Experience Funky Jazz with Nik Baertsch in Geneva

Join Swiss philosopher and musician Nik Baertsch as he brings his captivating funky jazz to Geneva. A fusion of sound and thought awaits!

Join Swiss philosopher and musician Nik Baertsch as he brings his captivating funky jazz to Geneva. A fusion of sound and thought awaits!

Philosophers’ ideas for music are rarely fun. Among the Swiss, Friedrich Nietzsche’s music is nobody’s idea of a good time. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s compositions hardly rate the effort to preserve them (though one did provide the signature tune for French-Swiss television for a time).

Nik Baertsch’s music, by contrast, definitely swings. But in spite of its funky drive that compares with Miles Davis’s inimitable electric period, this jazz is also thoughtful. It offers a meditation on what music can do as well as a dialogue with its listeners. Baertsch, 48, who studied philosophy, linguistics and musicology at the University of Zurich after graduating from music school, has enticingly described his group’s music as like exploring a city and “a kind of acoustical coral reef”.

“Like light in water, sounds and resonances appear in the air,” he writes in the notes to one of his CDs. “Strange creatures seem to swim by our ears. Where are we when we hear music?”

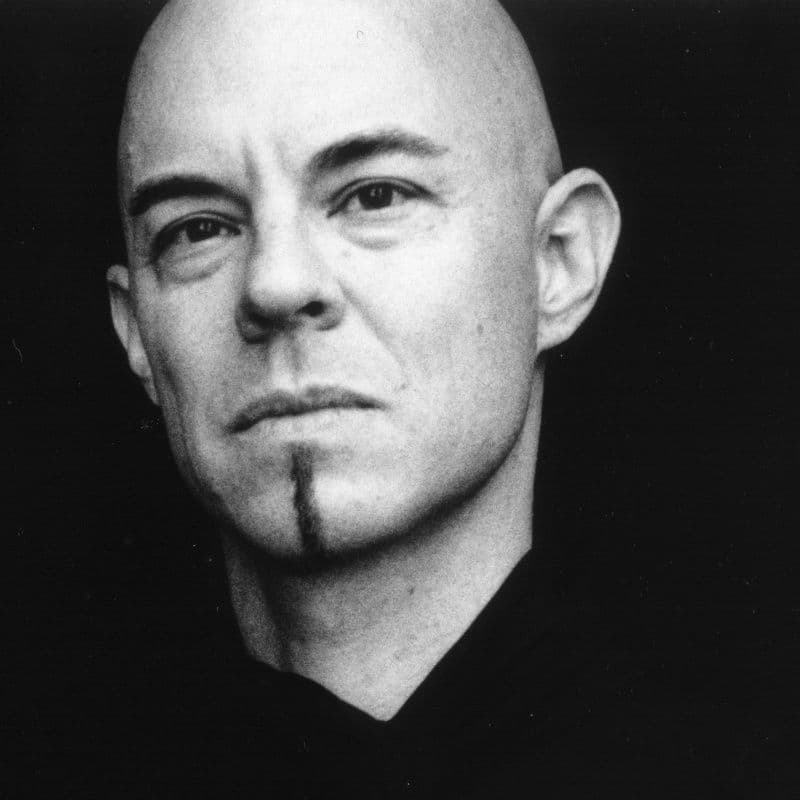

Completely unpretentious in person, Baertsch, with his shaved head, goatee beard and baggy Buddhist-monk pants, might look like a man with a message. In practice, Ronin, his musical group, seems to take as much from its audience as it gives.

Baertsch recalls that at one of Ronin’s first concerts, in an underground club, a dog began to howl just before a climactic moment. Instead of being thrown off-beat, the band “was unleashed and played its way into a trance.” More important, “the audience relaxed and became more attentive. The energy level in the room rocketed.”

He adds: “Neighbourhood dogs don’t attend our concerts much anymore.” But for Ronin, “our audiences have a similar effect on the band as a producer [does] in a recording studio.”

When I joined them in Exil on 10 September 2010, Baertsch’s uncle and the father of drummer Kaspar Rast were in the audience, and the session had a family feel. It was as if the four musicians set out to entertain each other in their home living room. Judging from the grins on their faces when they swung through some particularly intricate pieces, they succeeded.

The core of the Ronin and Mobile groups is Baertsch — on keyboards and sometimes plucking the piano strings — and Rast, a near-genius who’s up there with John Hiseman and Elvin Jones as a dancing-style drummer. Sha is the sputtering wind specialist on the formidably difficult bass clarinet, with Thomy Jordi on electric bass.

What makes Rast so amazing is his discretion. He meets every beat but he never overwhelms the other members of the group. So you may miss the complexities of his playing unless you listen closely to the drums — a good reason for buying Ronin’s CDs.

Baertsch and Rast have been friends for 40 years. I first came across their music as the accompaniment to a television filler series featuring Switzerland seen from a helicopter. It became one of Swiss TV’s most successful programmes (SwissView), [available online and as DVDs](http://www.swissview.com). Be sure to pick the blu-ray versions. The series producer paid special tribute to Baertsch and his dreamy mood music as contributing to the series’ success.

There were echoes of Nik Baertsch’s SwissView score at the Exil session. As were Morton Feldman’s meditative soundscapes, Dave Brubeck’s driving rhythms, the Modern Jazz Quartet’s more adventurous pieces (Midsömmer, for example), even Steve Reich’s pulsing works.

To me this is a sign of Ronin’s maturity rather than a failure of imagination. Earlier recordings scrupulously avoided sounding like anyone else, creating spare tonal environments that had a Japanese resonance (Ronin means a samurai without a master).

Today they are more laid back. They are willing to let in any kind of music without worrying about its integrity. Any sound, you feel, could fit. Of course that’s not true, but it is very relaxing as well as exciting to hear music that way (the Sonny Rollins approach to jazz).

Listeners who need to position Ronin’s music could call it fusion, but that label covers a multitude of sins that Baertsch does not commit. Each piece is entitled Module x (a number). The music does sound as if he has thought hard about what should logically follow the other sessions. But it doesn’t make tunes easy to identify or keep the titles in your mind. Generously he offers an 18-minute video of his latest products as well as two other atmospheric pieces on his website [http://www.nikbaertsch.com]. You can also find his agenda there.

For 4 May and 11 May Montags sessions are promised online (nos. 805-806!).

“A piece of music can be entered, inhabited like a room,” Baertsch explains. “It moves forward and transforms through obsessive circular movements, superimposition of different meters and micro-interplay. The listeners attention is directed toward minimal variations and phrasing. The band becomes an integral organism – like an animal, a habitat, an urban space. One must think with ears and hands.”

He adds: “Normally, we work in three distinct formations. The group MOBILE plays purely acoustic music, performed in rituals of up to 36 hours, including light- and room design. The Zen-funk quartet RONIN, by contrast, is more flexible and plays the compositions more freely. As a solo performer I perform my compositions on prepared piano with percussion.”

Baertsch and a business partner opened Exil in 2009 and became an artistic co-director of Zurich’s Apples and Olives festival. After the previous years intense touring and recording activities, he eased off to spend time with his family, run the club and work on the festival, as well as teaching. In 2014 he resurrected Mobile and in 2017 reconvened Ronin after a six-year gap. In May 2018 he released his latest CD of a studio session entitled Awase, which in martial arts means “moving together” (LINK).

There’s a marvellous 2008 interview with Nik Baertsch by Stuart Nicholson from the U.K.’s Observer, unfortunately no longer available online, where the composer cites James Brown, The Meters and Prince among his influences.

Global Geneva co-editor Peter Hulm is currently holed up in Erschmatt, a mountain village overlooking the Rhone Valley in Switzerland’s Canton of Valais. He spends much of his time reading, writing, editing, listening to music and walking the dogs.