Understanding PTSD: The Hidden Struggles of Translators

This article delves into the often-overlooked struggles of translators dealing with PTSD in conflict zones, highlighting the urgent need for mental health support.

This article delves into the often-overlooked struggles of translators dealing with PTSD in conflict zones, highlighting the urgent need for mental health support.

This article also has appeared in the Oct/Nov 2017 print and e-edition of Global Geneva magazine.

Most foreign correspondents covering conflicts and humanitarian crises, including those who somewhat presumptuously dub themselves “war reporters”, like to imagine that we are not particularly affected by what we see. We’re a tough lot and we’re certainly not going to go soft by admitting that we have been traumatized by what we have witnessed in Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Rwanda, Congo, Bosnia, Iraq, Somalia, Syria…

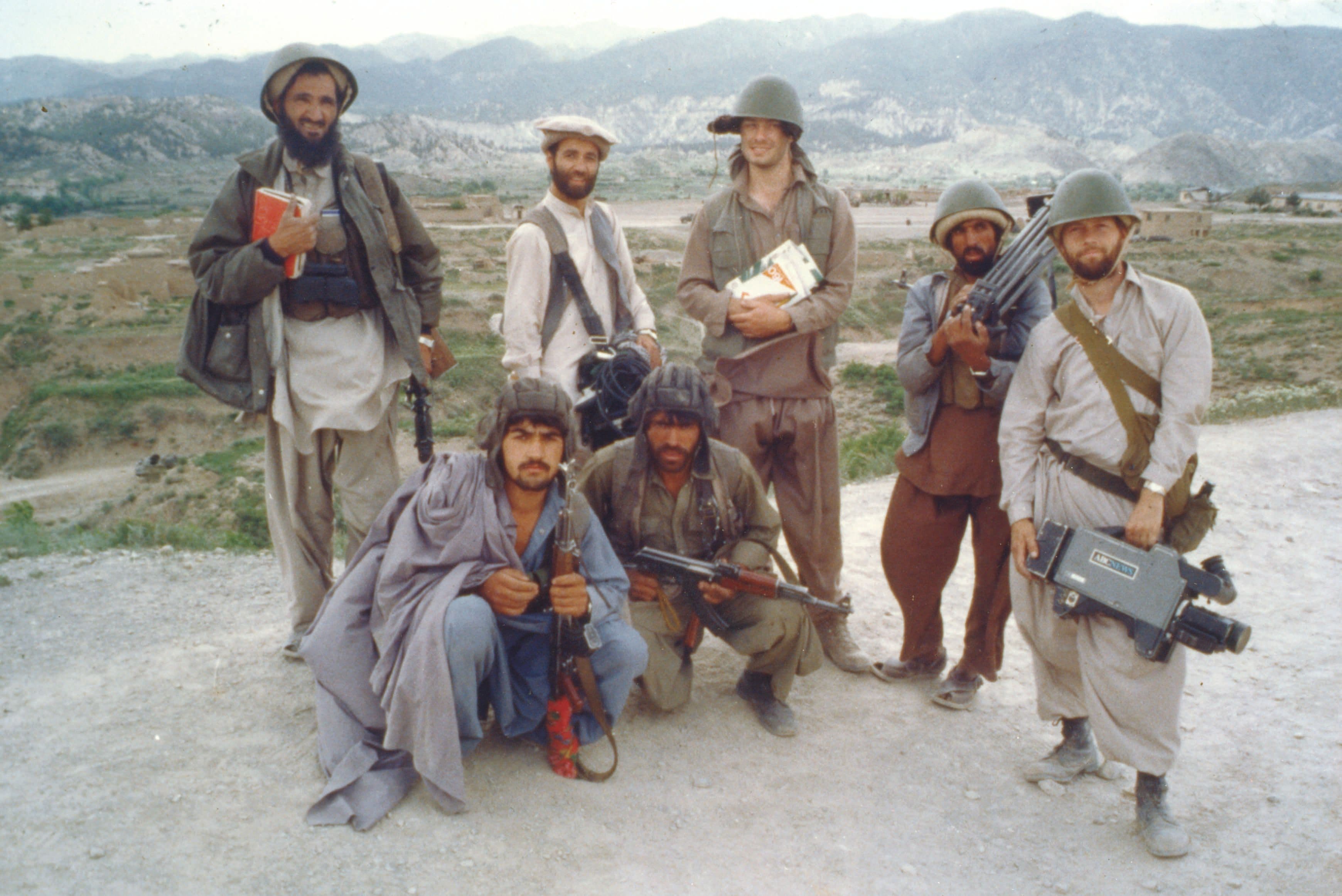

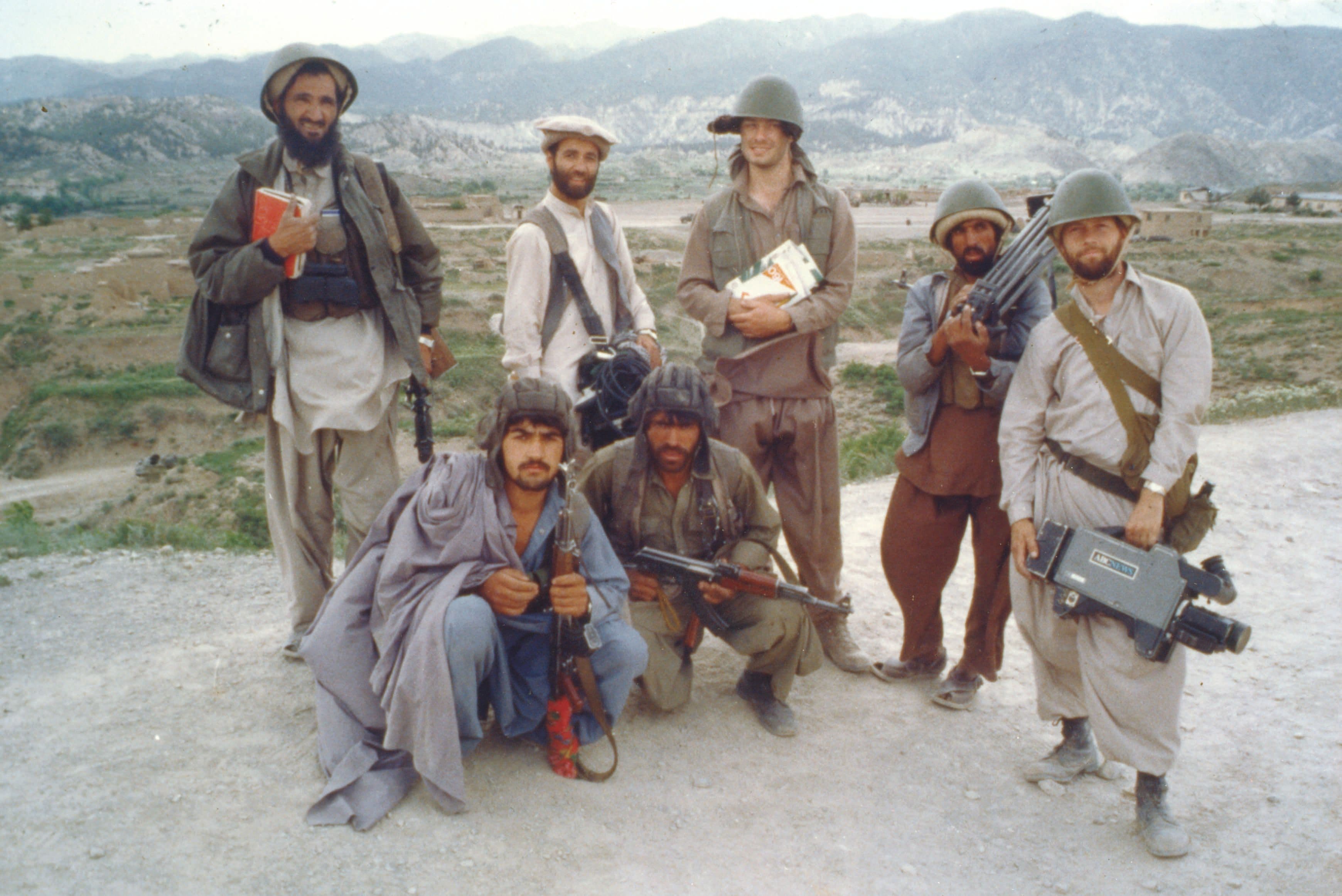

Or at least, that’s what we like to tell ourselves. As Terence White, a New Zealand reporter, famously announced in an Afghan guerrilla hideaway during the Soviet-directed war: “You’ve got to learn to take steel.” The fact that he ended up severely wounded by shrapnel half a decade later in Kabul was probably not what he had in mind.

Much of our machismo is false bravado, a coping mechanism. Print reporters write “I was there” stories from the frontline but don’t actually hang around longer than necessary to put together their pieces. They can always talk to people later about what has happened and a good writer can turn disparate facts from the field into something poignant. Nevertheless, our day-to-day experiences are often horrendous even if we don’t recognize it at the time: a near escape from an IED (improvised explosive device) or the sudden discovery that you have wandered into a minefield - when someone just behind you veers slightly to the left and in the shocking explosion one moment later loses a limb.

TV reporters and producers in the era of instant news are required by their organizations to ensure that to illustrate their ‘standuppers’ they have dramatic footage – often shot by freelance cameramen who are the real ones risking their lives – or, increasingly today, social media videos, which may or may not be the real thing. Some of these journalists are incredibly brave. Others struggle under the time restrictions imposed by New York or London to feed “the bird” – the satellite – and ratings-greedy bosses who forget that wars do not respect time-tables or people. One ABC news producer during the 1990s Bosnian war was under such pressure that he and his colleagues decided to venture across the airport tarmac in Sarajevo in an unprotected vehicle despite warnings by colleagues. He was killed by a sniper’s bullet. His death was bad enough, but so was the impact on all those forced to watch. These are images one does not forget.

It’s hardest for the photographers, however. They actually have to be there to record what is happening if they wish to sell their pictures. Their coping mechanism is to hide behind their lenses. It makes them feel protected and beyond reach. It’s a strange form of detachment and it regularly gets photojournalists killed.

So most of us persist as foreign correspondents, regardless of what we endure. Then we look back at our notes and admit we were complete idiots for having taken such risks. But we have our jobs to do, we tell ourselves. So we parachute in and out of war zones, meeting up at night in bars or dilapidated hotels to boast about our experiences. Eventually, we head back to Paris, Geneva or Berlin before moving on to the next story. And this can continue for years.

But no matter how courageous foreign correspondents may be, others around them are in even greater danger. Unlike ordinary people struggling to survive in their war-shattered towns and villages, or the UN and NGO aid workers who have opted to remain on the ground providing medical and other forms of relief for weeks or months on end, we journalists can always pull out.

Of course, a lot of our tough veneer is utter rubbish. Many of us are deeply affected, but we don’t wish to admit it. We talk about the ‘action’, the adrenalin surges and the excitement; we rarely talk about how it affects us. That’s far too personal.

One experience in particular came back to me when I was reading Ed Gorman’s book, Death of a Translator..

I was in Somalia in 1991 prior to the US intervention. There were no more than four or five journalists around. For the Western media at that time, the First Gulf War was the ‘real’ war because it involved American and other allied troops. No one really cared about Somalia’s atrocious civil war, though 300-400 human beings were being injured or killed every day.

I had just left Afghanistan and Sri Lanka and found myself driving around Mogadishu in a borrowed UNICEF vehicle with Peter Jouvenal, a highly experienced British cameraman and producer. He was not someone you would describe as an openly ‘sensitive’ human being, but then he had been shipped off to English boarding school at the age of six. You learn to be tough there, or at least to hide any weakness, as a matter of psychological survival. At the same time, almost secretively, Peter was incredibly kind. But he made damn sure that no one knew it.

We ended up driving around the capital and the outlying sand dunes, literally dodging bullets and mortars, and avoiding drugged out factional fighters (we were kidnapped at gunpoint twice in one day). Then, several hundred metres ahead, an anti-aircraft shell (the factions used such weapons to fire indiscriminately into rival enclaves across the city) smashed into a local market, killing 40 people and wounding scores more. We immediately loaded several of the injured into our pristine white UN vehicle. We drove to a nearby medical station run by Somali medics, including at least one completely exhausted doctor who had not slept for two and a half days.

Outside there were perhaps 20 dead – men, women and children. Their torn bodies were neatly lined up in front of the clinic. Nearby, in the sand a group of seven or eight-year-old boys were playing marbles with polished stones. They paid no attention to the corpses. The bodies had already become part of the scenery.

Inside the building the Somali doctor, who had been trained in Germany, conducted triage as the victims were carried in. No, no, yes, no, no, he would say to his aide, an equally exhausted Somali woman. This one won’t make it, take him outside (to die). Nor this one. Here, this one, send him to op.

We filmed dutifully, but we never used the footage. It was too abhorrent. A German journalist was picking his way among the bodies, his feet trudging two inches deep in blood. At one point he fainted, stumbling backwards with his camera. Peter and I laughed and helped him outside. Silly bugger. Why cover this war if you can’t take it? Of course, all we were doing was covering up our own weakness. Black humour tends to help ward off the horrors by stashing them deep into the recesses of our minds. It was a way of putting up a psychological barrier that no one should ever be allowed to penetrate.

Strangely enough, it was this particular scene that I recalled when reading Death of a Translator. It struck me that I had repeatedly dreamt or otherwise revisited this brutal day in my mind over the years. It was a painful experience but then, I kept telling myself, it was normal, just part of a despicable war and there was nothing you could do about it anyway.

Gorman, who is a friend but who never really told me what had happened, writes about many incidents including the death of an Afghan fighter, his translator, who is commemorated in the book’s title. Abdullah-Jan was killed in a Soviet attack. Ed had known him well but all that he could recall was his friend’s body being carried, almost as if he was still alive, down the mountain on the back of another man. Gorman also shivered at the thought that he had casually smoked Abdullah’s remaining cigarettes while waiting for his burial. Is it okay to take a dead man’s smokes?

There were other memories which haunted him for years: non-stop Soviet helicopter attacks, the threat of being betrayed by informers, or having to hide in a tomb-like cavity under the floorboards of a safe-house in Kabul for fear of being discovered by KHAD, Afghanistan’s equivalent of the KGB, as they searched for resistance collaborators. Being captured even as a reporter for The Times could have meant summary execution as a spy or at least prison with a very public propaganda trial.

For years, Gorman thought that he was suffering from the effects of malaria, dysentery or one of the other Third World ailments with the familiar medical names that tend to affect travellers. He went into depression, drank, took drugs and sought solitude deep in the Irish countryside well away from other human beings. He also abandoned journalism. He eventually returned to reporting, in conflict zones such as Northern Ireland and Bosnia. But soon he recognized that he could no longer continue as before, particularly as a foreign correspondent. He did make a couple of return trips to Afghanistan, but then found it impossible to even contemplate covering that (still) ongoing war, today in its 39th year. Or any other war for that matter.

It took numerous medical tests and consultations for Gorman to understand that what he was enduring was in fact Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. PTSD affects aid workers, soldiers, firefighters, air or car crash victims and many others who have experienced shocking, terrifying or dangerous events. As Gorman writes, one day he froze at his desk. He called his editor on the phone for help and got the reply that this was not the time to ask for a raise. In the end, his editors grasped that something was seriously wrong.

Gorman’s doctors finally pinpointed the true nature of his illness. In America, where he had taken a break to ‘paint’ houses rather than work as a journalist, he was diagnosed with “Acute Nervous Exhaustion”. Later, back in London at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, he was told to “slow down and box clever”. Gorman writes: “For the first time, I had a clear diagnosis that made sense, even if I knew little about post-traumatic stress disorder and had never considered that it might be the key to my condition.”

Once Gorman was diagnosed with PTSD, the doctors finally gave him the care he needed. This included a spell at the same institution in England where kidnap victims from Beirut and other Middle East countries had been treated. At first, Gorman was embarrassed about entering a “mental hospital” which also turned out to be Europe’s oldest privately run psychiatric clinic. He thought of leaping out of the car and running back. But the process of “unburdening” himself was critical, even though Gorman feared exposing his own private thoughts to others. For some, the process can take weeks or months; for others years. For Gorman, it took six months for him to sort out his demons allowing a positive change to emerge.

As Gorman writes, he was finally able to return to a normal life, but not to covering war zones. Instead, he became The Times’ yachting correspondent – he had a lifelong passion for boats – and eventually became deputy head of news. A journalist friend of his, he writes, was not so lucky. This man committed suicide with the help of drink and drugs at the age of 50.

PTSD is prevalent, too, among relief workers. Many international aid agencies, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross and Médecins sans Frontières, now provide counselling and therapy for their personnel, particularly those operating in war zones, on their return to ‘civilization’. This is a crucial process. People need to talk about their experiences and to get it out of their system. But it was not always so.

During the early 1990s in Liberia with MSF, I was filming with French film-maker and writer Christophe de Ponfilly. There we realized that the entire medical team on the ground were traumatized. They had been in the war too long and had witnessed too many terrible things, dealing with countless victims who had endured incessant rape, brutalization and the execution of their friends and loved ones. The team leader was completely dysfunctional. We ended up telephoning Paris beseeching HQ to pull the team out. It took a while but it was finally done. Yet, it still took years for MSF to introduce regular debriefings of personnel on their return to Europe. News organizations, thankfully, are today more aware of the problems than then.

Sadly, my friend Christophe committed suicide. He had his own reasons for depression, but part of his mental disarray, I am convinced, resulted from PTSD based on what he had experienced in places like Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, El Salvador, Mozambique and other war zones around the world.

Death of a Translator is brutally honest. It is also written in a straightforward readable style. It was, Gorman later told me, a book that had to be written. As he saw it, putting it all down on paper was also part of his recovery process. The book is appealing, easy-going, even somewhat romantic. He acknowledges the importance of finally falling in love with the right woman, Jeanna, who knew how to deal with both his character and troubles.

Of course, writing this review, I wonder whether I myself have suffered, or still suffer, from a form of PTSD. Maybe. Like any ‘tough’ foreign correspondent I am adept at hiding what I really feel. I am not particularly proud of the fact that I go to extreme lengths to cover up my emotions, something which often does not bode well in a marriage. I know this is a weakness. On finishing Gorman’s book, I found myself silently promising to explore my own situation. Looking back, my own long treks in Afghanistan probably served as a psychological balm to what I had witnessed. What else do you do when you have to walk 16 hours a day? You think. You ponder. You undergo a spiritual cleansing.

This became harder in other wars, where there was no trekking or the possibility of ‘cleansing’ walks. How I miss those Afghan treks. Walks in the peaceful Swiss Alps are simply not comparable, however refreshing. But it is still hard for me to admit that something might be wrong. Like old soldiers, we simply don’t talk about it. That is why I am grateful to Ed Gorman’s book. It might help more of us face up to the truth.

Edward Girardet is editor of Global Geneva. He has reported wars and humanitarian crises for more than 30 years.

Death of a Translator. By Ed Gorman. Published June, 2017 by Arcadia Books.