Peter Jouvenal: Insights from His Taliban Incarceration

Peter Jouvenal shares his experiences of incarceration by the Taliban, illuminating the complexities of press freedom and human rights in Afghanistan.

Peter Jouvenal shares his experiences of incarceration by the Taliban, illuminating the complexities of press freedom and human rights in Afghanistan.

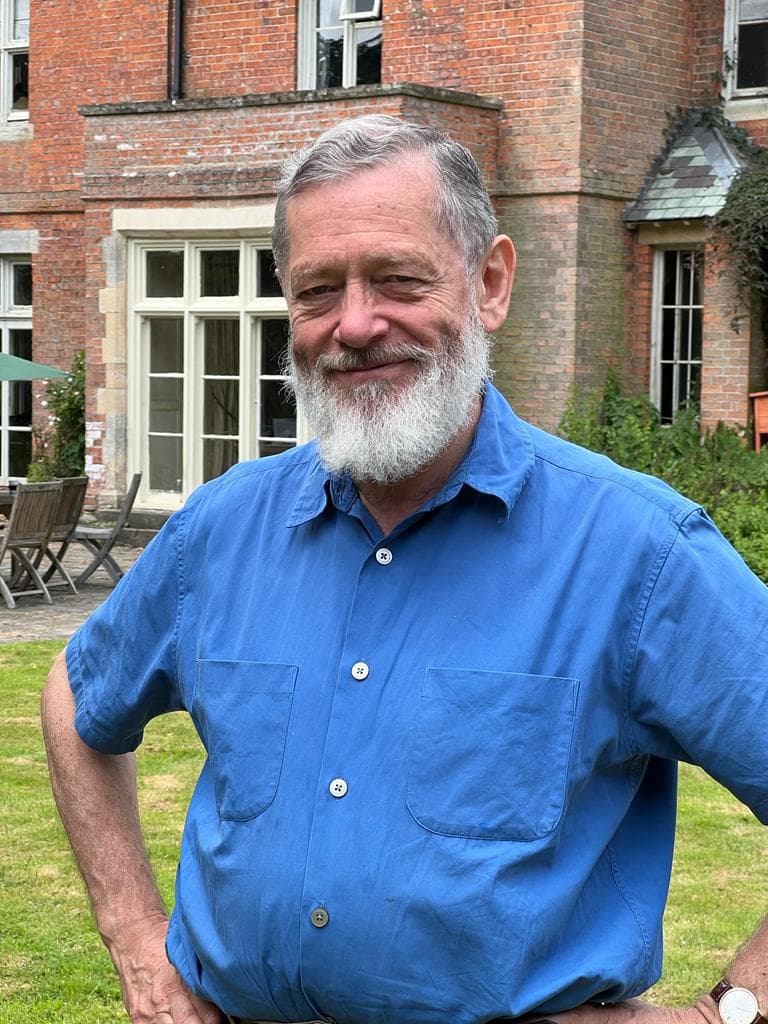

Now back in the United Kingdom with his Afghan wife and three daughters, Peter Jouvenal shows few signs of his six months incarceration by the Taliban. Smiling and confident, Jouvenal, 64, sports a full, grey-speckled beard as he talks from his home in Lincolnshire, just north of London. “There is no point in being bitter,” Jouvenal notes. “It was a typical Afghan situation. Things take a long time. For me, the worst was the boredom, basically a waste of time.” (See BBC Television interview with Peter Jouvenal Wednesday July 6, 2022)

Jouvenal, who also holds a German passport, has spent more than four decades in and out of Afghanistan, much of the time reporting as a cameraman-producer for the BBC, CNN, NBC, ZDF along with other major broadcast news networks. Jouvenal has also specialized in conflicts such as Somalia, Liberia, the Balkans, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, the two Gulf Wars and elsewhere. Many Afghan experts and scholars, including American development and military specialists, have long regarded Jouvenal as one of the most insightful western journalists to have worked in the country. He is also widely known amongst the international community as the co-founder of Gandamack Lodge in Kabul, a highly popular hotel frequented by reporters, aid workers and diplomats.

“The Taliban treated us well, not much different from the sort of hospitality the mujahideen (holy warriors or guerrillas) used to provide when we covered the Soviet war, or ordinary Afghans when they invite you into their homes,” said Jouvenal. “I don’t think that I’m suffering from Stockholm Syndrome,” he added with a laugh. “And if I’m to suffer from PTSD, it’s probably because I had to read Harry Potter three times. We had very little to read.”

Based on personal experience, Jouvenal compared his detention by the Taliban with the poor treatment he received when arrested by the Western-backed Hamid Karzai regime. Jouvenal was held on trumped-up charges following his work to help obtain the release of three kidnapped United Nations Volunteers (UNV). The Ministry of Interior wanted him to pay a bribe which he refused and he was locked up for two weeks. The Karzai government was forced to release him, largely because of criticism by the international press and aid community. Jouvenal was also instrumental in obtaining the release of 27 Pakistanis fighting with the Taliban and captured by the Northern Alliance following the events of 9/11. Similarly, he negotiated the release of a British national who had also joined the Taliban and was held by government forces for five years.

Jouvenal, who converted to Islam two decades ago, makes it clear that he is not pro-Taliban, but rather pro-Afghanistan. “My main concern is what is happening to the Afghan people,” he maintains. “I have known this country for a long time with different regimes, but you have to see things in context. This is something westerners often have difficulty understanding.” The problem, he added, is that for decades everyone has made a mess of Afghanistan from the Americans and Russians to Al Qaeda – and Afghans themselves. “Over the past 20 years, many involved with Afghanistan have been there for their own benefit and not that of ordinary Afghans.” (See Oslo Peace Awards Essay on Afghanistan by Peter Jouvenal and Edward Girardet, July, 2021)

“The previous Ashraf Ghani government supported by the West was incredibly corrupt, and we all knew it. So was much of the international community. (According to international observers, Ghani received barely received 900,000 votes in the 2019 general elections with less than 20 percent voter turnout and despite efforts to manipulate the results in his favour). The Taliban lack the necessary skills and are faction-ridden. No one knows what the other hand is doing. That’s probably the main reason why we were held prisoner for so long. No one could make a decision even though at least seven government ministers were pushing for our release because of my background or because someone knew me. They fully realized that our continued detention was not good for business or for obtaining international support and recognition, something the educated Taliban realize is crucial.”

Following his arrest, Jouvenal’s case was taken up by a rapidly growing group of friends and colleagues to put pressure on western governments, particularly the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), but also the Taliban, to seek his release. The FCDO did so from behind the scenes in Doha as did some US State Department officials even though he is not a US citizen. Even the German government stepped in to help. An online petition collected more than 110,000 signatures. Students from the University of Maine School of Law filed an official complaint with the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. The support by all these groups and individuals, notably the UK-based Hostages International, proved exceptionally helpful, Jouvenal stressed.

Surprisingly, Jouvenal reported that there had been very little assistance from the United Nations in Kabul and Geneva or from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The ICRC never managed to visit Jouvenal or the others in detention. According to a number of journalists, Jouvenal had often helped these two organizations obtain prisoner releases in the past, yet requests for these organizations to provide assistance were either ignored or politely refused.

Since I last chatted with Jouvenal in November 2021 several weeks prior to his arrest, he seemed little changed. If anything, he had put on weight, primarily, he maintained, from too much food and not enough exercise. He was incarcerated in a jail formerly established by the KHAD, Afghanistan’s KGB-style police during the communist period of the 1980s. It was then used by different governments since. Ironically, the prison lies in the prestigious Shar-e-Now district next to the Iranian embassy and almost opposite from where Gandamack was once located.

According to Jouvenal, the Taliban treated them well. “From the first day onwards, the guards brought us blankets, mattresses and the heater from their own room,” he said. “The cells, which had been left over from the previous regime, were cold, damp and with no electricity, very basic. The Taliban renovated everything, equipping each room with an electrical outlet and provided heaters.” For the next few weeks, conditions remained spartan but steadily improved. “Our cells were basic but the prison director, whom I got to know well, even put in a hot water system so that we could have warm showers.”

The cell cameras, a layover from the previous western-backed government, were initially fixed, but then, following a visit by a delegation of Koranic scholars, it was decided that being able to watch inmates urinating in a bottle at night was not considered Islamically ‘appropriate’. The cameras were switched off, but a guard was placed 24 hours a day on the same floor to watch over the prisoners.

Such improvements were apparently carried out under orders of Abdul Haq Wasiq, a former Guantánamo Bay detainee from 2002 to 2014, who is now head of the Taliban’s General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) in Kabul and is believed to have been initially responsible for Jouvenal’s arrest. “I had expected to be put into an orange jumpsuit and treated badly,” said Jouvenal, “but Wasiq had sworn that his men would never treat prisoners in the same manner as the Americans did at Guantánamo. So while we had to deal with the tedium of waiting, we couldn’t really complain. That’s just one of the things about working in Afghanistan.”

Such claims stand out in stark contrast to the assertions made by Afghan-American naval reservist Safi Rauf, who was detained in the same location for 105 days together with his brother, Anees Khali. They were released in early April 2022 following negotiations between the Americans and the Taliban in Doha. Rauf had claimed that they were held in complete isolation, tortured, and denied proper bedding and other comforts, which Jouvenal maintains is not correct.

“We were all held in the same place,” he explained carefully. The prisoners were indeed held in isolation, two to a cell, he said, but it did not seem to occur to the Taliban that they needed exercise. This was granted – half an hour a day – at the prisoners’ request. The inmates were also permitted lavatory visits four times a day with a bottle provided for urinating at night when they could not be escorted out. The Taliban acceded to all their demands except the right to watch television or listen to the radio. Information-wise, the prisoners were cut off from the outside world.

“In reality, we were very comfortable,” Jouvenal said. “I know that’s not what people would like to hear, but I think it’s important to give Wasiq his due for seeking to treat prisoners according to the Koran. If we don’t say this, then they may not be so nice with future inmates.”

Jouvenal maintained that he could only comment on what he had experienced in the prison where he was being held and not other known detention centres, such as the East German-built Pul-e-Charkhi prison outside Kabul. He also said that he knew of only one torture incident. This was against a fellow British intern who was accused of being a spy and beaten on his feet. The Taliban wanted to know about surreptitious images on his mobile phone. When it turned out that these had been downloaded from a Taliban website, the jailers stopped the beatings.

As for meals, they were far better fed than most Afghans, many of whom are on the verge of starvation. “We were given regular Afghan-style meals with varied menus including warm, fresh nan (unleavened bread) as well as meat and vegetables,” he said. “It was almost embarrassing.” According to Jouvenal, the freed American naval reservist and his brother had received special attention, possibly because of their American connections. They were regularly brought food packages, such as fresh oranges. These Rauf rarely shared, which did not endear him with the other prisoners. According to Jouvenal, Rauf had even insisted on taking back a copy of Les Misérables, one of the few books available, when the two were released.

While Jouvenal still does some work in journalism, he has more recently focused on business. It was this that got him arrested. In autumn, 2021, barely three months after the West’s precipitous pull-out from Kabul followed by the Taliban takeover in mid-August, he decided to return to Afghanistan. The main reason, he notes, was to check on Afghan friends, including former employees and their families of his wife Hassina Syed, who was named Afghan Businesswoman of the Year and one of the World Economic Forum’s Young Leaders of Tomorrow. Hassina was one of thousands of Afghans evacuated by American, British and other NATO forces at the last minute. (See Gunilla von Hall of Svenska Dagbladet article in Global Insights on Hassina Syed)

At the same time, Jouvenal wished to explore possible mining investments. In the days prior to his arrest, Jouvenal openly met with Talib officials, including the Minister of Commerce and Industry who provided him with a letter granting permission to work in Afghanistan. Hence Jouvenal’s surprise at being arrested given that he had an visa and official letters of introduction.

Together with another Westerner (names of the other prisoners are being withheld), Jouvenal was detained on Saturday morning December 13, 2021, by a group of armed Taliban who suspected them of being spies. A local resident had reported them when he saw two foreigners – one of them taking photographs with his mobile phone – wandering around the abandoned former British Embassy residence in the upmarket Wazir Akbar Khan part of Kabul.

According to Jouvenal, they were – in fact – house viewing for a place to rent. The residence gate was open and several local Afghans had invited them in. But it also looked as if the building was being prepared for a meeting later that day. The fact, too, that it was located only a few hundred metres from a GDI office probably did not help, Jouvenal admits. Since taking power in August 2021, according to human rights sources, the GDI has arrested hundreds of Afghans, Pakistanis and other foreigners suspected of being spies, insurgents, traffickers and ISI operatives.

Jouvenal and his colleagues were eventually taken to the prison, where they were all kept in the basement in 3×3 metre cells with a light that was on 24 hours. “We could have it turned off, but the switch was on the outside. Some of the other prisoners had theirs switched off at 10 in the evening but we had ours on the whole time as you could then see if you wanted to urinate.”

During the first two months, the Taliban sought to implicate Jouvenal and his fellow inmate under select charges, such as working for MI6, Pakistan’s powerful military intelligence agency, ISI, or helping the Panjshiri resistance revolt against the new regime. They also accused him of being part of Al Qaeda based on an internet photograph depicting American journalist Peter Bergen and Jouvenal with Osama Bin Laden during a 1996 CNN interview. “They constantly came up with different allegations, but then finally accepted that they couldn’t prove anything because we had done nothing wrong.”

As a journalist, Jouvenal has always cultivated contacts with all sides. He was one of the few outsiders to warn the Americans and their NATO allies not to ostracize the Taliban following their ousting in the fall of 2001. Whether one liked it or not, he pointed out, the Taliban still represented a significant portion of the Afghan people. Without making them part of the political process, he warned, there will never be peace in Afghanistan. “Just because they may appear to have lost, the Taliban are still there.”

As far as Jouvenal is concerned, the West needs to become far more realistic with its Afghan dealings. (See Vanni Cappeli oped) “This is what the Afghan people deserve,” he argued. “They cannot simply be abandoned. The West has an obligation. The recent earthquake is only one example.” This does not mean kowtowing to the Taliban, he noted. The West can only provoke genuine change by engaging. So what are Jouvenal’s next steps? “My wife and I plan to return to Kabul. But probably with all the right permissions, including the consent of my new friends at GDI,” he said with a smile. Apparently his former jailers have agreed to provide him with the necessary papers.

Edward Girardet is a foreign correspondent, author and editor of the Geneva-based Global Insights Magazine. He has covered wars and humanitarian crises worldwide for The Christian Science Monitor, US News and World Report and the PBS Newshour. His books include: “Afghanistan: The Soviet War”; “Killing the Cranes – A reporter’s journey through three decades of war in Afghanistan”; “The Essential Field Guide to Afghanistan”. (4 fully-revised editions) and “Somalia, Rwanda and Beyond.” Girardet is currently working on a new book, The American Club: The Hippy Trail, Peshawar Tales and the Road to Kabul.

Editorial Note: The fourth, fully-revised edition of ‘The Essential Field Guide to Afghanistan’ published by Crosslines Essential Media, a partner of Global Geneva Group, was printed in 2014. Much of it is still relevant. You can procure an e-edition through this LINK on Amazon. We still have a few hard copies left, too. You can order with: editor@global-geneva.com Cost: 50.00 CHF/USD including p&p. If you like our independent journalism in the public interest, you can also donate. We urgently need your support to help fund our reporting.

America’s – and NATO’s – Afghanistan disaster: Still a possible peace solution with a Marshall Plan.

Not Knowing the Color of the Sky in Afghanistan

Ukraine: Putin’s Vietnam

Focus on Afghanistan: Peter Jouvenal – A journalist veteran held by the Taliban

Back to the Cold War

Russia’s Ukraine Intervention: Death by a Thousand Cuts?

Russia and China: The Bros in the Owner’s Box

Building Bridges for Geneva and the world: Breaking the silos