Navigating Life as a Trailing Spouse in Geneva

Uncover the unique journey of trailing spouses in Geneva—balancing personal identity, cultural integration, and navigating international relocations. Join a community of global citizens!

Uncover the unique journey of trailing spouses in Geneva—balancing personal identity, cultural integration, and navigating international relocations. Join a community of global citizens!

My identity boils down to an airplane landing card. It’s that dreadfully loaded question, that 10-letter word that used to have me turn to my husband and ask: “What should I say I am?” It used to be easy. Profession? For a while it was “student”. Then, for more than 25 years, much of it spent in conflict zones, I wrote “journalist.” I’ve been seven years off that wagon now. I used to cringe, was often tempted to lie. There was that occasional slight tightening of the chest, that fleeting moment of angst that I wasn’t anybody. Or at least anybody that I deemed worthwhile meeting. I am now vague, undefinable, unexplainable. I am a “spouse”.

Or more precisely, these days, I am commonly referred to as a “trailing spouse”. I married in my 40s. My 11-year-old son, Lucas, the product of the union, jokes I’m ancient. When Lucas wasn’t quite four, my husband, John, was posted to Kenya for the World Bank. It was a return for both of us to a country we had worked and lived in years before we met. There was only a small glitch. It was difficult to get a work permit, especially as a journalist. Even harder if you are a freelancer who, having spent years covering civil wars and a genocide in that region, had no desire to go back to conflict reporting. As friends called to congratulate us and to ask when they could visit, one British colleague emailed to ask me if, as a World Bank spouse, I was looking forward to hosting weekly afternoon tea parties for the Nairobi ex-patriots.

It was, I have to admit, quite a well-aimed jab at my self-centered insecurities. I was jobless, heading into a spousal world where I had never dared to venture. And besides, I don’t do tea. I don’t drink it. I don’t serve it. But in the yin and yang of adapting to spousal life, I did savour this colleague’s gumption a few months later when I received an email asking me if I’d arrange an interview with my husband. Many others since have asked me to facilitate access to him. But John, a trailing spouse himself in his first marriage, brushed off my indignation: “Just tell them I have my own email address and you are not my secretary.”

Four years in Kenya. Almost three years in Nepal. Now almost a year into a four-year assignment in Turkey. It’s a process. Like learning several languages at once. There are plateaus, there are steep climbs and the occasional tear-stained crash. The trip I have taken as a “trailing spouse” is deeply personal and has as much to do with addressing my roller-coasting sense of identity as it does learning how to pay an electricity bill in a foreign country.

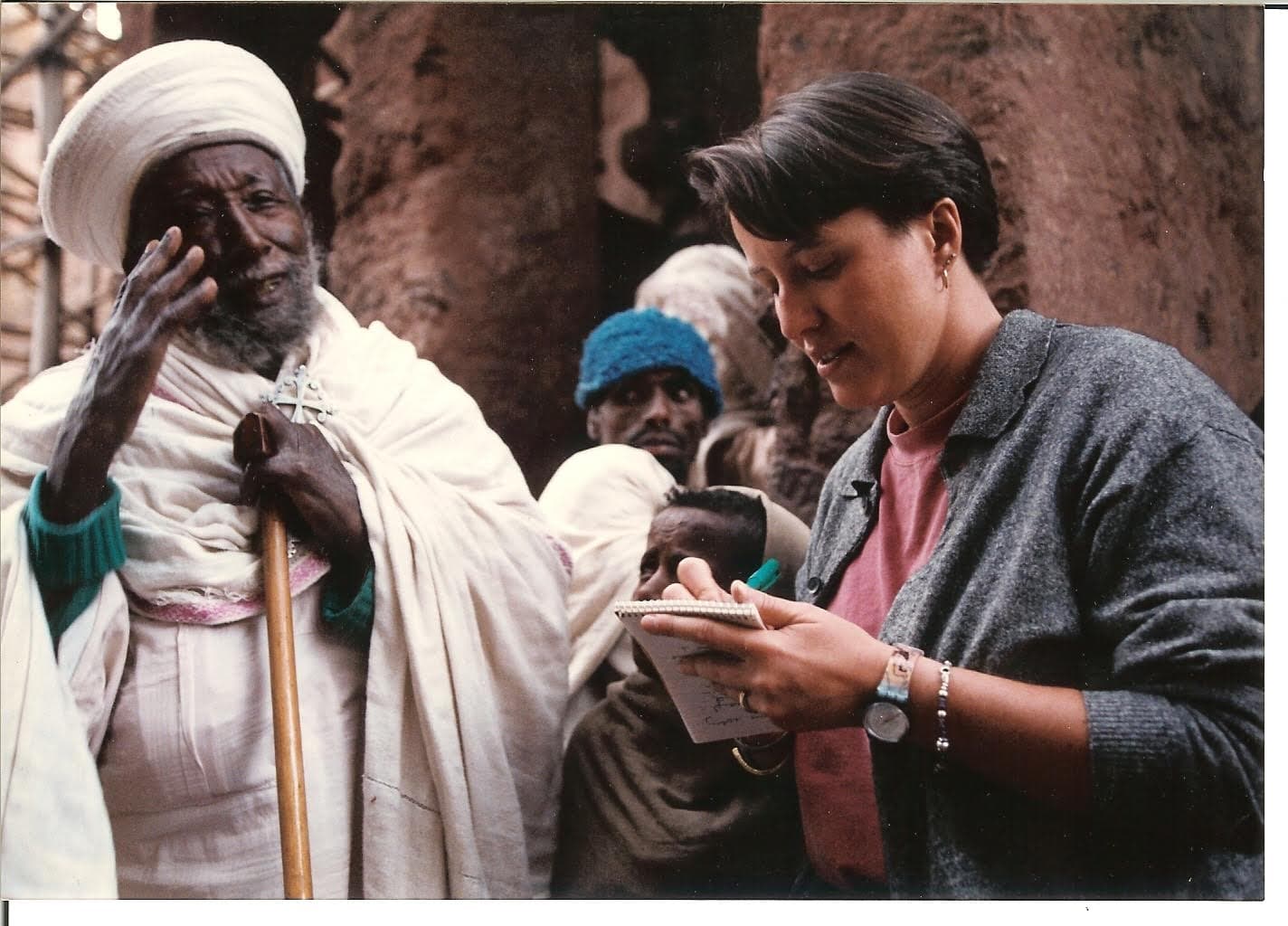

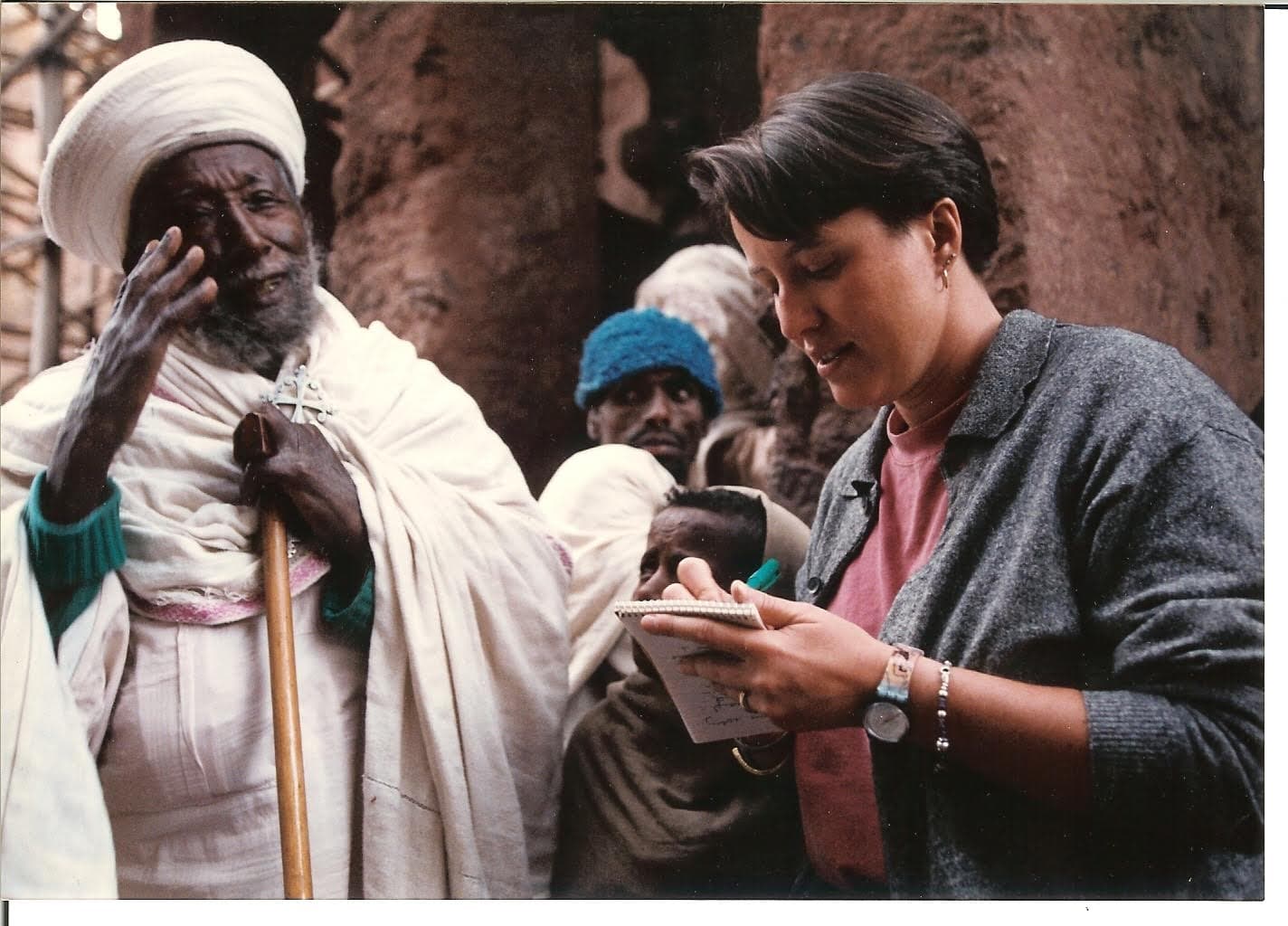

I’ve missed being in the thick of breaking news. Since I crossed into Afghanistan in my mid-20s with the Mujahidin (holy warriors), reporting has been my unrelenting beast inside. Many World Bank couples work in the same field and they lead a long-distance commuting lifestyle on airplanes. I wanted to live with my new husband. I wanted to explore. I wanted adventures I would not find in suburban Washington D.C. His job offered all these possibilities. But being rather undiplomatic, I had no idea how to be the unemployed wife of a diplomat.

In hindsight, Kenya was an emotionally smooth country. It was easy to be the old me. I had many friends there from my previous posting with The New York Times. People knew me by my byline. They knew me by my last name, not my husband’s, and sometimes they referred to him as “Mr. Lorch”. It pleased my ego. I hopped between UN and USAID consultancies. John gave me a dog, a very big dog. Biko may be a bureaucratic nightmare to move between countries, and John subsequently learned that he is highly allergic to him, but Biko brightens the darkest days. He has been and continues to be my great emotional leveler.

We arrived in Nepal in 2013, but almost immediately – due to complex World Bank reorganizations – John was moved to Bangladesh. For the first time in decades of traveling, I went through what I assume is culture shock. I was jobless, lonely, alone, unhappy, alienated.I felt pathetically insignificant.

My days were spent on lines to buy diesel and cooking gas and to track down which store might have broccoli or asparagus. It gradually occurred to me that everything everyday had the heartbeat of a story starting with the logistics of Nepali survival. I bought milk from a local cow I met on one of my Biko walks. With little reliable electricity, I made yogurt wrapped in blankets. I hoarded 120 litres of diesel for our car and generator in my garage (this was pure gold during a five-month Indian fuel blockade). I planted beans, lettuce and basil and froze pounds of pesto for winter spaghetti dinners. In this highly seismic region I obsessed about earthquake preparedness, storing water and food and clothes in our yard. I made friends. I learned to love running. I had fun.

I started to write again. About my life. About life in Nepal. NPR occasionally assigned a story. I tried to avoid political topics but I doubt anyone in the government bothered to read the American press. My representational role as the wife of the head of mission was limited to the occasional party where the Scotch flowed fast and freely. Then the 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit.

Few international news organizations had anyone nearby so for a short while I was flooded with requests. There is nothing quite like the heart-thumping, almost giddy feeling of being in the middle of major breaking news. But here I was living it, not just reporting it. This was my home and I interpreted what I saw in a personal way I had never reported before.

Unwilling to leave Lucas at home because of frequent aftershocks, I brought him with me on reporting trips to mass cremations and collapsed towns. Only later, once settled in Turkey, did I realize that being a trailing spouse for two years in Nepal had given me a unique gift. I belonged. With John often out of town, I had an extended family at the World Bank office in Kathmandu. John’s assistant, Kiran, virtually adopted me, including me in office events, bringing me sacks of apples and potatoes from his village in the far west. He was the first one to check in on me post-quake, even though part of his own house had been damaged. I felt that someone always had my back. I hadn’t felt that since my reporting days in Mogadishu, Iraq and Pakistan.

Somehow, I’d managed for years to avoid most of the expected diplomatic socializing. In Turkey, I don’t know what was more nerve wracking for me: wearing dresses and panty hose for the first time in decades (I still ban high heels in my closet) or attending my first meeting of the ‘Spouses of Heads of Mission’ (SHOM). I’ve recovered. In Turkey, where scores of journalists have recently been arrested and newspapers closed, I have no problem defining myself as just a spouse, especially on the landing card. Forget about the work permit.

Early on, I had lunch with the Turkish President’s wife … with a hundred other SHOM members and an army of choreographed Mozart-dressed waiters. I felt like an imposter, until I met some down-to-earth practical and funny women. They, too, were trailing spouses. My life in Turkey is far from glitzy. I’ve spent long days with a group of Iraqi refugee women. As I struggle hopelessly at times with Turkish, I practice my miserable grammar exploring the worlds of farmers, neighborhood police, shop owners, hairdressers, and of course dog-owners that I meet walking Biko. The language barrier is definitely isolating but without my own set of work colleagues, Biko and a few Turkish and ex-pat friends have proven indefatigable door-openers.

I no longer fight who I am – even as that changes from day to day. I still have my demons. But I haven’t been co-opted. It’s not a masquerade. To quote Norah Ephron: “Everything is copy.”