Understanding the Biden-Trump Afghanistan Crisis

This article delves into the Afghanistan crisis under Biden and Trump. It analyzes US foreign policy failures and the humanitarian impact on Afghans, urging a shift in approach.

This article delves into the Afghanistan crisis under Biden and Trump. It analyzes US foreign policy failures and the humanitarian impact on Afghans, urging a shift in approach.

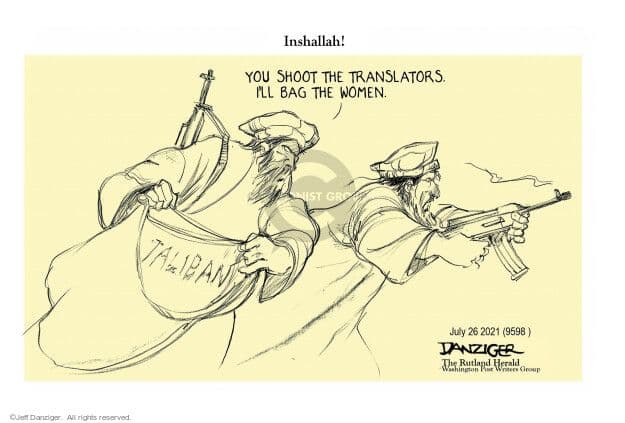

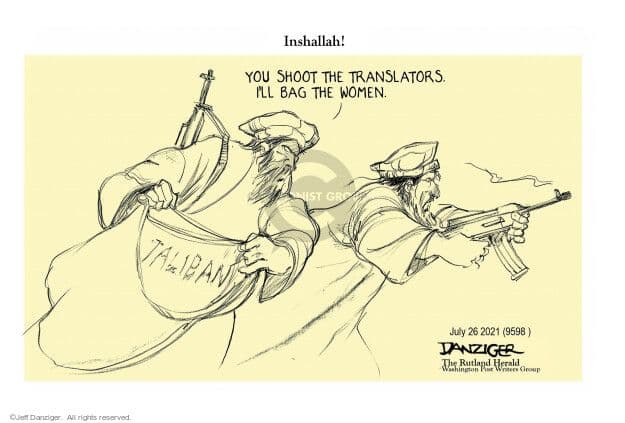

All cartoons by Global Insights contributing editor, political cartoonist and author Jeff Danziger.

President Biden, who had opposed long-term U.S. military engagement from the very beginning, may be wishing that Afghanistan simply go away. But it won’t. People, including concerned vets on both sides of the political divide, keep asking about it. They still find incomprehensible why the US simply abandoned its friends. As with Trump, Biden has often embraced a dismissive if not arrogant attitude by declaring that Afghanistan cannot be helped.

Certainly, Afghanistan may often come across as hopeless. And without doubt, Afghans, particularly those engaged with massive corruption under the western-backed Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani regimes, must assume partial responsibility for the current debacle. But so must the U.S. Failing to learn from history since the Coalition invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, Washington relied far too much on the military for solutions. It also pursued policies which sought to ‘fix’ recovery too quickly and without due diligence. This enabled the oft uncontrolled abuse of taxpayer resources by both American and Afghan contractors, some of whom made fortunes.

For anyone who knows Afghanistan, Biden could have at least tried to clean up Trump’s mess by postponing U.S. withdrawal until the next fighting season, notably the spring of 2022. Given that combat on all sides has always tended to abate during the harsh winter months, this could have lent him precious time for an attempt to renegotiate the peace process. Under Trump, the treaty was shamefully one-sided, basically handing the keys to Kabul to the Taliban.

Biden had the opportunity to push for a more inclusive agreement by ensuring that no one, whether the country’s minorities or Afghan women in general, were sold down the river. Yet, the president refused to explore other potentially viable options, as some of his aides were urging, such as the formation of an internationally supervised non-political interim administration representing all of Afghanistan’s ethnic and tribal groups.(See Global Insights article by Peter Jouvenal and Edward Girardet)

To later claim success by airlifting nearly 130,000 Afghans out of Kabul is like an arsonist taking credit for saving people from the fire he himself started even if – in this case – the initial igniting must lie squarely with Trump. But his two presidential predecessors, Bush and Obama, also helped enable America’s misguided engagement with Afghanistan.

The result is that Afghanistan is now facing an ignobly disastrous humanitarian and economic situation. As David Miliband, President of the New York-based International Rescue Committee, recently maintained in a CNN editorial, Biden had argued that the pull-out would not signal the end of American support to the Afghan people. The U.S., the president had pledged, would provide active humanitarian support and diplomatic engagement. But this has not happened, Miliband argues. Instead, the policies of the US and other Western powers have done quite the opposite by “delivering isolation, economic mayhem and human misery.”

Over the past weeks, much of the international humanitarian and development community, some of whom have been engaged with Afghanistan since the beginning of the 1980s, have been urging both the United States and Europe to rescind their sanctions against the Taliban. This is not because they want the West to recognize an abhorrent regime that grabbed power at the end of a gun. It’s a matter of saving ordinary Afghans. This is what the Oslo talks earlier this week between high level French, British and other western representatives, including NGOs, and the Taliban were negotiating.

Aid coordinators are warning that unless Washington lifts its financial constraints, they will not be able to help the overwhelming majority of Afghans, many of whom are facing outright starvation. An estimated 10 billion dollars, initially slated for the previous Ghani regime, are being currently withheld from the Taliban. “We cannot save lives without lifting the sanctions,” maintained Jan Egeland, head of the Norwegian Refugee Council, which took part in the talks. “They are harming the same people that NATO spending billions of dollars were defending until August.”

While some critics maintain that the international community should have no dealings with the Taliban, both Egeland and others say that the West has little choice given that ordinary Afghans, such as teachers, doctors, and nurses, are not receiving salaries. The same goes for most other livelihoods. The entire country is in survival mode.

What this means, said Egeland, is that “we are being held back as much by the sanctions as by the Taliban’s wage-related problems.” As some observers have also noted, even if the European Union wished to engage on its own with the Taliban, U.S. law prevents European, including Swiss, banks from sending funds to Afghanistan. “No bank is going to take that risk,” said one EU diplomat. Even if NGOs have funds to disperse, they are confronting all sorts of hoops and hurdles to get them into the country.

With growing criticism both in the United States and across the globe of Washington’s hard-line approach toward the Taliban, the challenge now is how to convince the Biden administration to change its mind.

One of Washington’s biggest problems is that it has never really understood Afghanistan.

The United States first became militarily involved in this well over 40-year-long conflict in July 1979, when the Central Intelligence Agency began supporting the newly emerging anti-communist mujahideen, or Islamic warriors, following the alleged murder by the KGB of American ambassador Adolph Dubs in Kabul. (See Global Insights article on ‘Murder in Room 117’ by Arthur Kent) This then spiralled into major military and financial backing for the Afghan resistance, largely manipulated by Pakistan’s powerful military InterServices Intelligence agency (ISI) in favour of Pushtun fundamentalists, during the nearly decade-long Soviet war of the 1980s.

This caused the bulk of Washington’s backing to go to Pakistani-sponsored Islamic extremists, some of whom went on to create the Taliban and the Haqqani Network, the latter a US-designated terrorist organization. In other words, the US helped create the very ‘monsters’ that later came back to haunt the NATO occupation. Today, ISI continues to play a double game despite repeated denials by Islamabad. Nevertheless, Pakistan, often referred to as “the other country,” could still prove a useful mediator for tempering the Taliban as part of any new compromise with the West.

While some experienced U.S. diplomats and aid coordinators have always shown an astute knowledge of this Central Asia country and its people, many American politicians have not.

Policymakers have always preferred rapidly implemented approaches, some of which inevitably led to disaster. Following the Red Army departure in early 1989, for example, Washington dropped Afghanistan like a hot potato. This led to brutal civil war during the early 1990s resulting in the deaths of up to 50,000 Afghans but also opened the door to the first takeover of Kabul by the Taliban in 1996.

With the collapse of the Taliban, the Western donors at the December 2001 Bonn Conference immediately sought to impose a ‘new’ Afghanistan supposedly based on western values, such as democracy and equal rights for women, but also a highly centralised government which did not particularly suit the country’s diverse tribal and ethnic makeup. They also did not listen to the well-worn advice of a broad spectrum of international and Afghan aid workers, diplomats, journalists, and analysts with decades of experience with the region.

Some of these stressed that any successful recovery must be part of a long-term approach, perhaps even 30 to 40 years. There are no quick fixes to Afghanistan, they said. Nor should the West throw money at the system. What the country needed more than anything else, they said, was intelligent aid and investment rather than billions of dollars squandered on questionable initiatives.

Equally crucial, as the British, the Soviets and Afghans themselves had learned over the past 150-odd years, there are no military solutions to Afghanistan. The military, Afghan hands have stressed, should not be allowed to run the show, but which is precisely what happened. Nor should there be so much reliance on private military contractors, or mercenaries, many of them unaccountable.

Furthermore, to demonstrate real change, they warned, the ‘new’ Afghanistan should not be a ‘reversioned’ form of the past. Given that many Afghans were fed up if not afraid of the previous mujahed warlords, some of whom committed horrific human rights abuses, the Americans decided to bring them back into the fold, losing the confidence of numerous Afghans.

Finally, as some, such as the Swedish Committee for Afghanistan or Médecins sans Frontières suggested, the Allies should not shut out the Taliban. Whether one liked it or not, they legitimately represented a significant portion of the mainly Pushtun population in the east and south of the country, plus various parts of the north and west. For recovery to succeed, the Taliban had to become part of any future peace solution. This was not done and the militants, who had simply melted into the countryside and across the border into Pakistan when NATO took over, began making their comeback from 2003 onwards.

Overall, much was achieved over the past nearly two decades of western commitment in the form of health, education, and economic development. Yet the West’s Vietnam-style pullout means that the spending of more than two trillion dollars’ worth of military and development assistance by the US and its Allies (over 3 billion by the European Union alone) is proving to be for nought. So, sadly, has been the loss of lives, both western and Afghan, of the NATO commitment, not to speak of the tens of thousands of wounded. With Afghanistan now facing utter destitution, it is increasingly as if the international community were never there.

As informed observers are all too aware, the Taliban are a fractured and largely uneducated movement consisting of different factions. In many ways, they are not unlike the earlier mujahideen with some groups bitterly opposed to each other. While the Talib leadership is seeking to present a unified stand, at least from Kabul, as part of their image to the rest of the world, they have little experience with how to administer the country. A brain drain of highly competent Afghans have already left or are in hiding, leaving few competent individuals to run the show.

Yet, Afghanistan’s new Realpolitik dictates that some form of agreement between the West and the Taliban must be made, even if the Islamic militants are boasting that the Oslo talks have demonstrated international recognition of their regime. While this is not the case from the western point of view, international aid representatives are proposing that foreign support in the form of funds for salaries, food and health care only be made available through the United Nations and NGOs. But this needs to be done now.

As the same time, they point out, humanitarian aid alone is no substitute for a collapsed economy. While emergency stopgap measures are urgently needed, the country itself needs help. Nevertheless, the West should still insist that any form of official recognition cannot happen unless the Taliban agree to minimal but significant reforms, such as primary, secondary and college education for both boys and girls, the right to work for women, a halt to human rights abuses, freedom of the press, and an agreement to eventual free and fair elections under UN auspices.

Diplomats have already said that teachers’ salaries could come from the World Bank-administered Afghan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), but would only be made available to provinces where girls of all ages have been allowed back to school. Worth over 2 billion dollars, this represents the largest single source of aid to Afghanistan prior to the Talib takeover last August.

“The freezing of Afghan assets is, in effect, the continuation of war by other means,” said Norah Niland, who has previously worked in human rights in Afghanistan and is co-founder of the Geneva-based United Against Inhumanity. “Afghan citizens are made to suffer and starve, but are not responsible for the arrival of the Taliban. Indeed, many would argue that it is the policies of the past two decades that propped up predatory governance and widespread corruption that gave the Taliban momentum in their march to Kabul.”

It is highly probable that the Taliban – as they did during their first reign in the 1990s – will seek to pressure aid groups to pay them off for ‘security’ and other ‘services.’ The fear amongst the Taliban leadership is that they will lose support if they cannot pay their fighters, even if considerable revenue is coming through narcotics trafficking and import-export duties. (See Global Insights on Afghanistan as a Super Narco state) Another concern is that they will lose control over armed ‘Talib’ groups who will seek their own forms of sustenance through banditry against the civilian population.

The reality, however, is that times have changed since the Taliban first took the Afghan capital in November 1996, when it barely had one million inhabitants. Today, the city has over five million. Furthermore, 60 per cent of the country is under the age 25, many of whom are literate or at least mobile phone savvy. There are also protests by courageous women against Talib rule which was almost unheard of before.

It is more than likely that armed resistance from non-Pushtun areas will start to grow in the spring, particularly given that initial peace initiatives with the Taliban by Ahmad Massoud, the son of renowned guerrilla leader Ahmed Shah Massoud, who was assassinated by Al Qaeda on 9 September 2001, have failed to produce results. According to unconfirmed reports, the Panjshiris supported by Shia minority Hazaras and other neighbouring groups have been killing and wounding up to 15 Taliban a day.

Resentment is also growing amongst Tadjiks and Uzbeks in the north and west where the primarily Pushtun Taliban are in a minority. The Taliban are reportedly nervous about this and have been arresting people, including westerners, in Kabul believed to be affiliated with the resistance or engaged in other suspected ‘subversive’ activities. “If anyone thinks that this war is over, well, what can I say?” said one British humanitarian coordinator. “In the meantime, it’s our obligation to help the people of Afghanistan survive.”

Edward Girardet is a foreign correspondent, author and editor of the Geneva-based Global Insights Magazine. He has covered wars and humanitarian crises worldwide for The Christian Science Monitor, US News and World Report and the PBS Newshour. His books include: “Afghanistan: The Soviet War”; “Killing the Cranes – A reporter’s journey through three decades of war in Afghanistan”; “The Essential Field Guide to Afghanistan”. (4 fully-revised editions) and “Somalia, Rwanda and Beyond.”

Focus on Afghanistan: Whose responsibility?

Focus on Afghanistan: The Slack platform on evacuation

Focus on Afghanistan: Why and What Next?

Focus on Afghanistan: Will Afghanistan Emerge as a Narco Superstate?

Focus on Afghanistan: The “Tali-Bans’ of the past: waiting for the new decrees.

Focus on Afghanistan: Terror attacks and the guilt of leaving.

Focus on Afghanistan: The country’s ‘Businesswoman of the Year’ escapes from Kabul.

Focus on Afghanistan: What did you expect?

Focus on Afghanistan: The West’s abandonment of Afghanistan: A story of arrogance, ineptitude, and little understanding