Discovering Ghazni: A Treasure of Afghanistan's Heritage

Unveil the rich history of Ghazni, Afghanistan, and its remarkable architectural heritage. Learn about the city's significance, cultural gems, and travel insights for the adventurous soul.

Unveil the rich history of Ghazni, Afghanistan, and its remarkable architectural heritage. Learn about the city's significance, cultural gems, and travel insights for the adventurous soul.

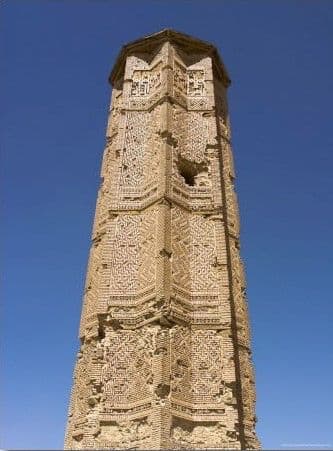

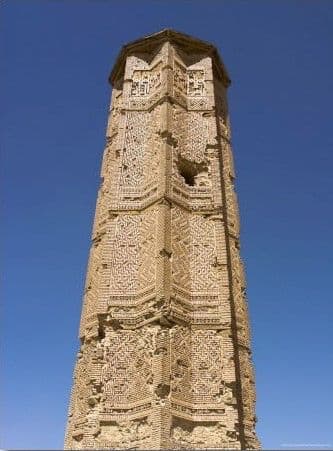

FIFTEEN YEARS AGO, IN SEPTEMBER 2003, I journeyed to Ghazni, whose name means “jewel,” situated on Highway 1 south of Kabul. A trading and transit hub for central-eastern Afghanistan, it is now a city of 270,000 people sitting on a plateau 2200m above sea level. Its towering citadel and ornate, honey-coloured twin minarets dating back to the 12th century bear witness to the days when it was the capital of a vast empire and a major cultural centre of medieval Islam. Places like Ghazni remind us how relative such terms as “medieval” and “renaissance” are.

It had colleges, libraries, schools of scholars and poets, palaces of marble and statues of bronze at a time when the Italian survivors of the Roman period were still huddling for safety amidst the ruins of their fallen empire. Firdausi, whose epic poem the Shah-nameh soars as an Eastern Aeneid, and Al Biruni, the empirical polymath whose mathematical, astronomical, mineralogical, and anthropological studies made him the Leonardo da Vinci of his age, strolled through its splendid gardens where “wine flowed like water,” as the historian Baihaqi relates.

“The environs of the present Ghazni would prove a perfect archaeological mine to those interested in and acquainted with Muslim history and architecture,” wrote the pioneering British scholar Major Henry George Raverty. And indeed they have – in happier times.

Yet, as Rome and Ghazni show, history has its tragic reversals, and it was another type of mine entirely that drew me there on a late summer day two years after the Twin Towers fell in 2001, at a moment when the world could still hope for another Afghan Renaissance.

My trip to Ghazni was as a guest of the Mine Detection Dog Center in Kabul. It uses highly-trained German shepherds to discover sophisticated land mines that would otherwise escape metal detectors. I was writing a feature on making dangerous places wholesome again. As a journalist who always tries to gain a full cultural and historical sense of any country I cover, I made sure to take along Nancy Hatch Dupree’s matchless 1977 guidebook, An Historical Guide to Afghanistan, which has a particularly rich chapter on this city, “the all-important key to the possession of Kabul,” as she put it.

As we drove southwest from the capital – an hour and a half jaunt according to the book, but one that took four times as long, due to the fact that the war-ravaged main highway was just beginning to be reconstructed – I asked my hosts how Ghazni’s great monuments had fared over the last quarter century of war.

“We had a Buddha too,” sighed Hakim, the local de-mining chief and a Ghazni native. “It reclined instead of standing, and even had pillows to rest its head on – very special. It was 18 metres long. The Taliban blew it up at the same time they destroyed the twin Buddhas in Bamiyan, right before September 11th. The citadel is a military fortress, and so sustained much damage, but it is big, and can take it. The mausoleum of Sultan Mahmud is untouched, but that of his father Sabuktagin up on the hill was devastated. The twin minarets still stand, though the one built by Bharam Shah took a direct mortar hit near the top, and has a big black hole there, like an empty eye socket.”

I winced at the thought of all that intricately-worked terracotta flying through the bright, clear mountain air, spewing fragments of its perfect geometric patterns over the ground.

Standing atop the highest point of the citadel, one can behold a lush panorama of many shades of green articulating the river valley and surrounding mountains. Yet this picture of natural fertility is deceptive. In recent years, the region has been hit by persistent drought, among other plagues, and the trees hide many arid, pale brown, and even grey fields.

One of these just north of the city was our first stop: a wheat field that had been turned into a minefield by the mujahideen during the Soviet invasion. It was sown with high-grade plastic mines supplied by the Italian government as one of its contributions to the international support for the Afghan resistance. It was then forgotten, as Afghanistan’s agricultural potential was disregarded in the Pakistani aggression that put the Taliban in power and the world blinded itself to the consequences.

A band of Kuchi nomads had recently lost several camels and sustained serious injuries while traversing the field. Now the mine detectors were trying to fix it.

I saw a well-delineated rectangle, marked at precise intervals by small red and white flags to indicate which areas had yet to be cleared and those which had already been de-mined. They stood out against the dun ground like splashes of blood and panels of marble. In the crimson area four dogs and their handlers worked methodically, the canines doing a graceful backflip after they smelled the explosives, to be rewarded with treats. The team would then withdraw as diggers came forward to remove the mine from the grey field. “It’s been a minefield for twenty years,” said Hakim, “but next spring they will sow wheat here again, God willing, though they will have to irrigate it.”

After several days of observing the demining operations, I made time for some sightseeing, The prospect was all the more exhilarating since I was aware that the Italians had once been responsible for excavations of a very different kind in Ghazni: the recovering of a rich cultural history. As Dupree relates, in 1956 the Italian Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan had taken up Major Raverty’s challenge, and did brilliant work until the communist coup of 1978 in Afghanistan. I was determined to see what remained of the Italians’ discoveries.

Following a sumptuous lunch of seekh kebab, a lamb dish for which the city is famous, we set out for Ghazni Citadel. The arduous ascent and descent took several hours. At the end the view alone was worth it. Then we went on to the mausoleum of Sultan Mahmud, the greatest of the Ghaznavid emperors, whose conquests and patronage made possible the life and legend of the city. Unlike most Islamic art, the Ghaznavid style was iconic, heavily influenced by Persia and India. The tree-shaded lane leading to the tomb was graced by marble lions and rams, from whose mouths gushed refreshing streams of water.

At the entrance, a small boy dressed in spotless white offered us some naan roghani bread. When I politely declined, the boy insisted:

“Please sir, it is our tradition. All who visit the shah shall receive. It was the way in his time, and it is the way now.” I could not deny those sincere eyes or the wholesome logic behind his plea.

I was glad I conceded. It turned out to be the most richly delicious bread I have ever tasted in Asia.

By the time we reached the twin minarets, known as the “Towers of Victory” as monuments to Afghanistan’s greatest empire, the sun had begun to set. It is a wonderful time to see them. They seem to gather all of the waning light unto themselves, soaring like golden shafts against a deepening blue sky. Yet, for all their grandeur, I could not dwell on them. I was also here to find a hidden splendour which I knew to lie nearby.

Perhaps the Italians’ greatest accomplishment at Ghazni was the excavation of the palace of Sultan Mas’ud III, which was said to be located somewhere between his minaret and the main road. It was quite elaborate, with a throne room, government offices, royal apartments, gardens, and even its own mosque and bazaar, all arranged around a courtyard of delicately carved marble.

However, as I scanned the grey plain of gravel and brush from which the minarets rise, no hint of it was visible to the naked eye. So I had no alternative but to head towards the point on the map in the guidebook that shows its relative position, and then to tramp around.

This my hosts were very reluctant to do. They were, after all, demining experts who had no definite information about the safety of this out-of-the-way spot. Still, they yielded to my enthusiasm, and I was soon bounding about the jagged ground, with Hakim and his men following cautiously. As I had hoped, a fragment of marble revealed the place leading to human-made mounds beneath the brush.

I yelled to my companions, who scrambled over to see, then received an improvised lecture on the palace from me.

After a pregnant silence, Hakim spoke, visibly moved. “We have lived all our lives in Ghazni, but we never knew this was here, or had even heard of it. Interesting, the way the name ‘Mas’ud’ keeps recurring in Afghan history.” he said, referring to the legendary mujahed leader Ahmed Shah Massoud from the Panjshir. “We thank you for giving back to us a part of our tradition that was lost.”

As we drove back through the city to the demining compound past groups of ragged and dirty children, I wondered whether they were going to be educated about the totality of their heritage and given the chance to emulate the achievements that these monuments embody, as the world had promised them. All their lives they had known only blood. Would they be allowed to strive after marble?

Over half a century ago the American scholar Arnold Fletcher wrote that Afghans “are a people of dynamic energy, quick to learn, fiercely patriotic and determined to prove their worth in the modern world”. Forty years of continuous war have not altered this reality, and the talent and spirit are still there.

Yet a decade and a half of blindness on the part of the United States and its Western allies has produced a negative answer to this question. By refusing to recognize the tragic truth that it had defeated Soviet political extremism on terms set by Pakistani religious extremism, then walked away from its responsibilities and suffered the consequences on September 11, 2001, America for the second time threw away its victory in Afghanistan.

Yes, those years saw the Americans launch many rebuilding and reconstruction projects in Ghazni, most notably the Lincoln Learning Center that strives to reach out to 4,000 citizens every month. However, without security, what has taken years to build can be destroyed in an instant.

Earlier this past summer (2018), an estimated 1000 Pakistani-backed Talib militants devastated Ghazni over six days of savage fighting, burning bazaars and law courts and killing hundreds in yet another climax in the collapsing security situation around the country.

At the same time, a suicide bomber walked into a high school classroom in Kabul filled with impoverished students from Ghazni taking a college preparatory course. He killed at least 48. The classroom’s blood-spewed whiteboards were crammed with the algebraic equations upon which Al Biruni had laboured so diligently in the splendid gardens of their hometown a thousand years before.

VANNI CAPPELLI, an American freelance journalist, is the president of the Afghanistan Foreign Press Association.

The editors urge high school students in Switzerland to submit personal articles, essays or other media initiatives for Global Geneva’s June, 2019 media awards focusing on ‘international Geneva’ themes ranging from humanitarian response and culture to human rights, climate change and world trade, or any of the Sustainable Development Goals as part of this year’s Young Journalists’ and Writers’ Programme. And to participate in Global Geneva’s journalism and writing workshop 27 March, 2019, to learn about the crucial need for credible reporting in the public interest but also how to communicate effectively about issues in which they believe. See www.global-geneva.com for more details.

Support Global Geneva. If you would like to help bring quality journalism and public awareness of the need for credible, fact-based information to young people, please donate or otherwise support Global Geneva initiatives. We cannot do it without your help.

Related articles in Global Geneva on the destruction of cultural heritage in time of war.

Erasing history: ISIS, Balkans, US Civil War statues, and Saddam Hussein.

Afghanistan: Struggling to preserve a country’s heritage

Afghanistan’s Unwinnable War. A journalist’s reflection on 40 years of conflict.