Explore Bobsled Diplomacy: An Adventure in Geneva

Experience the thrill of bobsled diplomacy in Geneva, where international collaboration meets adventure sports. Learn how this unique experience fosters cultural exchange.

Experience the thrill of bobsled diplomacy in Geneva, where international collaboration meets adventure sports. Learn how this unique experience fosters cultural exchange.

It was the beginning of December and too early in the season to ski, so I looked around the Swiss resort for something to do. “Why don’t you take a look at St Moritz’s Olympic bobsled run?” the hotel concierge suggested.

When a Swiss-German chap at the top of the Cresta Run saw me walking over in my suit and tie, overcoat and low city shoes, he grinned at his comrades and exchanged a few words in incomprehensible “schwyzertütsch,” and said to me, “Care to take a ride?”

“Absolutely.”

Four-man bob or two-man bob?”

“A two-man bob,” I replied, not wishing to share the glory with three Swiss.

One of the chortlers clamped a helmet on my head, installed me on the bob behind the pilot, and gave our bobsled a good shove with his foot.

In less time than it takes to say Arnold Winkelried or even William Tell, I realized I had made a bad mistake.

At the very start my left hand was wrenched free and I held on desperately with the other hand. For a fleeting second I contemplated letting go with my right hand and sliding gently off the sled. But the speedy, twisting ride discouraged me. I abandoned the idea when we slammed off the icy walls, sometimes apparently flying upside down. Sky and ice were everywhere.

As the bobsled accelerated, the driver kept hollering at me. I thought this was a poor moment for conversation and just did my best to hold on. He went on shouting words into the wind. At long last, which is to say barely over a minute later, the sled slid to a stop at the finish line.

I jumped up, my legs buckled and I crumpled back onto the bobsled.

Green with fear and anger, the pilot leapt up and cried: “Are you mad? Didn’t you hear me tell you to brake? You nearly killed us both!”

“Brake? I didn’t know I was supposed to brake, and anyway you never told me where the brake was.”

“We thought you knew. Nobody in his right mind goes down an Olympic bobsled run without braking.”

Just then the loudspeaker announced that the team of Bumpernagel and Ress had broken the season’s Olympic piste record in one minute and a few seconds.

I was elated; the pilot was not consoled.

Three years later in February I returned to St Moritz looking for a story. During a conversation with the resort’s tourism director the subject turned to bobsleds.

“Wouldn’t you like to go down our Olympic bobsled piste? It’s really exciting. Anyway, you wouldn’t be the first American journalist to do it. A few years ago an American reporter went down the run. He refused to brake and he set a course record that lasted throughout the whole season. What an incredibly courageous fellow he was!”

“Courageous?” I said, “He was a damned fool. It was me!”

Not surprisingly, Paul became one of the most successful reporters for Time magazine, scoring story after story in the feature sections while others in more ‘newsy’ regions struggled to get the attention of their news editors.

After the Riviera Paul moved to Switzerland to work for the United Nations Environment Programme in Geneva. He developed a formidable reputation for finding stories that journalists wanted to publish by concentrating on information rather than PR.

At one conference he persuaded the International Herald Tribune that a story from a small U.N. organization was worth its front page. The organization boss was terrified that he would be in trouble with the big cheese holding the conference for stealing his thunder and banned Paul from talking to any more journalists. The big cheese could hardly believe it. “How did you do that?” his assistant asked Paul. “We’ve been trying to get the paper interested in us for years.” Now the conference was on every journalist’s radar, and Paul’s boss spent the rest of the meeting basking in interviews.

It’s a skill he has practised throughout Europe and many other parts of the world for the likes of UNICEF, WHO and even the International Trade Centre.

Paul insists he settled in Switzerland because “you can go just about anywhere with your dog”. Paris might seem more likely to win the title of dog-friendliest city, but Paul disagrees: “I have lived in Paris with two boxers and Geneva with three bearded collies. I can assure Parisians, and American dog-lovers, that Geneva is the doggier of the two.” In fact, he could even take his dog Sophie to the cinema in Geneva.

Paul’s one-time colleague, the historian Steven Englund, says: “What makes a good newspaperman? Very simple: it requires clear prose, felicitous metaphors (but not too damned many), complete integrity, and a passionate commitment to the truth. No wonder there are so few good ones. Paul Ress is a good newspaperman. [But] if Paul does anything better than reporting, it is friendship.”

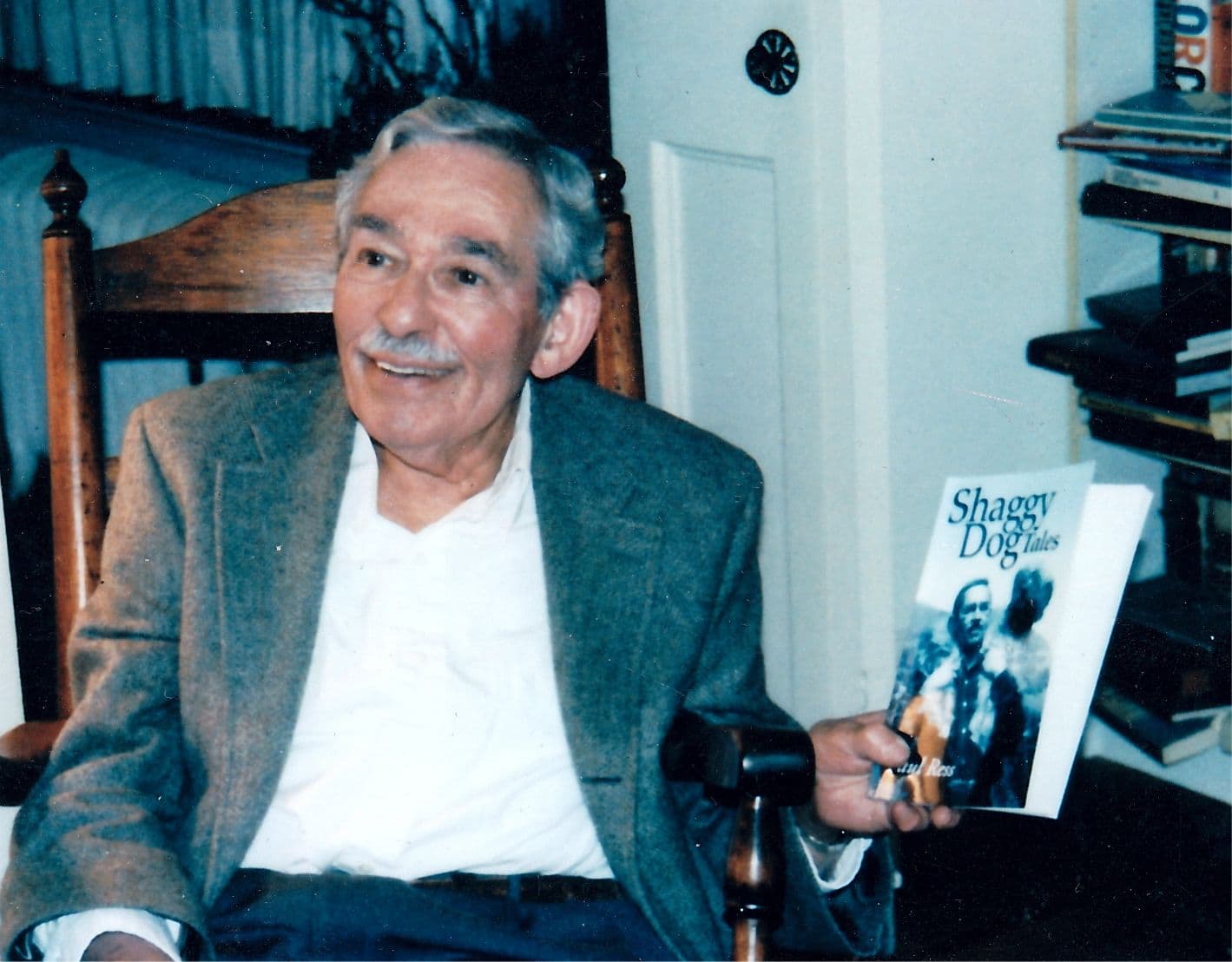

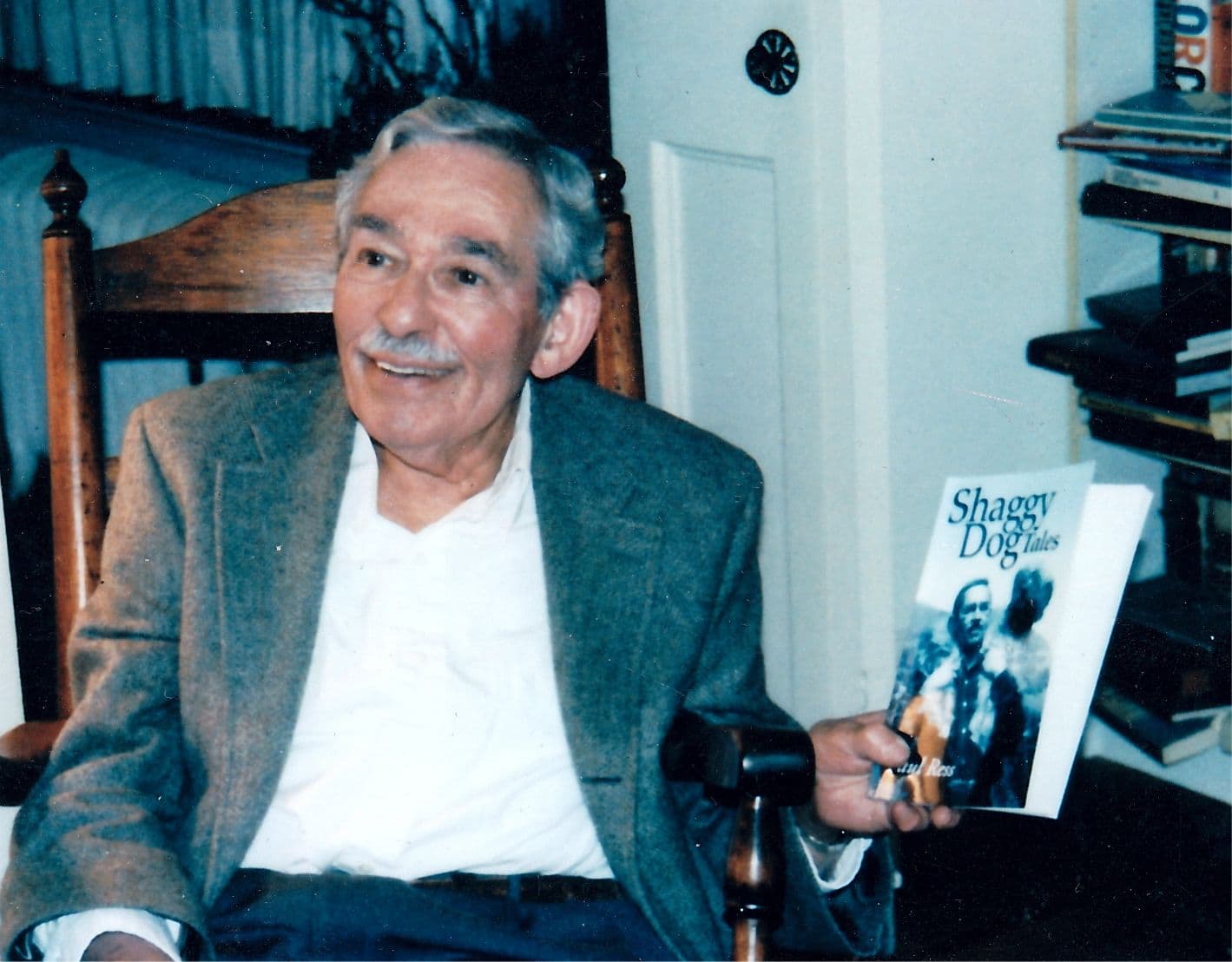

Paul was persuaded by his friends to gather some of his stories and notorious puns into a short book entitled Shaggy Dog Tales: 58 ½ Years of Reportage, published by Xlibris at $9.99 for the e-book version, $20.99 as paperback, and $30.99 for the hardback edition. The renowned British biographer Caroline Moorehead, who also worked with Paul, describes his book as a “collection of charming and funny pieces, many about a lost and vanishing world”. One bonus in the book, which makes it worth the price for any information officer, is Paul’s thoughts on how to be successful with journalists. His message is very popular with hardened reporters and suspicious correspondents. Typically, for this uncontrollable punster, Paul’s guide is entitled Flackery will get you nowhere.