The following is a summary of the long-read analysis by Arthur Woods. (SEE LINK)

Is Development Aid Failing? Despite ambitious efforts, the global development sector appears fundamentally flawed in its approach to aid and funding. Mobilizing over $5 trillion since 2015 has not prevented deepening global inequality. The five richest individuals now hold as much wealth as half of the global population, and climate change continues to escalate past 1.5°C of warming, with projections indicating a rise to 2.5°C within the next decade. Meanwhile, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), initially targeted for 2030, are unlikely to be met before the 22nd century.

The UN is convening development experts in New York from 10-14 February to prepare for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in Seville, Spain. The conference’s tagline states: “Amid challenges, there lies opportunity.” But will this be more than rhetoric? The international development sector operates within rigid silos—health, education, and infrastructure are funded separately rather than through integrated solutions. This disjointed approach leads to inefficiencies, duplicated efforts, and wasted resources. Development efforts often impose solutions onto communities rather than designing interventions based on their needs. In contrast, businesses analyze market demand first and tailor solutions accordingly. The development sector must embrace a similar client-centric approach to ensure aid interventions are effective and sustainable.

The sector is also hindered by misaligned incentives. Foundations allocate only 5% of their endowments to social causes, while governments focus on underfunded “blended finance” models. Meanwhile, private equity markets chase subsidies rather than real impact. Impact investing is frequently touted as a solution, yet most investments remain in North America and Europe, with only 6% directed to sub-Saharan Africa and 3% to Southeast Asia. ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) metrics lack standardization and oversight, allowing greenwashing and financial repackaging to replace real impact.

Systemic failures in development finance exacerbate global crises. Despite controlling an estimated $4 trillion in assets, foundations invest most of their endowments with no social mission. A “polycrisis” of global challenges—inequality, climate change, governance failures—is met with a “polyfailure” of institutional responses. Even well-intended initiatives fall short. In 2016, the UN and governments pledged to allocate 25% of humanitarian funding directly to communities—a commitment known as the “Grand Bargain.” Nine years later, only 1.2% of aid reaches communities directly. This failure fuels skepticism about the effectiveness of development aid.

A path forward exists. Some foundations, such as Heron and KL Felicitas, are pioneering Mission-Related Investments (MRI), leveraging their endowments for impact. The Ford Foundation has committed $1 billion of its $12 billion endowment to MRI over ten years. Additionally, financial models exist that could generate 20 times the leverage of current aid structures. A $25 million development finance subsidy could mobilize $1 billion within seven years while reducing risk by 70%.

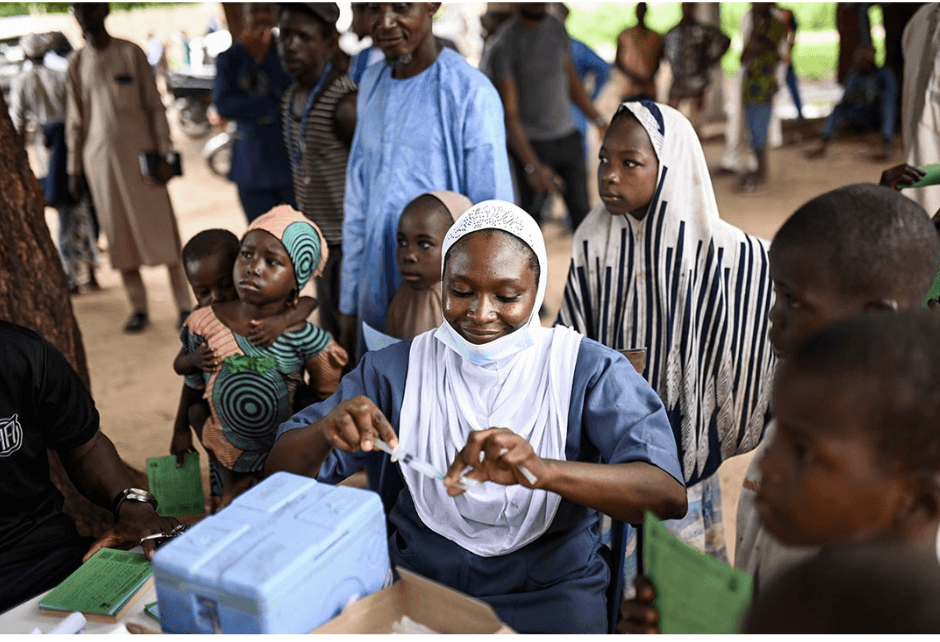

Instead of fragmented, siloed funding, a Western-backed guarantee system could unlock local currency markets for sustainable development. “Blended Value 2.0” could use structured financial instruments—securitization, equitization, and tax-incentivized contingent payments—to mobilize capital at scale. Success stories such as GAVI, the global vaccine alliance, which reduced vaccine costs from $50 to $1.50 through a systemic financing model, and the Aga Khan Foundation, which employs 96,000 people and generates over $4 billion in annual revenue, demonstrate that social investments can achieve both impact and financial sustainability.

Development finance is not just an economic issue but a geopolitical one. A well-structured financial system for development could serve as a crucial tool in global power realignment, providing an alternative to coercive economic diplomacy. The West won the Cold War through both hard and soft power—now, it must leverage systemic impact investing to remain competitive in Cold War 2.0.

The crises we face present an unprecedented opportunity to rethink development finance. The outdated models governing aid today are no longer fit for purpose. By integrating technology, finance, and legal innovation, we can create incentives for genuine collaboration and large-scale impact. Shakespeare put it best: “There is a tide in the affairs of men, which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.” The time for action is now. We can either continue pretending the current system works or embrace the opportunity for systemic change. The choice is ours.