Is 'Under the Skin' the Best British Film or a Divide?

Delve into the cinematic divide provoked by Jonathan Glazer's 'Under the Skin'. This British film intrigues and polarizes audiences, igniting debates on its merit.

Delve into the cinematic divide provoked by Jonathan Glazer's 'Under the Skin'. This British film intrigues and polarizes audiences, igniting debates on its merit.

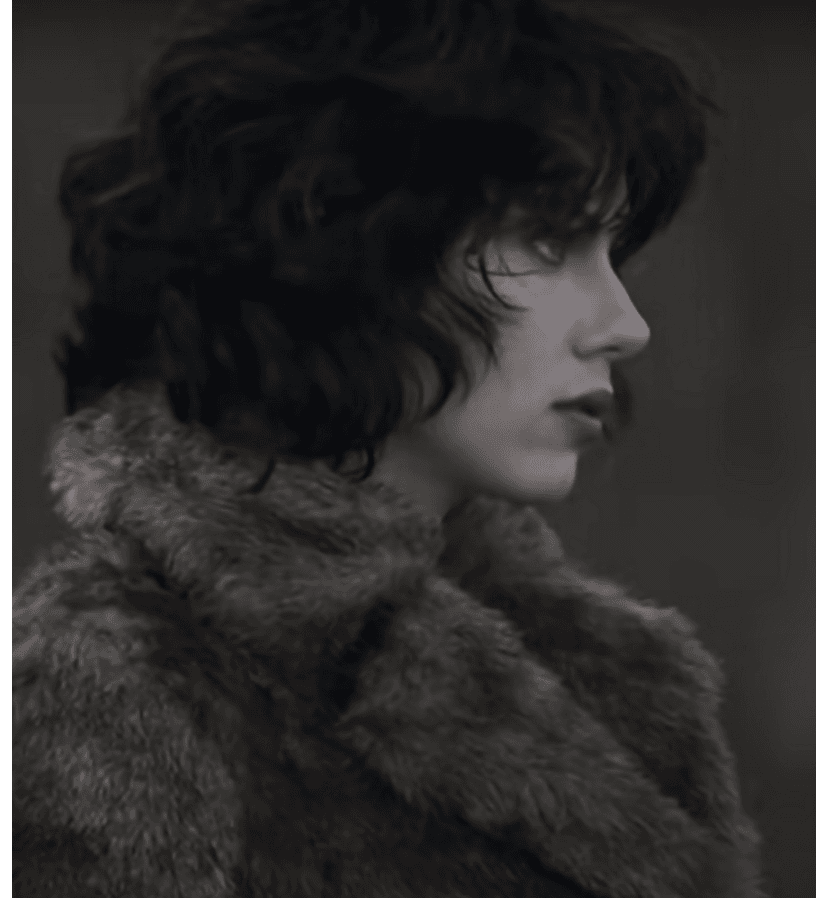

Under the Skin (2013, released in the U.K. in 2014) is about a female alien (Scarlett Johansson) sent to Earth to harvest men for their organs and lands up in Scotland (don’t worry, that’s not a spoiler).

Here’s one woman’s dismissive judgement: “In the real world, real women are raped and killed all the time by actual human men. But we needed a cautionary tale about sexy lady alien serial killers who prey on unsuspecting horny men.”

That was MaryAnn Johanson’s opinion on Under the Skin, which is pretty much completely the work of Jonathan Glazer, director of Sexy Beast and prizewinning video ads, along with Walter Campbell, freely adapted from the 2000 book in English by Dutch-born writer and naturalized Brit Michel Faber.

In the book she and a male partner pretend to be a farming couple, leading some to read the story as a protest against the way we treat animals. Though Faber has apparently rejected this suggestion, the film version has a notable lack of animals onscreen, except for a drowning dog, or on the soundtrack, though she goes in search of birdsong, it seems. And there is a scene of shopping for fake fur.

wikipedia records: “Glazer developed Under the Skin for over a decade. He and Campbell pared it back from an elaborate, special effects-heavy concept to a sparse story focusing on an alien perspective of the human condition. Most of the cast had no acting experience, and many scenes were filmed with hidden cameras.”

“It’s hard to top something with the chilling originality of the top scorer,” MASSIVE Cinema said in a statement. Nicholas Bell of IONCINEMA.com said it was a “cinematic masterpiece that’s surreal, scintillating, and unforgettably strange”. “One of the most singularly mesmerising movie watching experiences I’ve had in a long time,” said Dustin Chang of Floating World. Stephen A. Russell of The New Daily labelled it a “genre oddity of the utmost excellence”.

So it beat This is England, Children of Men, and Ex Machina to the prize.

Why then, do I stick by my 2015 judgement that it doesn’t make sense?

Clare Stewart interviews director Jonathan Glazer and producer James Wilson. 16:08 min.

All the discussions I’ve heard since then confirm that Glazer freely interpreted the book when he found the original story would not film interestingly.

But I also stick by the second half of my assessment: it remains utterly absorbing as you watch — funny, intriguing and disturbing. It also has a gorgeous, eery sound track by the brilliant Mica Levi, who won a European Film award for her contribution late in production when Glazer realized diegetic sound would not work.

You can rent or buy it on Amazon Prime Video or watch it on Britain’s ITVX if you have a premium subscription.

My full-on postmodern take on the film is here. But my quick take at this moment is that Glazer’s ad-supremo experience led him to reverse all he had learned about glitz and messaging for TV advertising in favour of a documentary style and non-explanation of meanings in Under the Skin. Luckily he had Scarlett Johansson to carry him through, because he ended up with 270 hours of film to edit for his 2-hour film.

One result is that some reviewers thought they needed to explain exactly what you see on screen:

It remains perhaps the most polarizing science fiction film of our time. Just look at the imdb user reviews, and the variations between the top score of tens scattered thickly among the 1s (lowest rating). From “a profound study of our society” to “If you fall asleep you will have missed nothing”. Another reaction: “It feels like you spent 5 hours watching an hour long movie. […] The movie is a battle with your buttocks to not get up and do anything else.” (That got 10 thumbs up from supporters.)

As the critic Laura Mulvey has pointed out (in Death 24x a second: stillness and the moving image, 2006) documentary, despite conventional presumptions of easy readability by the spectator, is fundamentally ambiguous: “Any factual raw material arouses, or should arouse, a practical sense of uncertainty in terms of its interpretability” (10-11).

Much like the French film-maker Robert Bresson, Glazer asks you to piece together the introverted story in your mind as you go along, and like Bresson he uses many non-actors in Skin. However, instead of Bresson’s religious concern to demonstrate God’s grace in action, Glazer seems more interested in the humanization of an individual in an equally bleak world.

The strangeness of everyday life begins with the Scottish accents. It was a brilliantly funny idea to have the alien (played by Johansson) encounter raw Scottish vowels in all their complexity. I’m sure most viewers were as lost as she was in their conversations.

But it didn’t matter. The first real dialogue doesn’t occur until 13 minutes into the film and it’s minimal after that.

Johansson herself, though, has an almost impossible task, to play an alien who has learned human language but, in contrast to Jeff Bridges’ character in John Carpenter’s Starman(surely another reference for Glazer), she never learns how to connect with humans.

Why Under the Skin as a title? The book suggests it’s because we are all the same under the skin. But that’s not true in Glazer’s film. Skin Deep would have done just as well. The mysteries remain. The opening seems to be a combination of wormhole travel and creation of a human eye (as some viewers have understood it) while off-camera an alien (Johansson) learns to speak English. But Johansson’s alien, we can see, already has human form and skin. The key question of her skin is skipped at this point and never really resolved. It is also not obvious whether the first woman and the Johansson alien are meant to look alike, though they do vaguely resemble each other, and of course (this is filmland) the clothes fit exactly.

Nor is it clear why the first alien’s body is on a bright white surface, given the surrounding gloom of the countryside, though some viewers might remember The Matrix.

This ambiguity is not cleared up by re-viewing. We see the motorcyclist, credited as The Bad Man, riding the empty roads in the gloom, pulling up just after passing a van, then walking into the dark. He comes out with a woman slumped over his shoulder (one reviewer said he picks her up from the beach but I didn’t see it). He dumps her into the back of the van. We then see Scarlett Johansson undressing the body to don her clothes.

For the visually literate, this tells us (later, if not immediately) that the dead woman is also an alien, that the motorcyclist is another alien who has collected her, and that Johansson will be taking over van duties as The Female.

We are given no explanation of the motorcyclist’s role in Johansson’s life. We therefore presume the character is her ‘minder’ or partner. We never learn why only men are being harvested. In the book, it seems, it is for their muscles, a delicacy on the remote planet. But that hardly disqualifies women.

Where Glazer’s “documentary” strategy works is that as Johansson cruises the streets in her van looking for victims, we too inspect each male passerby for his potential use: too young? too old? too thin? What is she looking for? We never learn. Only that they want to have sex with her.

Flickfilosopher MaryAnn Johanson, who complained of sexism in the story, missed the number of times we are shown Johansson cruising for women (though we are never shown any being caught), and there is a whole section devoted to women being made up in a shopping mall, and Johansson then puts on makeup like a child. It remains a hole in the story. We follow the Johansson alien when (in close-up) she picks out a fake-fur top in a shop, but we see no indication of how she pays for her purchases, or any scene that tells us how she fills up the van with fuel.

The manner in which the men are trapped is inexplicable and rather incredible. Only one man seems to find it odd to be sinking into a black pool of black goo and looks around as he walks across the floor towards Johansson, and asks whether he is dreaming.

One of the victims finds another floating before him in the ‘pool’ and moves a hand to touch him, but we do not know why, or why he does not help himself. The scene is there to show us the other man’s organs being extracted from his skin, for whatever reason we can only guess. It is horrifying in its speed, but leaves us not much wiser about its import. Is this just a gruesome movie rather than a meditation on human behaviour like 2001: A Space Odyssey?

We have no explanation of why the motorcyclist wants to inspect Johansson (if that is what he is doing), and why he stares into her eyes (except in clichéd terms to spot whether she will betray sympathy for humans).

What happens in Glasgow is the opposite: the humans help each other. A pack of strangers (young girls) take The Female clubbing. A Czech tourist tries to save a man struggling in the waves, who is trying to save his wife, who is trying to save a drowning dog. Johansson falls in the street (deliberately? that’s what it looks like) and men help her to her feet (she apparently did the scene six times with non-acting passers-by). On another occasion, she is given a rose by a man handing them out to motorists though his fingers are bleeding from the thorns.

In what many find the most disturbing scene of a Czech tourist she kills on the beach, the centre of the most dramatic and the only non-sexual incident, we do not learn whether he was harvested or not? If not, why not, given their previous conversation explicitly telling us he was alone?

When she picks up a man with neurofibrosis (Adam Pearson), The Female takes the decisive step of allowing him to escape, we presume because she learns of his social isolation from others. But after running naked across the fields in cold November weather, the neurofibrosis sufferer is taken prisoner again by the motorcyclist when climbing through a fence. We do not learn how the male alien knew where to find him, or for sure that he was captured.

The Female runs away (from her job) and in a lochside restaurant tries some cake (we are not told why), and coughs it up. Moral: she is still not a human. But we can draw no conclusion from this, even if we get the message.

She then gets on a bus, and a passenger takes her home and feeds her dinner (or at least shops for it, but there is no dialogue). They watch Tommy Cooper on television doing one of his nonsense skits in a fez (a good touch), and they start to make love.

Shocked to discover how her human body is made (it is not clear what her problem is), she runs into the woods, encounters a logger and then sleeps in a stone hut. She wakes up to find the man caressing her leg. She runs away, and he pursues her, leading to her death when he douses her with gasoline and sets it alight when he sees her trying to remove her human skin.

But would so little fuel cause so big a conflagration? It didn’t make sense at the time and on reflection reeks of Hollywood, where all fires are impressive.

At least it gives us the film’s most ‘beautiful’ scene, when the motorcyclist stands on the top of a mountain searching for The Female in a scene reminiscent to some viewers of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, though in fact it is closer in staging to Benedict Cumberbatch’s scene in the TV series Sherlock. Good film-makers know the preferences of their audience.

But since we have been primed to watch the film closely for clues to its meaning, we are likely to wonder how The Bad Man seems to have lost all his alien GPS powers.

As for Johansson’s alien form, it looks very much like her own, just a different colour. What a disappointment.

Against the blatant ’emotionality’ of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws — “merely a variation on the standard Universal monster movie, albeit an excellent one” (according to one critic) — Skin exemplifies emotional control and lack of sentimentality.

We still have to account for the fascination that Under the Skin exercises over a part of its audience, and the equally virulent rejection by others.

Like a child, the Johansson alien learns of adults’ tastes for disgusting food (the Forêt Noire cake) and experiences (perhaps) the responsiveness or simple discovery of her sexual organs. Johansson, of course, has an almost perfect juvenile face and wanders through the film environment like a detached child. If the motorcyclist is the demanding father (and he does treat her as if he is an authority figure), her capturing of the young men could function symbolically as the elimination of rival siblings (a common feeling among only children, it seems).

The opening birth-scene is followed by the recuperation of the dead alien and the reclaiming of the woman’s effects by Johansson. It is possible, taking a psychoanalytical view, to see this scene as the actualization of the common childhood belief that they have replaced a potential sibling who died, but the narrative is ambiguous enough to leave that open, and only in hindsight can we deduce that the other woman is also an alien.

Skin leaves us to work out the meaning of the contrast between the beginning and the end. What is the difference between the death of the first woman alien we see and the Scarlett Johansson figure? Does the death by burning indicate that the motorcyclist no longer has a partner?

Some viewers have suggested the narrative arc shows us the obvious message that The Female is coming to sympathize with/appreciate humans and is killed for it. But there’s nothing to indicate that either way. The scenes at the loch in the tea room and on the bus do not lead her to show any more humanity than before, or to respond better to human interaction (think back to the beach scene). And the scenes with Adam Pearson (if we are to take anything from the book) suggest The Female spares him because his physical form is closer to her alien body in the novel (though not as we see it in the film).

Questions to which you will have to find your own answers.

My postmodern theorizing (LINK)

International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, 25 November 2024 (LINK)

swissinfo. Swiss government adopts three-pronged approach to end violence against women. 25 November 2024 (LINK)

UN Women. 140 women are murdered every day by relatives. 25 November 2024 (LINK)

Mona Ali Khalil. In Sudan, Some Women and Girls Are Choosing Suicide to Avoid Rape. PassBlue, 25 November 2024 (LINK)

U.N.: 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence. 25 November – 10 December 2024 (Human Rights Day) (LINK)