Yazidis: Resilience and Recovery Post-Genocide

Discover the profound journey of the Yazidi community as they rebuild their lives post-genocide, highlighting their cultural resilience and quest for human rights.

Discover the profound journey of the Yazidi community as they rebuild their lives post-genocide, highlighting their cultural resilience and quest for human rights.

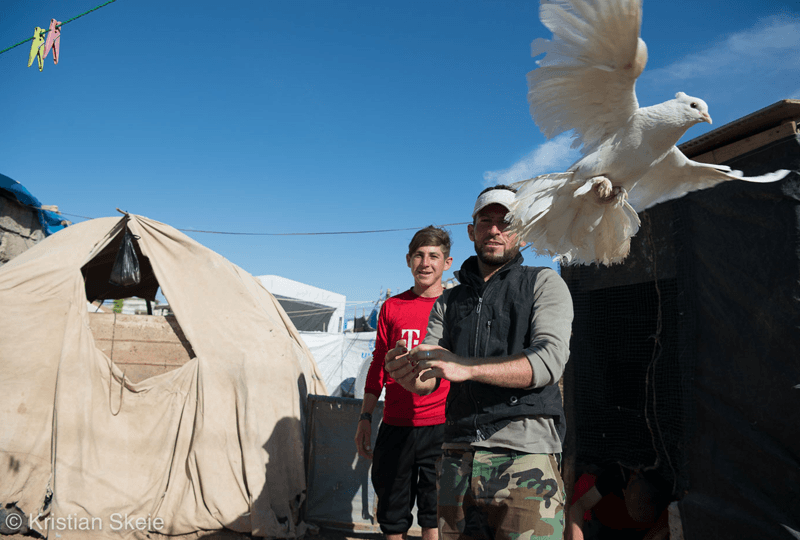

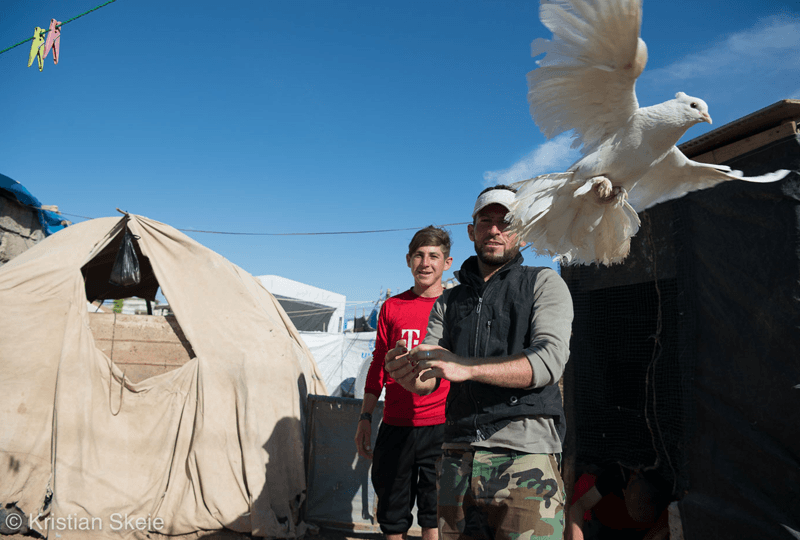

Hajji Mirza is from Tel Azar. Now he and his family are condemned to live in a tent in Khanke, a refugee camp with over 16,000 people near Dohuk in northern Iraq. “For 20 years I worked as construction worker in Tikrit. For 15 years I did the same in Kurdistan. We did not ask for government positions, we did not protest, all what we want is to continue our way of life. In spite of all that they keep killing us.”

Hajji Mirza is lucky because he lives inside the camp, where local authorities and international relief agencies provide basic services as there are thousands of other, less fortunate, families scattered over the hills and fields and on the outskirts of Khanke who must cope on their own. We entered a tent as its inhabitants were washing the ground. Unable to enjoy the benefits of a real camp, they lack even the most basic services. Written by hand on the canvas next to the entrance are the words: Ya khowdi, wa ya malek tawoos (Oh God, and oh Peacock angel). Next to this, the fateful date: 3/8/2014.

On that day, in the early hours of August 3, 2014, ISIS (also known as Daesh) fighters with heavy weapons from Ba’aj, who had conquered Mosul two months earlier, attacked the Yazidi villages of Girzarek and Siba Sheikh Khidir. Until then, the Yazidis had been protected by Kurdish Peshmerga forces, but these withdrew on receiving orders from above.They did not evacuate the Yazidi civilian population, leaving them defenseless and at ISIS’ mercy. Local Yazidi resistance armed with light weapons collapsed after four hours; they did not have enough ammunition, nor heavy arms to resist the Jihadis in their armoured vehicles. ISIS forces quickly entered the town.

Panic-stricken, the population tried to flee to nearby Mount Sinjar. Some were lucky, many not and ISIS captured the unfortunate ones: men were forced to convert to Islam and those who refused were killed on the spot. More than 35 mass graves have been found so far. But the horror didn’t stop there and perhaps the dead were luckier than those who survived. ISIS revived open sex slave markets, a tradition that had disappeared from the region with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century. Thus, after the fall of Girzarek and Siba Sheikh Khidir, some 5,240 women and girls were captured, eventually sold as slaves.

Invited into the tent, we found ourselves sitting opposite to a woman – call her Amal – who narrated her ordeal. She could be 45 years old, but it was difficult to tell. A life of hard work under the Iraqi sun has shriveled her skin. Next to her is her daughter, an infant in her lap, and her two sons, 11 and 14 years old. They lived in Kojo, a village south of Mount Sinjar. “Back then we lived normal lives,” she says. “We were satisfied.” When ISIS attacked her village early one day, they killed one of her daughters. The woman survivedwith her other daughter Nisrin and two teenage sons, but together with dozens of other family members, they were taken hostage. The Daesh militants forced them to convert to Islam and to read the Koran. When an old woman refused, they immediately shot her. Yet, converting did not protect them from the worst of suffering.

“The first group that attacked Kojo were local Arabs,” Amal continues. “They separated the women from the men, and took us to Sinjar city. They mistreated us, left us without food for ten days. Then, they separated us to small groups of 10-15, and one of them started selling us to others, and sent us to different places.” Amal was taken to Mosul where she stayed for a month, before being moved to Tel A’far where she was kept captive for another month, before being sold yet again. This time, they sent her to Raqqa where she languished as a slave for yet another month. ISIS often kept her at their military headquarters, one of the worst places to be hostage, given the constant mistreatment and abuse by large numbers of militants passing through. When she sought to resist, one of her captors struck her on the head with the butt of his rifle; the wound bled for a month. Amal still has pains and memory gaps. She urgently needs treatment and medication, but does not have the money.

Given the discreet expressions of pain on her beautiful face, Amal clearly finds it difficult to tell of her suffering to strangers, particularly in front of her three children. “They treated us better in Raqqa,” she continues nonetheless after a moment’s respite. “They gave us food to eat and proper water to drink.” She managed to escape thanks to the assistance of a Syrian woman. Her sons managed to flee with another group of women. But 30 members of her family remain hostages at the hands of these ISIS militants, including her 10-year-old nephew from whom they had news two weeks earlier. Amal receives news of these relatives, but not necessarily good news. She shows a photo on her mobile phone; it is an ISIS propaganda photo and in it the young nephew is shown holding an old Kalashnikov rifle that looks huge next to him, while his other hand points a finger upwards, the jihadi sign of tawheed – or unity of the creator. Amal’s nephew is one of the captured Yazidi boys that ISIS is now training as killers.

DEPARTURE COULD ELIMINATE THE YAZIDIS

AS A COMMUNITY

“All Yazidis want to leave, in a generation none will be left in Iraq,” says Falah, a pharmacist, now a displaced refugee in his own country. Falah receives us in his family’s newly-built house, a house withbare walls. We sit with him on the ground; from behind a curtain, we hear the women of the house preparing food. Indeed, Yazidi hospitality never ceases, not even when things are dire. As proof of the matter if further proof were needed, Falah’s daughter, barely two years old, is crying. Every time he leaves to go to work, Falah says, she cries. Falah has another daughter who is three, but she is gone. His wife took her, together with three of his younger brothers last December, crossing into Turkey and then risking the precarious boat journey across the Aegean Sea to reach the eventual safety of a refugee camp in Germany.

Why did he let her family embark on such a dangerous trip in the middle of winter? “Because we heard that the corridor for refugees was going to be closed, we thought it was our chance.” Then why didn’t he join his wife and daughter? “Because I did not have enough money to take all my family, including my aging parents. Now I am working to join them.”

It is difficult to understand why people take such risks. The only way to grasp this is by linking it to their utter desperation, and the complete lack of tangible hope. Yet for Falah, ISIS is only part of a bigger problem, notably the systematic and often violent discrimination levelled for centuries against the Yazidis because of their religion.For some, their beliefs are associated with mystical Zoroastrianism and Sufism, while others argue that it has more to do with a combination of Shi’a and Sufi Islam mixed with pagan folklore and sun worship, “We are a drop in a sea of Muslims which wants to suffocate us,” he says. His friend Ali, originally from Durkeré and now living in Dohuk, adds: “We could never imagine something like this could happen. In 2003 (during the American invasion of Iraq) many Sunni Turkmen from Tel A’far, a Baathist stronghold, found refuge in Sinjar, and we welcomed them.

But the good will was not reciprocated. Far from it. As far as the Sunni Muslim can see, the Yazidi are not “people of the book”, that is a people inscribed in the Abrahamic tradition. From the ISIS perspective, Yazidis do not own a holy book; the Yazidi sacred texts, contained in their Kitêba Cilwe (“Book of Illumination”) are not recognized by Fundamentalist Islam as worthy of respect. This single track fanaticism leads naturally to extreme notions and equally extreme inhuman actions, “Therefore they have the right to kill us men and rape the women.” says Ali ruefully.

In the village of Duguré, where heavy fighting took place prior to the defeat of Daesh fighters, the retreating militants blew up 417 houses. On the wall of one of them, where Jihadists had evidently lodged, there is graffiti with the words: Ya ‘abdat al-shaytan, bildabh’ ji’nakom (Oh worshippers of the devil, we came to massacre you).” But who is the real personification of Satan?

The Yazidis feel doubly wounded and betrayed. Their neighbouring Arab tribes attacked them, the Kurdish Peshmerga abandoned them, and the “international community” ignores them. The question now is whether this extraordinary religion, civilization and unique way of life that has survived for centuries, will outlive the ISIS genocide? Many, such as Falah, are pessimistic. They think the Yazidis will seek refuge in countries far away from their historic temples. But as Ali points out, the Yazidis have been victims of massacres and forced conversions many times before. “Yazidis call the 2014 events a farman, a term that comes from the late 19th century Ottoman massacres of religious minorities. In previous farmans, converted Yazidis remained Muslim. This time, they returned to their Yazidi religion.”

Vicken Cheterian is a Geneva-based journalist and author. His latest book is: Open Wounds: Armenians, Turks, and a Century of Genocide (C Hurst, 2015). He travelled as part of a Webster University (Geneva) research assignment to northern Iraq with Norwegian photographer Kristian Skeie.

NOTE ON THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Kristian Skeie (kskeie@gmail.com) is a Norwegian, Swiss based documentary photographer and contributor to Keystone Photo agency (www.keystone.ch) Zurich. His main work has focused on the aftermath of war, specifically life today in Srebrenica (Bosnia), Rwanda and Iraq. He seeks to depict the story of how people are resettling in Europe, notably Germany and Sweden, following their war or genocide experiences. He is currently working on a new project on the impact of Middle East migration in the Balkans. Skeie is also collaborating with various NGOs, companies and media partners, notably on an initiative exploring new technologies for amputations and the reconstitution of nerves in the body. For further information, see: http://ks-imaging.blogspot.com and https://www.facebook.com/photographerkristianskeie