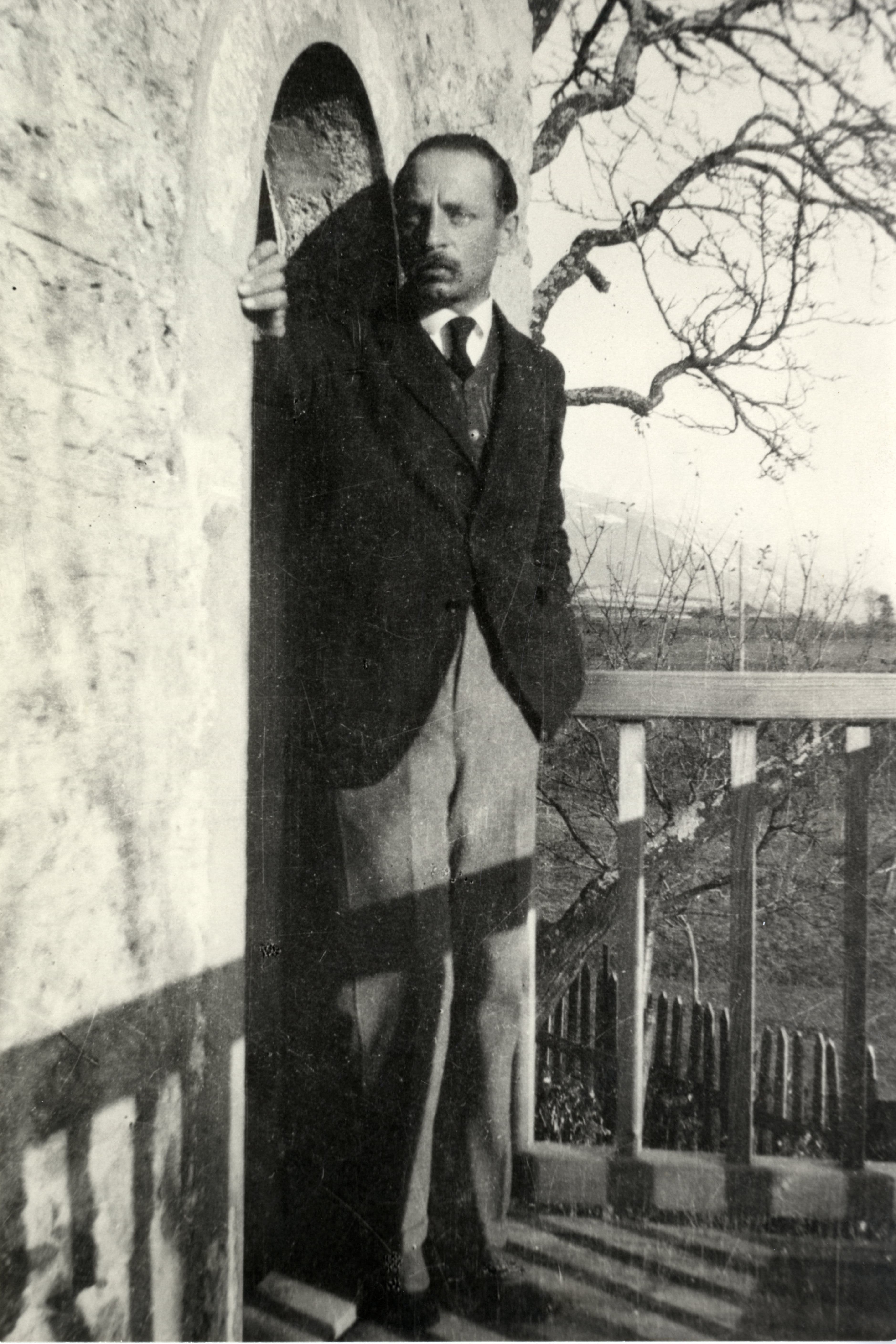

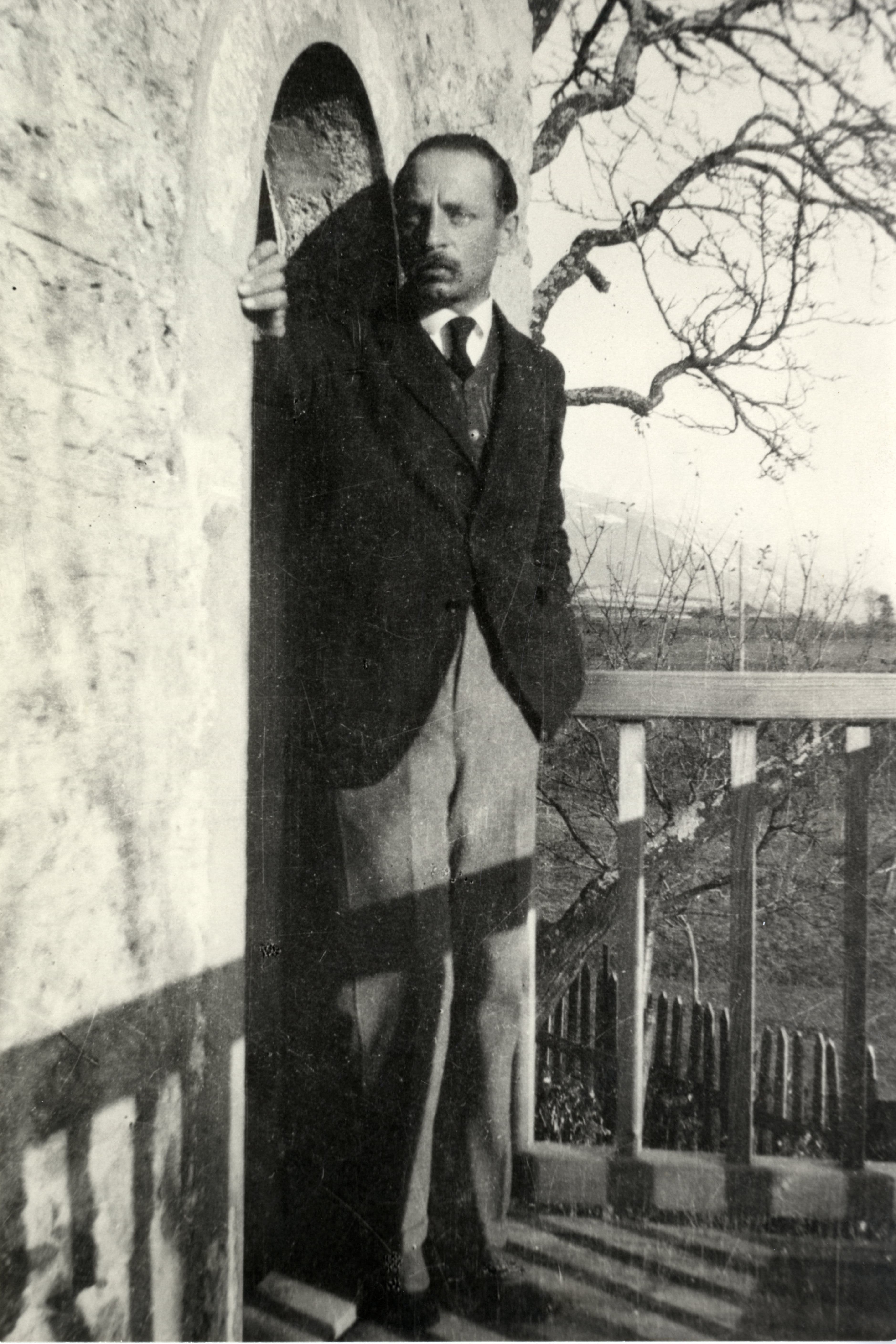

Rilke in Valais: Rediscovering Swiss Inspiration

Discover how Rainer Maria Rilke's perceptions of Switzerland evolved during his time in Valais, igniting his creative spirit and connection to Swiss culture.

Discover how Rainer Maria Rilke's perceptions of Switzerland evolved during his time in Valais, igniting his creative spirit and connection to Swiss culture.

Until he saw the Valais, Rilke was somewhat dismissive of Switzerland. He wrote to friends from Sils, where Nietzsche found refuge 50 years before, that the “stupid” mountains were no more than “imposing barriers, as senseless as some barred door”. The fields of snow struck him like a white desert and banal tourist bait. Travelling through Switzerland to Italy, Rilke would draw the blinds of his carriage. He found the scenery of mountains and lakes “contrived”, with God the stage-manager “directing the spotlight of sunset onto the mountains”.

Geneva he spared from his disdain. The city in 1919 reminded him of his beloved “incomparable” Paris “in the atmosphere, the street scenes, the set of the houses”. But it was also where he renewed friendship with a Paris acquaintance, Baladine Klossowska, mother of the painter Balthus, a woman 11 years his junior who became the last great love of his life. Separated from her husband, she lived in the rue du Pré-Jerôme, off the rue de Carouge.

A rootless cosmopolitain

Rilke was 40 when he came to Switzerland in the aftermath of the First World War, a rootless cosmopolitan, already acknowledged as a great poet known for his anti-war sentiments. He had good reason to believe he might be in danger from the “White Terror” sweeping through Munich. He had signed Thomas Mann’s “Appeal against Arrogance” calling for cooperation between the classes. Even worse in the eyes of Germany’s proto-fascists, Rilke had given shelter for one night to the poet Ernst Toller, who one month earlier had been declared Chairman of Bavaria’s ‘Soviet’ Republic and was now on the run before his capture and imprisonment.

At first Rilke saw Switzerland as no more than “a waiting room” before he set off for his real life. It appeared unrelated “either to my past, or to the future”. His permit was only for 10 days. Swiss authorities in this period were not keen on granting entry permits for people from crisis zones — what else is new? But the poet’s contacts included some old-established Swiss patrician families. By 11 August 1919 he was telling his correspondents: “I praise and praise the instinct that has led me here.”

The war had inflicted on him a great “dumbness”, at least by his standards. It was five years since he had been able to work on what became the Duino Elegies. Nevertheless, he had hopes that somewhere in Switzerland he could find a place offering the right conditions for him to work once he had been able to “spin himself into his cocoon”. “Everywhere there was a promise of the future,” he wrote. “Like a sample of material from which one later gets a complete dress, a cloak with a hood to make one invisible.”

But this invisibility was nowhere to be found in the more urbane regions of Switzerland. “Quiet, and the particular care I need, nature, solitude, no people for half a year!” he lamented in 1920. “When will this come? And where?”

When he made his first public appearance in Zurich in October 1919, an audience of 600 people turned out for his poetry reading. His biographer Donald Prater, a New Zealand professor before becoming a translator and minute-writer at the CERN particle physics laboratory, notes: “For all his tendency to disparage the Swiss and the artificial beauties of their country, [Rilke] was learning to appreciate the virtues of a solid and regulated bourgeois existence he had never known; and it was dawning on him that this multinational and multilingual society might offer the lifeline he needed.”

Nearly a century on, it’s hard to grasp exactly what made him so personally mesmerizing, since we no longer hear his strong baritone voice and theatrical recital of his poems. Is it enough to list the influential men and (mainly) women who supported him financially and materially in later life? Or to learn of his dependence on others to keep him in cigars, wine and accommodation in desirable residences?

Read how he described Balthus’ mother, known as Merline, the only person with whom he thought he would be able to achieve a balance of love and work: “M. is one of those people who, having once received a payment at some counter, keep coming back to it even when the official assures them nothing has come in under her name,” he wrote to someone else.

Even momentary irritation makes it hard to justify this description of the woman who helped him set up his last refuge. In fact, she had respected his need to be alone, and he was the one who chased after her or called her to him.

Prater admits to Rilke’s snobbery and pride in penetrating the “hard and dense material” he considered the Swiss establishment. Almost immediately he was offered a 17-century manor house north of Zurich for the winter. “No poet ever had so smooth a path to ideal condition for his work,” observes Prater. “Every detail of practical life was settled without his having to lift a finger, even to a supply of wine, cigars, and cigarettes.” In fact, the winter he spent there was “wasted and lost”, writes Prater, compared to the writer’s creative hopes.

An artistic sponger

On this account, Rilke comes across as the worst kind of artistic sponger, using his “letter factory” to keep people away while leaving them dangling on his emotional hook with effusive words. He dropped correspondents for years when they were no longer of use.

He appeared profligate with money, buying rare books and perfumed water though perennially short of cash. His anti-rationalism and reliance on “poetic” intuition made him appear indecisive while he waited for inscrutable signs to tell him what to do.

To rent and then buy his final Swiss home, he relied on a well-placed Swiss, Walter Reinhart, and the man’s female cousin, Nanny Wunderly-Volkart. This key element of the Rilke legend was the Château de Muzot (the t is pronounced, as he noted) just outside Sierre.

Rilke: A preference for Geneva

The Valais wasn’t his first choice for a home. After the winter of 1920 spent in the Ticino, Geneva had never appeared “so radiant and blowing and open”, he wrote. From his room in the Hotel des Bergues the city, lake and “graduated tiara” of the Salève and Savoy Alps “were bathed in a clear light through which Paris and France seemed to waft over him,” Prater observes.

His long-time friend Princess Marie von Thurn and Taxis came to visit her grandchildren at school in Rolle. Rilke stayed in a rose-covered former priory turned pension in the lakeside town of Etoy, which he found so pleasant he searched for long-term accommodation in the canton of Vaud, but without success.

This sent him back to the Valais, where he had briefly stayed on holiday in October 1920 with Merline, along with Merline’s husband and a zoology professor and his wife in what was then the Hotel Bellevue in Sierre. He found the canton outstandingly beautiful, the mountains no longer “importunate” from the Rhône Valley. The countryside was reminiscent of Provence and Spain but “a little less fanatical, a little more conciliatory”.

On 28 June 1921 Rilke and Merline came back to the Hotel Bellevue. “This remarkable Valais”, Rilke enthused as they looked for a home, for him rather than both of them.

The legend of Muzot

How he found the Château de Muzot has become a legend. After a number of disappointments the couple were about to give up and return to Etoy. Strolling the Sierre streets on their last evening they saw a photograph in a nearby hairdresser’s depicting a 13th-century château-style tower “for sale or rent”.

When they inspected it the next day, they found a small, step-gabled tower with a small garden a couple of kilometres above Sierre on the road to Crans-Montana. Belonging to the hairdresser’s mother, it had water only from a well, no electricity and primitive sanitation. But it could be “peut-être mon Château en Suisse, peut-être,” Rilke noted.

Even better for Rilke’s intuitive senses, certain species of birds, flowers and butterflies were found nowhere but in this “noble contrée” (region of vineyards/vignobles), in Provence and in Spain. At the road junction below the Château de Muzot, a poplar stood “like a symbol and an exclamation mark, as if to say, and to confirm: this is it!”

The couple had the prospect of keeping their Ticino villa, where they could have lived more cheaply and the summer would have been more settled for Merline. The Muzot’s owner, also, was ill and they could not come to an agreement. Then Walter stepped in and made a six-month offer for the rent. Merline moved in just after mid-July while Rilke “still nerved himself in the hotel for the test”.

His partner made Muzot cleaner and airier for him. Uncertain how things would work out, Rilke asked Nanny only for what seemed essential: “candlesticks, pillows, a storm lantern (though of course she was thoughtful enough to send a host of other things equally necessary which he had not thought of),” Prater notes in A Ringing Glass: The Life of Rainer Maria Rilke” (1986).

Merline showed phenomenal energy and enterprise, Prater underlines. “She was adept at improvisation and obtaining local advice and help, and the old house gradually took on a liveable air Rilke would not have credited.”

On making Muzot his home

Rilke described taking over the tower as “putting on a suit of heavy armour”. Since you can’t visit the still private property, it might be useful to describe it when Rilke took residence. The ground floor, Prater records, was reached through the veranda porch. It took you into “a spacious dining-room with a traditional Valais stone stove and a fine 17th-century oak table.”

“A tiny salon alongside opened to a balcony with a view across the Rhône valley; and there was one small bedroom, and a kitchen built on more recently to replace the original cellar-kitchen […] These were Merline’s quarters.

“On the first floor was a square room [whose ceiling beams indicated 1618 in Roman numerals] which he took as his study. […] It was not overgenerous towards his habit of walking up and down while he walked,” Prater remarks. “Its windows looked to south and west to the distant majesty of the Valais Alps.

“Adjoining it was a bedroom for him, tiny, with an archway door onto a small balcony, and off that again a small whitewashed chamber, the so-called ‘chapel’, entered also from the landing through a low medieval doorway above which stood in relief, not a cross, but a swastika.

“There were further attic rooms above, with loophole windows only. Thus his isolation could be ensured, ‘independent of the comings and goings and the running of the household’.”

Nevertheless, the living conditions “remain somewhat demanding and rough” (héroïque et rude). Nanny Wunderly undertook to meet his housekeeping costs. She even found a 26-year-old farmer’s daughter from Solothurn, Frieda Baumgartner, to do the work. Merline’s presence proved handy. She took on the necessary training for Frieda. A new stove was installed in his study, courtesy of Werner Reinhart, along with a new kitchen range and a “splendid wing-chair” from his patron. The suit of armour became a cloak, Rilke discovered, “somewhat stiff, but nevertheless rather softer”.

Rilke’s letter factory at full steam

His letter-writing factory, “in full-steam production”, turned out 180 pages in one week, he reported on 1 December 1921. Here he discovered the true greatness of Switzerland, “this generous and so unused landscape”.

But on 1 February he complained: “Concentration is terribly hard. Even eating is a distraction, and the hours between meals seem too short for anything whole to be done. If only one could eat for half a year, and then spend the other half meditating, so that there did not have to be this constant shifting of focus.”

The next day, as unexpectedly as at Duino, he began to write poetry of his own, rather than translations or essays – the Sonnets to Orpheus. In three days he completed 25 in a free version of the classic form.

He wrote them at his standing desk. Then a second desk arrived from another of his female patrons, and on this he took up the neglected Elegies again. “I went out, in the cold moonlight, and stroked my little Muzot like a big animal – the old walls have granted me this,” he told his publisher.

On 23 February he completed the Sonnets in the final form of 29 poems. Free to look outside himself again, he began to interest himself in improving the garden. He was delighted by the prospect of “a host of roses, a whole people of roses, the rose-miracle”. On 12 May Reinhart’s offer for Muzot was accepted and Rilke signed the purchase contract a week later.

The splendour of Valais, gentle shadows, its purity

Merline was now living in Berlin with her sons. He invited her for July. “You must become the painter of the Valais,” he wrote. “What splendour, the gentle shadows, the purity of this country’s ‘traits’… but who am I telling?” He installed her on the upper floor but by October he was writing to Nanny: “Solitude is the only possible thing for me. Anything else must be the exception. Muzot is like a mold for one living being only. With two it’s overfilled.”

Now you know the worst of Rilke’s character judged in a cold light. In truth, he spent many days helping Merline and her sons over the years, writing letters to people who could aid her and accompanying her back and forth on her travels. He made over large amounts of his earnings from the publisher to his estranged wife and their daughter. And none of his benefactors complained of supporting the great poet in these years.

There’s a human side to this flood of creativity, too. Sonnets to Orpheus poured out when Rilke learned that a playmate of his daughter in Munich, had died at 19 in the year after the 1914-18 war. On New Year’s Day 1922 he received from her mother an account of how the talented dancer, musician and artist had suffered and died from glandular trouble. Her spirit “controlled and impelled” his inspiration, he wrote.

As for his charm, when the housekeeper Frieda was returning home, he presented her with an expensive bottle of perfume. Frieda said she would have to hide it from her sister Rosa, who otherwise would be envious. When he saw Frieda off, however, she found he had bought another just like it for her sister, too.

A gesture of literary kindness: Le Noyer (The Walnut Tree)

A little later, Rilke went to a small chateau which a long-time woman friend thought of renting nearby. The wife of the doctor who owned it showed them round and they took her to tea afterwards at the Bellevue. She knew no German, and was unaware of his fame, but was captivated by his courtesy and charm, Prater records. Two years later, she asked him, having since heard he was a great poet, to write some verses for her in French, perhaps about her walnut tree.

Rilke smiled and said he did not usually write to order. A short time later, when she was invited to dinner at Muzot, she found by her plate a carefully written holograph, with a single rose on the napkin. The poem was entitled “Le noyer”.

Appreciation for other cultures permeated his life and thought. Though the Duino Elegies recount his progress from celebrating a “terrifying” Angel to a “consentient” one, an almost Buddhist conception, his Angel , he said, “had nothing in common with the figures of the Christian heaven – if anything it owed more to those of Islam: it was there merely to symbolize the complete transformation of the visible into the invisible ‘higher form of reality’.”

Prater, the CERN employee, even finds Rilke’s poetic intuition to have brought him close to the quantum theory of atomic physics in the writer’s conviction that “the threads of all forces and all events, of all forms of consciousness and of their objects, are woven into an inseparable net of endless, mutually conditional relations”.

Imperial Germany: almost an embarrassment to writing in German

Rilke’s distaste for imperial Germany made him almost ashamed to use the German language. André Gide remembered Rilke remarking in 1914 that German had no expressive word for the palm of your hand compared to the French la paume “which tells of the whole mystery of man”.

How much of Rilke’s personal misfortunes came from the disruption of combative imperial powers? He was born a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, forced to take a Czechoslovak passport with the collapse of the old world, though Prague for him had been a city of dark streets that made him long for sun.

The 1914-18 war destroyed or permanently disrupted so many lives for those who survived and the rampant inflation in Germany afterwards made it impossible for its greatest modern lyric poet to find the peaceful solitude he craved. The Muzot years are filled with anecdotes of his helping friends whose German marks were becoming more worthless by the hour.

Despite his change of nationality, to his friends Rilke became René again (his birth name). Rainer was simply the forename his first lover Lou-Andreas Salome had insisted on as a “plain German” name.

In Muzot, Rilke also found himself writing poems in French “dedicated to the Valais, true ‘Quatrains valaisans’”, which he would use “to support my future application for Swiss nationality. There is no better proof that I have this country in the blood.” He spoke of the collection as a “verger” (orchard), for which he found no adequate German synonym.

He had not written such ‘regional poetry’ for nearly 30 years. Prater describes them as an affirmation of allegiance that seemed to eclipse what he felt to France: “so heartening for me as they sprang up in the language of the country to which I owe so much”.

Another batch of poems in French came in 1923 while staying in the luxury Savoy Hotel in Ouchy with its view over Lake Geneva. There were more than 20 on the cherished theme of roses and one in particular provides a clue to the citation on his epitaph:

Leaning you, the fresh clear

rose, against my closéd eye –

you would think a thousand eyelids

were placed

against my warm lids,

a thousand sleeps against my feigned sleep

in which I wander

through the perfumed labyrinth*

At the end of October, 1926 Rilke wrote a will he sent to Nanny Wunderly. “Puerile, perhaps,” he recognized, but he was afraid that serious illness could make it impossible for him to determine the conditions for his funeral.

“Should I die in Muzot, or anywhere in Switzerland, I do not wish to be buried in Sierre, nor in Miège,” he wrote. “I would prefer to be buried in the hilltop churchyard next to the old church at Raron. Its surrounding wall was one of the first spots from which I received the wind and light of this countryside, together with all the promises which it, with and in Muzot, was later to help me fulfil.”

He wrote in one of his last poems: “I mounted suffering’s tangled, criss-crossed pyre”. If anything, it was an understatement of his suffering. But he told Nanny Wunderly suddenly in those final days: “Never forget, my dear, that life is a thing of splendour. Help me to my death. I do not want the doctors’ death.”

Rilke died in the Clinic Valmont above Lausanne on 29 December 1926 at 3.30 in the morning in the arms of his doctor from a late diagnosed leukemia.

On a bitterly cold 2 January 1927 he was buried in Raron, after a short Catholic service, Bach from the organ and violin by a young protegée. One of his orators quoted from the First Duino Elegy: “They’ve finally no more need of us, the early departed…But we…, could we exist without them?”

* The epitaph in Raron reads:

Rose, oh pure paradox, the joy

of being no one’s sleep despite so

many lids.

The Rilke Foundation website has a page on Rilke’s preferred locations in the Valais. They include the Fynges forest, one of Europe’s last large stands of lowland pine. Rilke wrote:

“Outside is a day of inexhaustible splendour. This valley inhabited by hills – it provides ever-new twists and impulses, as if it were still the movement of creation that energized its changing aspects. We have discovered the forests (Forêt des Finges) — full of small lakes, blue, green, nearly black. What country delivers such detail, painted on such a large canvas? It is like the final movement of a Beethoven symphony.”

***

Peter Hulm is a contributing editor to Global Geneva. He lives part of the year in the Valaisan village of Erschmatt overlooking the Rhone Valley and – almost – within distant sight of Muzot and Raron.

Rilke’s voyages: Europe, North Africa, discovery of the Rhone, and his reflections: Museum auf der Burg, Salle Rilke, Raron: 1 June 2024 onwards — fondationrilke — 7 June 2024 (LINK)