with its history, culture, and beauty. I have watched the seasons from its banks and bridges: the pink, cone-shaped blossoms of the horse chestnut trees in April; the long, hot July days that refuse to end before ten p.m.; the fickleness of October, when the weather changes half a dozen times in as many hours; the damp, gray, short days of December.

Julien Green, in The Strange River, a novel of sadness and loss published in French in 1932, gives a human voice to the Seine. “I am the road running through Paris,” says the river. “I have carried off many images since you were a child and reflected many clouds. I am changeable, but as people are. . . . We have something in common, you everlasting passersby and I, the fleeing water, which is that we never go back: your time is my space.”

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who lived in the sixth and fifth centuries b.c., put it slightly differently: “You can never step in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and you are not same person.”

That is the secret of the Seine. It is forever changing—widening, deepening, reflecting, twisting, shriveling from too little rain, overflowing its banks. But it always moves forward.

As, I hope, do I.

One Man’s War for Human Dignity: The Extraordinary Life of Kevin Boyle

Swiss Journeys: A weekend in the Valais – culture, vineyards and thermal baths

Switzerland’s Prisoners of War during two world wars and beyond.

Book Reviews: Editor’s selection – Expat writers, Syrian refugees and exiles

Swiss Journeys: Neuchâtel – combining nature and culture (Part I)

Dinners with Graham Greene

The Capital of Civilization: Brexit, populism and the 150th anniversary of the Siege of Paris