Cultivating Media Literacy: Combatting Fake News for Kids

This article discusses the urgent need to educate children on identifying fake news and promoting media literacy, emphasizing a return to quality journalism in schools.

This article discusses the urgent need to educate children on identifying fake news and promoting media literacy, emphasizing a return to quality journalism in schools.

We need to teach our kids to become discerning on the internet in order to detect what is false or propaganda. One way of doing this, writes Global Geneva editor Edward Girardet, is to bring credible journalism back to schools.

While at school in England, I was lucky enough to have a teacher who was an exceptional individual and marked me for the rest of my life. Ernie Polack was a British Jew who dedicated his life to teaching and to fighting injustice, whether apartheid in South Africa or human rights abuses elsewhere. He was also a house master at Clifton College in Bristol, the head of Polack’s House, where Jewish pupils could live and worship. As a teacher, however, he always sought to make sure that everyone respected other people’s religion and views. He also taught us to question words and not to believe everything we read.

Ernie Polack taught a sixth-form (final year) class called “Two Cheers for Democracy” inspired by E.M. Forster’s collection of essays of the same name. For me, this once-a-week, two-hour gathering was perhaps the most inspiring I have ever taken. It is also an approach that should be included in every school system today. If we wish our children to grasp the true power of information in all its forms – words, images, sound or any other format – then they have to learn how to discern what is credible and what is not.

Every week, two of us would make a presentation to the class on how different newspapers and magazine in Europe covered the same issue. We did this based on our languages, such as collecting articles in the German, French, Belgian and Spanish press, and then comparing them with their British counterparts or the International Herald Tribune. Sometimes the perceptions were shockingly different. Not only might France’s Le Monde, Germany’s Die Zeit, Belgium’s Le Soir and Spain’s El Pais produce different facts, but also different interpretations and analysis depending on the country and political slant. The same went for The Times of London, The Guardian, Daily Express, Daily Mail, The Telegraph and The Economist.

Ernie Polack’s point was to demonstrate that every society, every political or religious tendency and persuasion, can engender different perceptions of the same issue, such as the role of NATO, the European Economic Community – as it was called in those days – or oil interests in the Middle East. He encouraged us to question the facts and to determine whether one report was more accurate or trustworthy than the other. Even more adamantly, he wanted us to grasp the importance of multiple information sources and to know how journalists obtained their information and whether we should provide them with our trust. “Never necessarily believe what is written,” he would say repeatedly. “Always question.” And then he would add: “Maybe there is no one truth, but many.”

Despite the plethora of internet information in the 21st century, it was perhaps much easier in those days for a young person to put together a relatively clear picture of what was happening in the world than today. Editors served as gatekeepers of the information their reporters provided. The newspapers acted as ‘discovery packs’, whereby the reader never quite knew what to expect, but might read an article on birds of the tundra or why Europe’s steel industry was collapsing because it was well-written and caught one’s attention. Nowadays, these are articles that one might never see if one only relies on social media for information because it may not be part of our ‘online’ profiles. So it was up to the reader to decide whether one should read a particular publication, or not, or whether one should also seek access to other information sources, such as radio, television and other newspapers and magazines.

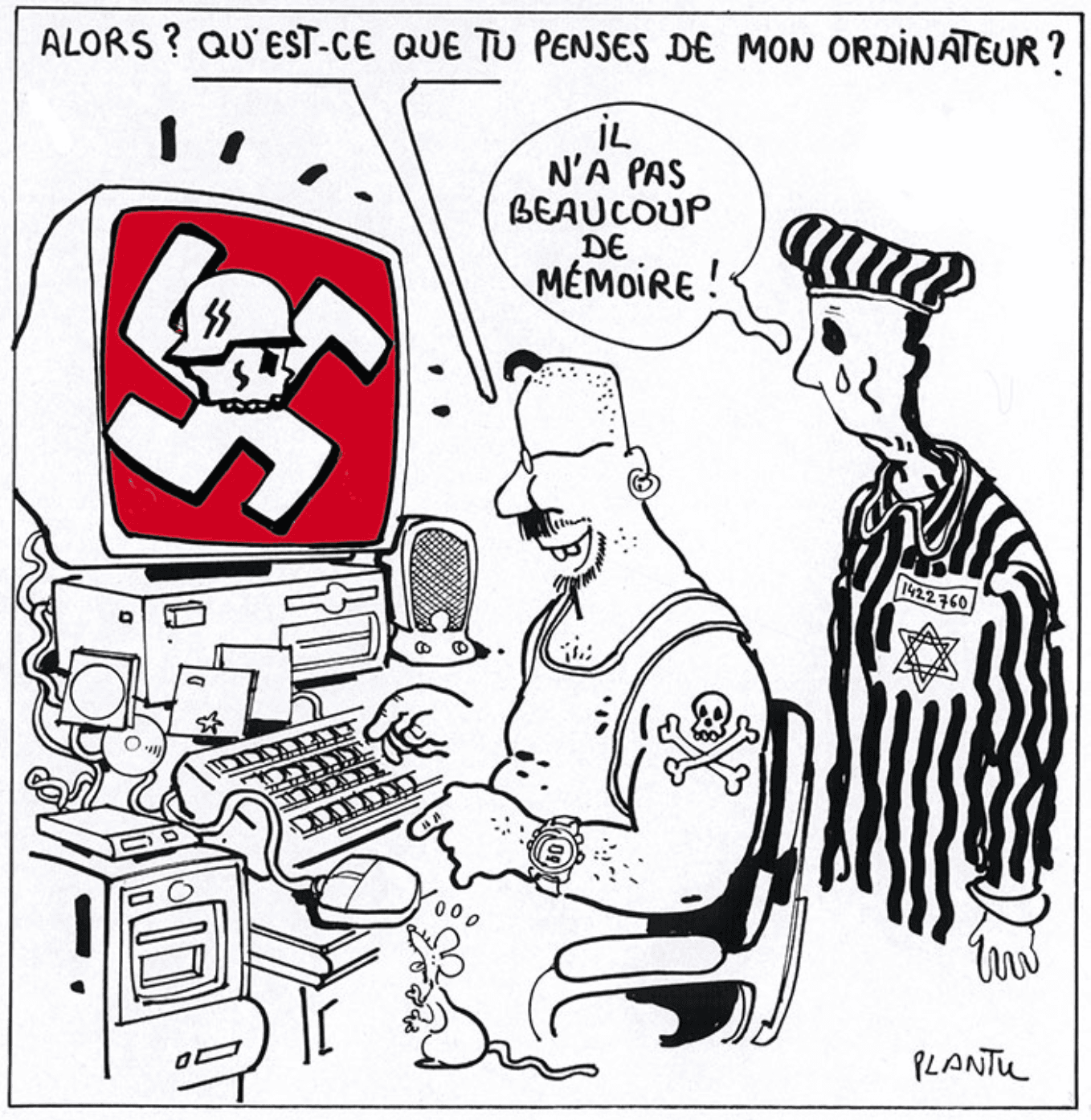

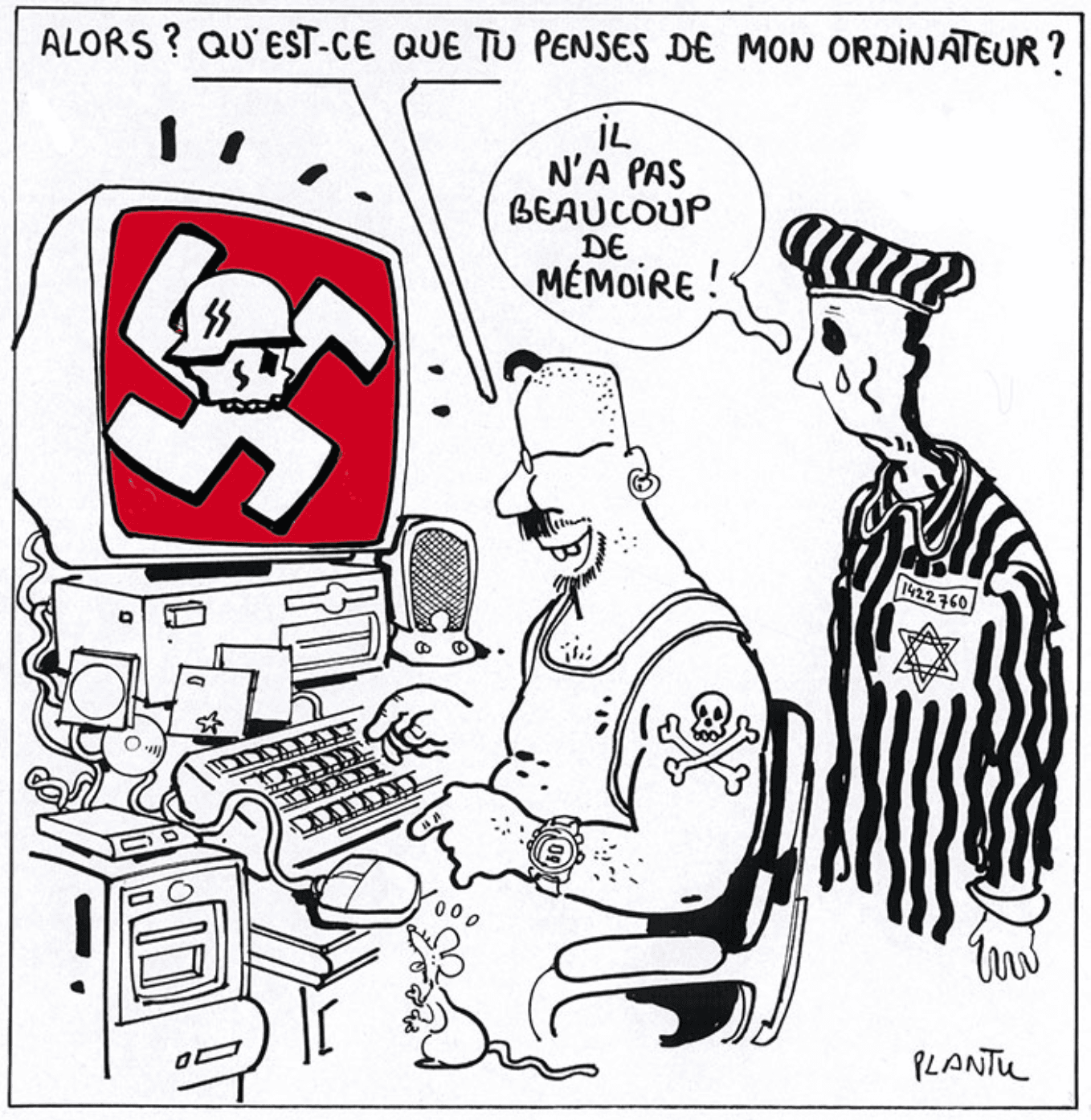

Nowadays, many young people, including my 16-year-old son, tend to seek their information on the internet and social media, such as Facebook or YouTube. Much of what they see or read is questionable. After all, if it’s online and it looks good, it’s got to be true. Furthermore, they (and this goes for those adults who rely primarily on social media for their information) now tend only to be exposed to silo ‘infosources’ shared with them by like-minded souls in the form of links, videos and blogs. What distresses concerned parents and teachers is the amount of propaganda, untruths and fake news that masquerades as credible content. As The Guardian points out, such manipulation can even succeed in turning nasty pieces of work such as Hitler into nice guys.

This base reality was also accentuated by a November 2016 report by Stanford University on how teenagers in the United States today perceive what they read online. The report bleakly concluded that large portions – as much as 80 or 90 per cent – of the 7,800 teenagers surveyed could not differentiate fake from real news or sponsored ads from news articles. As a father, but also a journalist who knows only too well the undermining impact of rumour and false information, sometimes leading to disastrous wars and humanitarian crises, this is an unacceptable situation. How can we have allowed our children – the new generation – to be so utterly misinformed in the age of communications, not just in America but worldwide?

Of course, the deterioration of credible information does not stop there. People on both sides of Brexit used lies and mistruths to put their arguments across and gullible consumers went for it. The bulk of the media, including the BBC, completely failed in their job to report properly, often by not calling out the politicians on their lies or because so many people now feel that they can do without credible journalism or are unwilling to pay for it. (Both in the UK and the United States after the elections, however, newspaper sales and subscriptions immediately rose after the results became clear).

The end result is that the UK’s referendum proved to be thoroughly uninformed, making concerned citizens question the validity of British democracy. The same thing has crept into public debates with the rise of the Right cashing in on popular discontent in Germany, Netherlands, France and Austria. At least in Switzerland, where the cantons and federal government hold referenda every three months on issues ranging from immigration quotas to how many wind mills should be constructed, the ballots provide relatively clear summaries representing different arguments for those who have not bothered to inform themselves on their own.

Educators professed shock some years back when former US President George W. Bush spoke as an alumnus at Yale University making the point that even a ‘C’ student can become leader of the Free World. In essence, he was saying that you don’t really have to take your studies seriously; you can still make it as president. Trump took it further by demonstrating that lying or throwing out untruths will eventually make them real. This is precisely what ISIS, Boko Haram and other insurgent or terrorist groups have done in their bid to rally impressionable young people behind the black flag or to die for completely nebulous and terrifying causes.

Claims by Facebook, Twitter and other social media that fake news can be cleansed may succeed in filtering some content. But then it becomes a question of whose truths? Vigilance can quickly turn into censorship and information control, including supposedly innocuous day-to-day actions. (Such ‘oversight’ recently prevented a journalist from being paid for an article on North Africa because the clearing bank had picked up the word ‘Libya’ and barred the transfer). Simply blocking information because computers pick up specific words or phrases will not ensure credibility.

Basic democracy depends on society’s ability to help our kids navigate the internet with its billowing clouds of untrustworthy, manipulative or outright false content. We need to teach them to be more discerning about what is credible and what is not. Just because they read it online in a visually impressive statement or a slick video by a well-known pop star or politician seemingly highlighting all the right issues does not mean that it is real.

Recalling Ernie Polack, the only way is to provide them with the tools of knowledge and perception that will enable them to question whatever they see or read. And to determine what is real and what is fake. This is where a return to quality journalism based on nitty-gritty, on-the-ground reporting can make a profound difference. High school education needs to include Ernie Polack-style classes as part of their basic learning.

For their part, newspapers and magazines willing to invest in quality journalism need to become far more involved in the education of our children. Young people need to learn how to read again and to understand that true reporting is not simply throwing up content onto the internet and calling it news. Regardless whether in print or online, credible media need to be incorporated into their learning as a social responsibility. But this means allowing independent media to regain trusted ‘gatekeeper’ roles. It also means supporting journalists with the means to provide the sort of reporting, insight and analysis that will enable young people – and adults – to make informed decisions about their lives and what is happening in the world.

Edward Girardet, a former foreign correspondent, is editor of Global Geneva magazine.