Transforming Crises into Global Development Opportunities

Arthur Wood examines how current crises in development can be reframed into opportunities for sustainable solutions. Learn about innovative strategies and insights from global organizations.

Arthur Wood examines how current crises in development can be reframed into opportunities for sustainable solutions. Learn about innovative strategies and insights from global organizations.

Is the development world getting it largely wrong in the way it goes about aid targeting? Longtime development analyst and impact investing pioneer Arthur Wood, a 20-year prizewinning campaigner for better funding practices for philanthropy and social society, examines the situation today and what needs to change.(You can also read a summary of Arthur Wood’s analysis HERE)

The U.N. is bringing together development specialists to New York on 10-14 February to prepare the outcome document for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) taking place in Seville, Spain, on 30 June – 3 July 2025. Coincidentally, FfD4’s blurb also says: “amid [the] challenges there lies opportunity.” We’ll see.

G.K. Chesterton once referred to “the soft and gentle cynicism of old age [as against] the hard cynicism of youth”. International development is experiencing an undeniable crisis, and in the current climate, Chesterton’s harsher cynicism may be what’s called for.

As a person initiated into the “dark side” of development theory as a lobbyist, defence analyst, and city banker who has worked in development finance since 2005, and as a former Leadership Group member of Ashoka, the American-based citizens organization that promotes social entrepreneurship, I find it difficult to contemplate President Donald Trump’s recent actions and not be reminded of the “Ides of March”, the fateful day that marked Caesar’s assassination and eventually led to the end of Rome as a Republic.

In my career so far, I have watched development financing—including impact investment for development—claim to have mobilized trillions of dollars for development: US$5 trillion since 2015. Unfortunately, the effort has mostly had a questionable global impact.

During that time, in spite of the concerted investment, global inequality has soared from 100 million people at the top of the economic ladder possessing the same wealth as the bottom three billion, to the current situation in which less than 5 people at the top of the economic food chain have accumulated personal wealth equal to that possessed by three billion people in the lower half.

At the same time, global warming has breached the 1.5-degree limit previously marked as the maximum limit for humanity’s eventual survival. Rather than dealing with this existential threat, the current level of economic activity will increase global temperature to 2.5 degrees Celsius by the middle of the next decade. Despite the clear and present danger to human survival, the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals are, in fact, retreating in comparison to the original SDGs agreed to be achieved by 2030. They are now expected to be only achievable in the 22nd century.

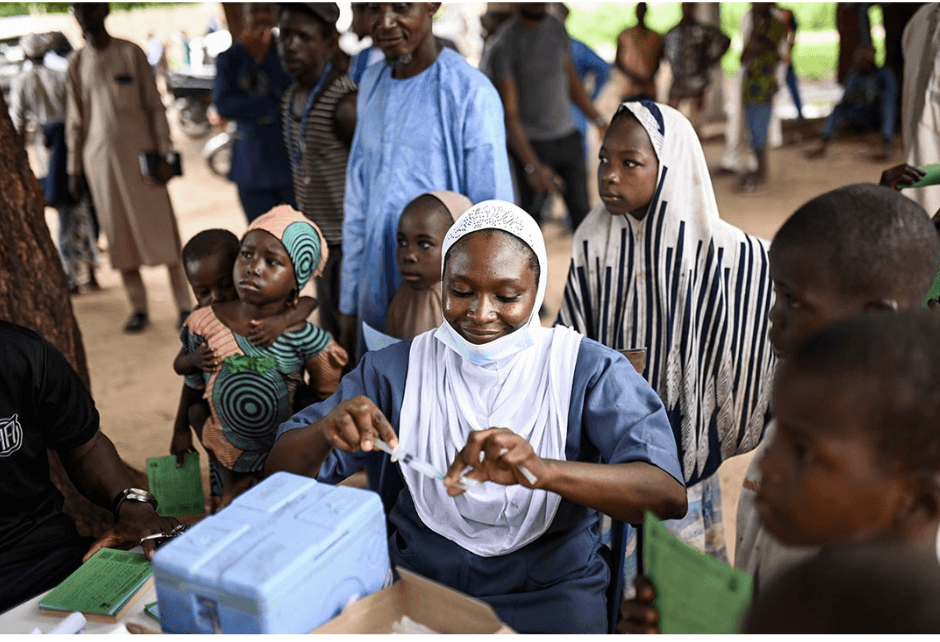

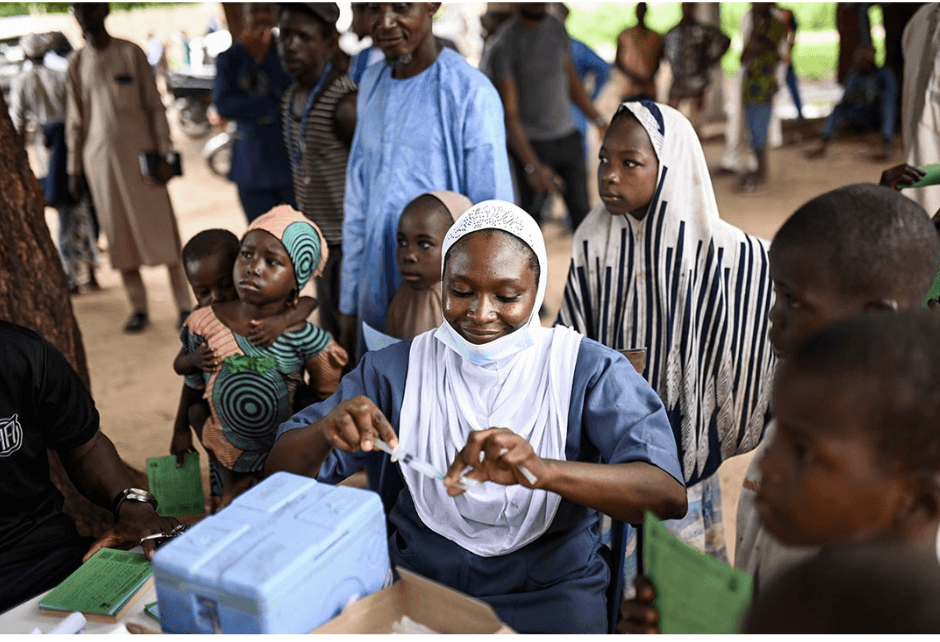

UN distribution of aid to internally displaced populations. (Photo: UN)

Development aid has had to face unforeseeable challenges, such as COVID-19, but these destructive trends were in place long before the pandemic.

It should be obvious that we face a structural fault in the current development paradigm.

The highly fragmented framing of development aid, which treats critical issues as a series of separate problems, each consigned to its own silo, or development sector, is simply not working—at least not for the people it is supposed to be helping.

The trend in development today is to base everything on an intermediary’s process and product and then figure out how we can scale it up within the silo, whether the sector involves, for example, health, tourism, manufacturing, or services. This is different from business and finance, in which a replicable client segmentation is determined first and then married to sources of capital with process and product deriving from this analysis.

In other words, development too often starts with a product that already exists that it can deliver, while business first sees what is saleable in the particular circumstances and then delivers it.

Today, silo development sectors create incentives that encourage highly inefficient social capital ‘markets’: foundations that simply do not align or leverage their balance sheets (actively use capital market solutions to fund their operations and investments), governments that focus on “blended models” that cannot provide enough of a subsidy; and for-profit venture capital / PE markets whose focus is funding focused on funding (and getting subsidies) in deals.

These models have limited potential because they occupy only a small share of the total capital market. And as any banker will tell you, the larger the scale the more sophisticated risk tools that can be applied and, critically, get to that $100m which draws in pension funds (as any Google search on the issue will indicate).

The opportunity lies in the paradox of moving from silos to aggregation – and then, as you learn on the first day of any finance course, you “follow the money”.

Government donors are cutting back…imaginative collaboration with the private sector is now more crucial than ever. (Photo: UN)

Some of this is the result of the legal mantra created by the G7 2014 Impact Investment approach, which visualized venture capitalists as principals who were part of an economic model structured to eventually produce a profit as an incentive to investors.

Innovative funding has advantages that can clearly be good, but today, at a systems level, it reinforces incentives and a culture that encourages fragmentation, lack of scale, limited collaboration, inefficient cost structures, and a demonstrable failure to mobilize real social impact, as evidenced by current SDG-, climate- and inequality-funding.

If the U.N. and the “Bretton Woods” organizations do not have sufficient capital to meet the world’s development needs, the proponents of impact investment boast that they can make up the difference, and they insist that recent growth in their sector has been robust.

Yet, if this is the case, why are nearly all the core social impact parameters — climate, inequality and economic development — moving in reverse?

The majority of impact investors are based in already developed markets, the Global Steering Group for Impact Investment(GSG) admits: that is, primarily in Western, Northern, and Southern Europe (45%) and the U.S. and Canada (34%).

Investors in emerging markets are under-represented, though with, according to GSG, “notable” presences in sub-Saharan Africa (6%) and Southeast Asia (3%).

But it sounds very much as if we are looking at existing development funding repackaged as impact investment, or corporate greenwashing framed as risk management. The lack of correlation inside each of the (ESG) Environmental, Social and Governance indices indicates that methodologies are fragmented or have been changed, and there is a lack of independent oversight.

Dealing with the elephant in the room…the polyfailures of numerous existing institutions. (Photo: UN)

To be blunt, polycrisis (the convergence of multiple crises) is matched by the polyfailures of many of our existing institutions. For example, Global Foundations, a structure invented 120 years ago, is generally regarded by bankers as an investment trust that happens to get a tax break simply by putting assets into an ordinary investment portfolio and then annually allocating 5% to social causes. At Kleinwort, where I spent time as head of Product Development, we called this the “Charity Unit.”

Coincidentally, and paradoxically, the bankers siphon off 20% of all the revenue in the sector. They take an annual 1% management fee from 100% of the funds disbursed, and 5% of this total is given away to maintain their tax status.

Because of this state of affairs, just 5% of the estimated $4 trillion of global assets in foundations needed to achieve the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are really allocated to social endeavours. This leaves 95% of foundation assets unaligned with any social mission and, at least in development terms, most are unleveraged to produce more gains.

The obvious opportunity here is that clever tax incentives, combined with conservative financial engineering, could create social investment with 20-300x more capital and social impact, and often at less risk.

This alignment is called Mission Related Investment (MRI). Some foundations are already pursuing this such as the Heron or KL Felicitas Foundations. Such initiatives need to be supported. The MRI website, for example, notes that in 2017, the Ford Foundation made a historic commitment to move beyond PRIs and allocate up to $1 billion of its $12 billion endowment over the next 10 years to MRIs.

Developing economies need a new playbook. (Photo: World Bank)

For the U.N., World Bank research indicates that if you provide replicable planning tools and funding locally – i.e. investment that goes directly to communities, empowering them as consumers and auditors of the social goods they receive – you could eliminate up to 50% of the cost of the SDGs.

At the same time, the corporate sector would benefit by eliminating a common source of corruption, that of skimming the cream off the top of social investment. Britain’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office estimated that during an Ebola outbreak in one African country up to 40% of the money went to health entities that did not exist. A recent Lancet report reported one pharmaceutical entity has reduced the unit cost of a drug from $12 to $1 – but it sold no more drugs…because once the drugs arrived at the hospital they went straight out again and were sold locally at the old price.

The answer to this is to empower the community as consumers and auditors of the goods they receive, with holistic technology that enables them to compare findings.

The biggest resistors to such a development include the large aid organizations on the ground, who would be made accountable. Disasters like Haiti, for example, have an uncomfortable way of highlighting in black and white the effect of top-down silos, lack of transparency , cost inefficiency and corruption.

In 2016 the U.N. and many governments pledged to allocate 25% of all humanitarian funding directly to communities. This was called “the Grand Bargain”. Its “Sherpas of all Signatories and the Grand Bargain Ambassadors” are due to hold their latest discussions online on 12 February, pushing forward their programme through to 2026.

After 9 years, this 25% target led to an increase of such aid directly to communities from 0.3% to just 1.2% — a long way from 25%. And then we wonder why we get political reactions against such proposals as we see today.

Building Bridges Conference, Geneva. “We are almost there!” – but are we really? (Photo: City of Geneva)

In the current development community, success is always tomorrow, never today. At a Building Bridges conference, I heard a major European official claim in reference to solving the challenge of SDGs with blended-values models — combining economic, environmental, and social factors to measure the value of an organization, business, or investment, so that risk is priced out and thus designed to draw in additional capital — “We are almost there!”

Now it is not that I am against the model at Ashoka. With OPIC (the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation), IAPB (the British-registered The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness) and Deutsche Bank we were one of its inventors back in 2006. But – instead of looking for a smarter blended model – its proponents claim that the increased leverage is possible to achieve, though it simply won’t work as configured.

Recently, a U.N. institution claimed that leverage had increased up to 18 times.

How do we square that with the fact that independent research by Britain’s Overseas Development Institute indicates that government institutions are only getting 0.3% to 1.14% leverage in the developing world, while good commercial blended models are getting four times the leverage, meaning some institutions are potentially crowding out the chance of attracting private capital?

One reason the current system is not working is that many investors are only partially committed to real development funding. At Davos, I heard a CEO claim that his company was solidly aligned with SDGs. A few days later, a member of his staff, who clearly knew nothing about development, torpedoed a $650m proposal, even though it had been supported by key development financial institutions, had mobilized the required capital, and would have had in its first year the equivalent impact of the entire UK Department for International Development (DFID) [now FCDO] budget. The financial analysis of the proposal (reviewed by hedge funds) has been based on examination of 41 billion of similar structures created over more than 35 years.

What is really needed is a Western Guarantee structure that can mobilize local currency markets for their own essential sustainable development.

Blended Value v.2 offers a systemic investment by a Western Guarantee structure that can mobilize local currency pension markets for their own essential sustainable development. It is a self-hedged foreign exchange (forex) structure using standard conservative assurance accounting methods, and can get at least 20 times as much leverage.

In other words, a given amount of seed capital can leverage 20 times as much investment capital. The mathematics of such investments? A development finance institution that offers a $25m subsidy can mobilize $1bn within 7 years, offering more than a 20% internal rate of return. All of that can be done at 70% less risk than a traditional blended-silo structure.

When systematic thinking was applied to the international vaccine alliance, GAVI, which relies on both public and private investment, the unit cost of vaccinations dropped from $50 to less than $1.50.

Community-driven models such as the Aga Khan Foundation have had equally impressive results. AKDN’s socially aligned investment now employs 96,000 people and has a turnover in excess of $4bn per annum. Its ambitions for change are truly system-changing.

Some organizations are doing it right. (Photo: Agha Khan Foundation)

In finding solutions for impact investment, it may be better to focus not only on asset silos, but also on what we all intuitively know to be interrelated systemic issues.

Unfortunately, this is not how we currently fund or manage risk.

Nevertheless, in the replicable scale of systems intervention now facilitated by technology lies the opportunity to mobilize “billions to trillions.”

We need to look to larger market opportunities such as collaborative systemic outcomes using as we do in the private sector – securitization, equitization – using perhaps tax-incentivized contingent payments — as we even know the future value of these sequenced interventions.

Creating tradeable systems equity – at the level of a city, region, small island developing state or maritime region – such as the Med – would unleash public equity markets and pension funds within a transparent frame in which all the stakeholders are incentivized to work together as equity holders. Structured intelligently, such initiatives would give private investors the same tax breaks for making a for-profit investment as if they would for a grant.

The value has already been calculated by McKinsey, World Bank, Accenture et al. It’s measured in hundreds of billions of dollars. And the quicker the changeover the higher the returns.

As a result we can calculate a “marginal social cost of capital”, where governments know for each dollar, euro or Swiss franc spent how much economic, social, and political value has been created by a subsidy. As New Economy models have shown, when the model scales up, the unit cost drops, and predictability increases.

The center-right can also see this as a much larger commercial opportunity. It provides the soft power tools for the West to do what they want: win Cold War 2 — the realignment of global power that is now underway. Let us not forget Vietnam was lost militarily, but the original Cold War was won by hard and soft power together – by genuinely winning hearts and minds. Very simply stated, the current tools are not fit for purpose – and strategically – who will use these tools?

The current crises offer an opportunity to look anew at development, to reframe and modernize how we finance the survival and development of humanity in both its senses. The tools that date back 80 to 120 years ago demonstrably cannot work. And they are clearly not working.

If we apply technology, finance, and legal innovation to development – as they have been applied to other sectors of the economy – we can create incentives for collaboration and scaling up our operations.

This could be a win-win proposition for all of humanity’s stakeholders and one that may even reverse the current trend of political polarization. Let us not forget the lesson of history. The last time technology drove polarization, it led to the bloodiest wars in European history.

Shakespeare crystallized today’s opportunity when he wrote: “There is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life Is bound in shallows and in miseries. On such a full sea are we now afloat.”

The choice is clear: we can continue to rely on the current paradigm while doing nothing to change it, or we can work to correct the situation by adopting a new approach. If we continue as we are and keep on pretending that the current system is working, we have to adopt Monty Python’s Life of Brian advice on crucifixion: “Always look on the bright side of life /[and] Always look on the bright side of death.”

Arthur Wood has carved out a decades-long distinguished career in development analysis and practice, now with Total Impact Capital in DC and Equity4Humanity at the Geneva Center for Security Policy, where he also co-chairs a Catalyst Task Force on mobilizing large-scale capital. A former Leadership Group Member of Ashoka, he is both a chosen TBLI Hero (TBLI is the world’s leading ESG/Impact Investing network/authority) and also a Sorenson Impact Foundation Fellow in recognition of his work. His biography for the Responsible Finance and Investment Summits also notes: “He is married to a Norwegian who works at the UN with three blonde older children and a black Labrador — all of which requires an English sense of humour.”

What is Next after the L.A. Fires

Remembering Jimmy Carter

Syria: A Bit of Historical Perspective

United States: It’s Not Just the Economy

From LA to the South of France: Combatting wildfires with global solutions

Moscow Attack Marks Return of ISIS

Forgotten Yemen Forces the US and the World to Pay Attention

Middle East: Inching Toward Armageddon

What Can Israel Do Now?

Ignoring World Opinion, Israel Steps into a Hornet’s Nest in Gaza

Biden’s Visit May Have Kept Gaza From Boiling Over

Hamas Attack Shocks Israel and Invites Massive Retaliation

The Real Cost of Ukraine

The Coup in Gabon: Just Another Incident in a Global Powershift?

On Bullshit, lies and politics: Dealing with mis/disinformation

80 Is the New (…Um, I Forgot)

Derborence: from disaster zone to birders’ paradise

Jacob Collier: accidental superstar

The Gold of Sudan and Good Old-Fashioned Russian Colonialism in Africa

The Protean Self